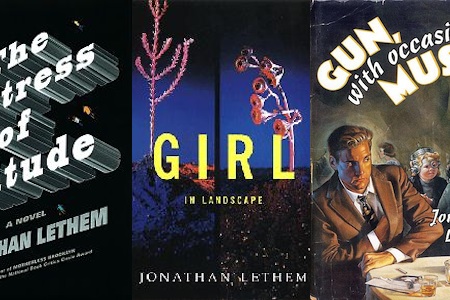

Celebrated author, noted essayist, MacArthur “genius” and champion of a handful of underappreciated artists (most predominantly among them, Philip K. Dick): Jonathan Lethem has covered a considerable amount of territory since his first novel, Gun, with Occasional Music, was published in the mid-1990s. In the process, he has become one of the most consistently compelling writers working in the world, responsible for a handful of the best novels completed in the last two decades. Fandor co-founder Jonathan Marlow interrupted Lethem while he was in the midst of writing his latest novel, the forthcoming Dissident Gardens.

Jonathan Marlow: Admittedly, the only interviews that are of much interest are those in which the subject strays from their prepared statements, forced from their areas of comfort.

Jonathan Lethem: It is a truism for me that when I meet another writer, no matter how much mutual admiration and real interest there may be, the conversation is stillborn until we switch to some subject that has nothing to do with writing. When we get on to baseball teams or a movie or what we were doing earlier that day, then you can actually have a conversation. It is just getting away from what you know. The problem with writers talking about writing (their own books, especially) is that you’ve gotten them in their craftsman, professional footing. That is actually not how any of us got interested in all this stuff to begin with. We all were these amazed, stupefied, exhilarated readers who fell in love with mysterious operations. With not knowing how narrative works or not knowing why fiction was compelling to us but just being electrified by what it was doing. Then, in a necessary, tragic fall, we all meticulously became dull students of this magic and learned how to produce it and tinker with it and improve it and labor at it. So we end up suffocating the magic out of it in order to be magicians. If you get people talking about, ‘Here’s how I did this research that’s all behind the scenes of this material that I hope flows so effortlessly under your attention and here were the boring hours I spent correcting sentences and understanding the mechanics of my own plot or grasping what I was on about with introducing such‑and‑such characters…’ That is really exhausting. We think we want a lot of that talk and it’s actually really innervating.

Marlow: In an interview with the Rumpus you mentioned that films were nourishing for your writing.

Lethem: One of the reasons is that I don’t make film. I’m still predisposed to be in that wondering, passive, marvelous, fan‑ish relation to it, where I just let it suffuse me. Even though I think about it pretty articulately and it’s a pretty close cousin to making narrative fiction, I don’t have that horrible, grinding, professional footing when I’m talking about or thinking about film. Especially when I’m watching it. I’m able to reconnect with the part of me that just has this amazed narrative appetite, where I just want to gobble up more stuff and be surprised and be the recipient of the magic. So it satisfies my need to be awash in narrative stuff—characters and situations and digressions—and [have] my own expectations rewarded or my own expectations delightfully thwarted instead. All of those things… without having to think about the mechanics of sentences and paragraphs and plots and words on a page. Without getting stuck in my own tendentious, professional awareness.

Marlow: There tends to be this inclination among critics and writers (whether it is film critics or writers on literature) to create certain taxonomies. Something that is attractive in your writing is the freedom to allow genres to intersect. That goes, of course, all the way back to your first novel, Gun, with Occasional Music, where you’re very open to the idea that these two very well‑defined genres can collide and something unique can come from that.

Lethem: Absolutely. It’s perverse. My interest in freedom from the constrictions of genre was, at its outset, an extremely hidebound and literal interest. I identified extremely, well‑articulated genres and mated them very specifically. A hardboiled detective story is almost as precise as a sonnet in its performance of rhythm and expectation. The dystopian science fiction novel (as I’d come to understand it through [George] Orwell and [J.G.] Ballard and Philip K. Dick) was not much looser. Certainly, they were genres that, if you made reference to them, people had extremely specific points of contact. I excluded other experiments. I tried to make a very pure and almost scientific mating of these two things. Eventually, my interest in freedom from the constrictions of genre migrated in a direction of a much deeper, polymorphous shrugging off of even thinking about them. I am no longer conducting some diligent, literal experiment in reconciling two pure and clearly articulated forms. Instead, I am just mucking around and letting those points of contact with certain formal expectations—essay, fiction, whatever it might be—arise and become my plaything when it interests me. I used to think that I had a responsibility for violating genre. That was more responsibility than I wish to recognize any longer. [Laughs.]

