A small moment in Alan Berliner’s new film First Cousin Once Removed, which makes its HBO premiere on Monday night, shows an adult man visiting his Alzheimer’s-stricken father. The last time the two saw each other in good health was a painful parting several years prior, but the son now smiles gently and says, “It’s been some time.” The moment resonates with context. We have previously been told that Jeremy, the son, was never good enough for his father, Edwin Honig, a great poet and university professor and an extremely demanding—even cruel—parent. But time can heal such wounds.

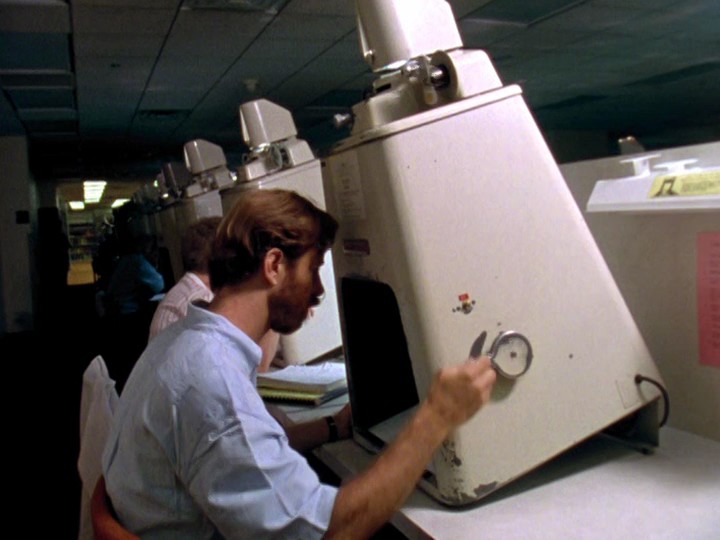

Jeremy only plays a small role in First Cousin. The film’s primary focus is Edwin, who is related to Berliner as per the film’s title in addition to being the much younger filmmaker’s lifelong friend. The film operates as a documentary portrait in which present-day exchanges between an offscreen Berliner and an in-and-out-of-his-wits Edwin lead the younger man deep into investigating his elder’s past. Edwin’s history is related to the viewer through archive film images and photographs and testimony from loved ones, all assembled puzzle-piece style to form a chronological sequence, as though we are bearing witness to the ongoing creation of a life’s story. Like Berliner’s previous films, First Cousin is a work of great compassion for people, which entails striving to understand their flaws and weaknesses as well as their strengths. The films collectively suggest that the best way to understand someone is to gather a picture of his or her entire life, and then find your own within it.

From early on in his film career, Berliner’s works have seen particular, individual stories as universal and vice-versa. The New York-born filmmaker of European Jewish descent’s early The Family Album (1986) represents a life in composite by weaving together scenes from a large number of American home movies shot between the 1920s and 1950s. The film moves from childhood through to adulthood by shifting from one previously anonymous person to another. Each life onscreen—presented without the context of name, place, or date—could essentially belong to any of the film’s viewers; Berliner then emphasizes and personalizes this point by including the voices of his own family members talking on the soundtrack in accompaniment to the images.

The director’s relatives include Oscar Berliner, his ornery father who, despite protesting that average lives don’t belong in a movie, took home movies of his own children when everyone was younger. Oscar is the evasive object of attention in Berliner’s portrait film Nobody’s Business (1996), with his continual dismissal of his son’s efforts to interview him about his life (after all, he says, “Who the hell am I?”) writ large through grainy footage of two boxers sparring. Oscar also appears briefly in Berliner’s two other portrait films—Intimate Stranger (1991), about Berliner’s oft-absent grandfather Joseph Cassutto, and First Cousin. All three films contain the same structure of a life presented in fragments as a solution to the same essential problem: Oscar’s stubborn refusals to answer questions, like Joseph’s constant work trips and Edwin Honig’s frequent mental absences, makes it difficult to get to know them.

This problem raises the question of whether and why the distance from these men should be bridged—or in other words, to paraphrase Oscar, who cares? Alan Berliner begins Nobody’s Business by claiming that people can learn from Oscar’s story, and in time reveals that he is seeking to learn about himself through it. The filmmaker’s portraits of other people carry with them the lingering, sometimes uncomfortable air of autobiography. In this case, Oscar says that he offered himself to his two children—Alan and his sister Lynn—as a role model, which could mean that Alan inherited a body type, intelligence, critical thinking, and solitude. Alan tells his father that, like the overwhelmingly self-isolated parent—whose most extended daily conversations unfold with his building’s doormen—he is coming to spend more and more time alone. When Alan asks Oscar, “What do you see of yourself in me?” the question carries both curiosity and concern.

“He’s a Berliner. He doesn’t extend himself,” Alan’s sister Lynn says of Oscar, immediately raising the possibility of this being true of Alan. The unanswered, unresolved and universal question of to what extent our fates are determined by our elders carries over into First Cousin, as Alan sees himself in Edwin’s story. Edwin’s son Jeremy tells Alan that Edwin always preferred the filmmaker to his own children, to which Alan immediately apologizes. (Jeremy replies, “It’s OK. Its in its compartment”—time has healed this wound, too.) The moment recalls something said by one of Joseph Cassutto’s children in Intimate Stranger—“I would have loved to have been his friend instead of his son, because I think that he would have done anything for a friend.”

These moments together haunt First Cousin’s early, brief scenes of Berliner playing with his own young son, Eli, for the camera, home movie-style. The contrasts can easily lead viewers to speculate about the possibilities for the kind of parent that Alan is and could become. Furthermore, they make it hard not to think that we learn from our role models in the negative as well as in the positive, understanding who we are and want to be in relation to their trials and errors.

Berliner’s assemblages of the fragments of other people’s lives offer the impression that, though aspects of a person can change over time, his or her innermost self remains consistent. First Cousin suggests that for as long as we stay open to people, they can continue to teach us, and we can continue to learn from them. Alan tells Edwin at one point that he believes the older man never stopped being a teacher, which means sharing lessons and histories as well as leaving space for others to create their own. Some of Edwin’s former students that the professor would often stay silent in class, allowing them to lead discussion; the mind that Edwin has now leads him to tell Alan to “Make up songs and memories and tell them to your grandchildren,” and to tell Eli, “Little boy, I like you. Take me for a ride in your story.”