Marlow: It becomes an albatross, in a way.

Lethem: Yes. These days, it’s its own genre.

Marlow: Whereas the current book-in-progress is an historical novel.

Lethem: I’m writing a book that has scenes that range as far back as the 1930s but centers on the fifties and sixties. It’s taking place mostly before I was alive and certainly before I was really gathering material firsthand. [Laughs.] I’m trying to do a certain amount of that really dull research just to authenticate the use of the material for myself. Even if a lot of the research doesn’t get onto the page (and we probably better both pray that it doesn’t because it’s usually really horrible when that happens). But I just need to be drinking in a lot of information so that I can operate.

Marlow: I do not want to not leave Gun behind just yet because, from that novel, you were courted by the film industry. It was optioned to become a film…

Lethem: This is strangely relevant. That book has had more varied and colorful series of engagements with not-being-made-into-a-film than any of my others, by far. It’s probably about to go into its fourth different stewardship, fourth different development. Let’s call it an ‘area’ rather than a ‘hell.’ I have a stack of screenplays from that one short book. I have enough screenplays in my various storage spaces deriving from that book, several of them completely different. Different writers, different premises, different ways of approaching the material, different drafts. I could probably build myself a pallet on the floor and go to sleep on top of the screenplays of Gun, with Occasional Music.

The other tricky lie about when you’re working in an historical mode is that the most literal version of it is where someone wants to make a movie set in 1957 and so they get an extraordinarily large budget for dressing the set and they buy only clothes, cars, appliances and so forth from 1957. Well, 1957 wasn’t made exclusively of 1957. It was made of the thirties and the forties and the fifties. It was all a jumble of stuff because you don’t throw out your stuff every year. The world doesn’t throw out its thinking or its behavior every year and start fresh. You have to be really careful to notice that 2012 isn’t made up only of 2012.

Marlow: I don’t suspect that you’ll want to do that.

Lethem: No. For one thing, those little brass studs they use to bind them together. Very uncomfortable.

Marlow: For your second novel, Amnesia Moon, it’s a stretch to pull in a film connection, but it does seem to relate to the convention of the ‘road movie’ quite well.

Lethem: Yes. I was thinking about things like [Monte Hellman‘s] Two-Lane Blacktop and Wim Wenders’ Kings of the Road. Those films but also, obviously, the literature that had fed them. In my weird way, that’s as close as I will come to a Beat novel because it just relates to my own yearning towards that material and of reading [Jack] Kerouac when I was a teenager. Eventually, the book proceeds even though it’s not realist or autobiographical in any direct or consistent ways. It also comes really straight out of my own experience crossing the country for the first time, which was enacted when I was 19 years old and done partly by hitchhiking. It was very much the much too late and much too pathetic enactment of a Jack Kerouac quest from the east coast to the Bay Area.

Marlow: That was your own On the Road perhaps? Is that where the Bay Area became a destination? Or did you always…?

Lethem: I think it was mixed up with the different reasons that the Bay Area became a destination, absolutely. I can’t remember if I talked about this at all after the [San Francisco International Film Festival State of Cinema] speech in San Francisco but my arrival in California, I voyaged there through [Raymond] Chandler and Phillip K. Dick and Kerouac. So many different ways, different images resounding for me before I ever arrived there bodily. I was all mixed up about what place I was coming to and what it meant to me. But it meant an awful lot already and it was all a symbolic convergence of my dream of what the American narrative push to the west involved. This utopian possibility. The distance from Europe and the hierarchal northeast. Just all of that stuff and then the collapse of the dream that Chandler had already begun detailing and Phillip K. Dick was describing. So I wasn’t only idealistic about it. I was involved in the romance of the failure of that image.

Marlow: In addition to Chandler, were you reading Dashiell Hammett as well?

Lethem: Sure. Chandler became the one that meant the most to me but I read everything. I was reading a lot of Ross Macdonald [alias Kenneth Millar] who was, on a technical level, extremely helpful. When I say that the hard-boiled novel is a sonnet, it’s Macdonald who purifies it and perfects it that way. He was the one I read to understand how to really make one of my own when I did it.

Marlow: And [Charles] Willeford, to an extent, as well.

Lethem: I love Charles Willeford. I came to him much later. Of course, until those last novels with Hoke Moseley, he doesn’t conform to the detective story. He’s a crime writer in that other vein. The David Goodis or James M. Cain version where the criminal is the protagonist, which is a form that entranced me. I haven’t ever written exactly in that vein. I think I liked that strain of American crime writing even more. It matters even more to me. It relates, in some ways, to literary fiction more directly because it relates to [Fyodor] Dostoyevsky and to Thomas Berger (who has a number of novels that work that way).

Marlow: That is interesting that you say that because I look at Motherless Brooklyn, to a certain extent, as creating a protagonist that is a bit of an antihero in that same vein.

Lethem: I get why you say that but he fancies himself as a hardboiled detective and the book structures according to his fanciful belief. The voice generates out of that fanciful belief.

Marlow: In the mention of books-into-films, I am aware that Motherless Brooklyn was also optioned once upon a time. That still seems like a very difficult novel to make into a film.

Lethem: Some people think easy. Some people think difficult. I’m glad it’s not my job to do it but it’s certainly catnip for filmmakers.

Marlow: It is so well written on the page that it invites itself to be adapted but I don’t know if it could be improved upon. We’ll see, I guess. As for your journey to the west, I can certainly understand the attraction of it. I share it. Did you look at the westerns of John Ford and the notion of the great expanse, the great unknown and those expeditions from east to west? Girl in Landscape shares some of these preoccupations.

Lethem: I came to film in a backward way. Thanks to my parents’ cosmopolitan/bohemian appetites, with the exception of [Alfred] Hitchcock, I watched a lot of European cinema before I watched a lot of classical Hollywood cinema. I really knew [Jean-Luc] Godard and [Francois] Truffaut and [Michelangelo] Antonioni and a bunch of other stuff. Then, of course, I was aware of contemporary English language films that were exciting to my parents and me. Films by [Stanley] Kubrick and [Robert] Altman. I knew all the stuff that you’d see in a New York art house environment as a teenager. Then, in my twenties, I had to go back and figured out how the body of American classical cinema was terrifically important to me. It was really film noir that drew me back. That was when I watched [Howard] Hawks and Ford and [Orson] Welles. The American Fritz Lang films and all these things became really, really powerful and defining for me. I didn’t grow up with them, mostly. Ford was a great discovery of my twenties and I became consumingly interested in him. He’s a counterpoint, in a way, to the narrower stylistic and emotional intensity of film noir or even of someone like Hawks or Welles. He had more of literary amplitude. He’s like a [Charles] Dickens. He puts all of life into the story and he’s not afraid of sentiment in certain ways that the others have to ‘hard boil’ it in order to tolerate it. The Searchers meant a lot to me, in some ways, as an embarrassing but really compelling antidote to the cool of film noir. It probably helped lead me through Girl in Landscape then into the more diverse and sprawling canvas of something like Fortress of Solitude and what I’m working on now. It becomes excruciating hearing myself have to claim the influence, exactly. What mattered was that I loved the movies. I just started to want to devour every Ford film I could see. I probably, to this day, can’t even say why it mattered so much to me then or why they continue to matter to me in retrospect. He just became really moving to me. Someone who I wanted to be around. His voice and his sensibility, even though, obviously, there are great variations. They’re not all as paradoxical. You could study The Searchers forever. You can study The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance forever. Or you can go back to something like Long Voyage Home or Wagon Master and just breathe it in endlessly because it’s so perfect. Then there are a lot of really homely or strange or incomplete pieces like Two Rode Together. This is a movie I wouldn’t recommend to anyone, necessarily. But it all mattered to me at one point.

It’s like bad drugs. It’s like wanting to do a lot of angel dust or something. Film is fucked‑up when it takes a hit of unreliable narration. It mostly can’t recover from that. But I’m fascinated by that impulse. When people have come to me wanting to adapt ‘Fortress of Solitude,’ in a way, I get fascinated and I want to hear what they think they mean. I sometimes even want to try to help them. But I really do think, in some ways, it’s like they’re reaching for the angel dust.

Marlow: It is also interesting that Ford generally was not making films that were contemporaneous with when he was making the film. He was really attracted to working with either the American past or the Irish past.

Lethem: Right. That’s true. He did dodge ever making contemporary material.

Marlow: It happened but it was very infrequent.

Lethem: I never really thought about that exact aspect of his work but it is completely the case. Even when he’s contemporary, he has gone into some slightly exotic milieu, like the Hawaii of Donovan’s Reef or Seven Women or whatever. Some other world where he can impose his poetic vision on society without having to contend with anyone’s notion of what it’s really like now [or then].

Marlow: One attraction of reading Kerouac these days is that you get a portrait of the San Francisco of the 1950s or Phillip K. Dick and a the notion of 1960s Berkeley and Oakland. Much like when you see period films. Much of what you see stays the same. The fashions change but much of the architecture remains.

Lethem: Exactly. Things stay the same. This is one of the things I had to talk about. Everyone saw me with Fortress of Solitude as a great commemorator on a lost Brooklyn. I would literally walk journalists around with me and say, ‘Look. Everything that I wrote about in that book is right here. There’s the crack den. That’s the one I was writing about. It’s there. They had a bust last night.’ But there is this idea that sweeps people up. William Faulkner put it most simply, ‘But the past isn’t gone. It isn’t even the past.’ But the other tricky lie about when you’re working in an historical mode is that the most literal version of it is where someone wants to make a movie set in 1957 and so they get an extraordinarily large budget for dressing the set and they buy only clothes, cars, appliances and so forth from 1957. Well, 1957 wasn’t made exclusively of 1957. It was made of the thirties and the forties and the fifties. It was all a jumble of stuff because you don’t throw out your stuff every year. The world doesn’t throw out its thinking or its behavior every year and start fresh. You have to be really careful to notice that 2012 isn’t made up only of 2012.

Marlow: When someone creates a simulacra of, say, a 1940s movie today, you see these impeccable 1940s cars that they brought onto the set. Look at a picture from the 1940s and that’s not what you’ll see. Not at all. It’s absurd.

Lethem: It’s a constant problem. It’s a fight that you’re probably destined to lose doing the work I’m doing right now. But when I say, ‘It’s best not to let the research get onto the page,’ part of that is that if you read about, whatever, New York in 1961, you’ll imagine that every single person was talking about the breath of fresh air that the Kennedy administration had brought, a sense of reality, because that’s the only way historical writers know to write about things. That this was in the air. But lots of people probably had no idea what was going on or had any interest in it. For them, something entirely different was going on that was just as real or much more real than what you’d find if you researched the time.

Marlow: Yes, exactly. In a completely different direction, you recently wrote book-length analysis of John Carpenter’s They Live. Given your affinity for film, I presume you have been approached to write screenplays? I imagine, at some point, you must have been approached.

Lethem: A little bit. I am always interested enough to have the conversation but I think I screw up the conversation because I don’t really want to get into that behavior. The idea is very interesting to me but the situation is very unexciting. For one thing, I usually have a book that I want to be writing more than anyone can entice me want to write their movie. But also, the first thing that I’m usually asked to do is something that I’ve already done: either to adapt one of my own books or write something like, say, Gun, with Occasional Music. Someone who wants to option me instead of optioning the book and get that thing that they already like. Well, that’s the opposite of why I write. I usually write to move forward and become confused and surprised and fascinated with something that I don’t understand already. I don’t want to reenact some work I’ve already done or some mode I’ve already satisfied myself in. Also, the exact situation that people have in mind when they ask the writer to adapt their own novel is a Chinese finger trap, because everyone, even in asking, is telling themselves, at some conscious or semi‑conscious level, ‘They’ll want to do stuff from the novel that won’t work on film and it’ll be a problem.’ I constantly have to explain to people and it doesn’t work. I can’t explain to them enough that I actually think the best films made from books throw out most of the book and just take some few great set pieces and some essence or some inspiration. My model is Howard Hawks doing To Have and Have Not or Ridley Scott doing Blade Runner where you’re not reverenced towards the source. I think that makes for cinematic, interesting possibilities, whereas I think the Cliffs Notes, obedient scenario, where you end up with Shipping News or something, is just death on wheels. It’s not what I’d ever want to be involved in with my own books or anyone else’s and yet the writer is expected to play that role of the defender of the material. Paradoxically, if I agree to adapt something of my own, anytime I looked at something in the book and I thought, ‘This would work. Let me actually run this scene. This is a set piece. This will play,’ I’ll be feeding the expectation that is was ‘too bad he couldn’t let go of it.’ So it’s a double‑bind. It’s very, very boring, very wearisome. I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to do a thin paraphrase of work I’ve already done. I don’t really want to be hired to think up something incredibly great from whole cloth either because, if I do, I want to write it as a book!

The only thing that I’d probably really be excited to do would be to work with someone who I thought was a terrific director—since I suspect that’s where the action really is, not in the screenplay—and collaborate on an idea they had. That way, I wouldn’t get greedy and want it to be my novel instead or fuck up somebody else’s book. In that exact scenario, the number of directors I’d be thinking of is fairly small. Many of those same people are good writers and write their own screenplays or do it with some old friend of theirs. That’s very understandable. It’s what I would do. So I just haven’t been asked in the circumstance that would actually tempt me to get involved in that extremely humbling, compromising, strange environment that is Hollywood. In many ways, also, I like staying a fan. Like I said, I don’t want to necessarily professionalize my movie love to that extent. I’m not naïve. I know a lot of filmmakers. It interests me to talk about film. I like that the books are optioned because it gives me a proxy involvement. I feel like a tiny little bit of my writing life is in there, in the mix, trying to become a film. But I don’t want to have to do it myself.

Filmmakers go to books looking for a feeling that they have begun somewhere instead of nowhere. I think it’s terrifying to try to make a film. The number of collaborators and resources and the things you have to believe are all going to come in support of your attempt. It’s so daunting. It’s so terrifying. A book is like a prop. It wants something already there, that’s already good, that you can already like and you can point to. Instead of pointing at a giant vacuum, you can point at this book and say, ‘We want to do something like this.’ Well, thank God. I’ve been able to write for years on the options on unmade films!

Marlow: I don’t blame you. You mentioned J.G. Ballard earlier. When I spoke with him shortly after Empire of the Sun was released, I mentioned how surprised I was that, of all of his works, Empire was the first to make it to the screen. He agreed. Years later, obviously, [David] Cronenberg made Crash and a few of his other books have also been adapted. How do you feel about the assorted adaptations of the books that you have adored in your life, whether it be the works of Philip K. Dick or….

Lethem: An adaptation of something that you care immensely about is always really estranging and interesting. It creates a static. Actually, the first time I saw Blade Runner, I was kept from seeing what a terrific film it was because I was entrenching in a very simpleminded way behind the idea that Dick’s work hadn’t been adequately represented by it. Well, who cares? As I said, I quickly came around to seeing that as very much a best‑case scenario to have happen to anyone’s book. It just can’t be made on occasion like that. I think a lot of people are quite mixed up and I don’t see it as my job to try to straighten them out in any way. I might be wrong. I feel that many people are deeply confused about what it is in books that have made them excited enough to think they want to option the book. Just as you said, the action in ‘Motherless Brooklyn’ is really in the language. I agree with you. I think one of the weird things is it’s almost like a death impulse, collectively, on the part of film culture, that it wants to adapt the thing that is least adaptable. It wants to adapt viewpoint or language or unreliable narration, when it’s got so many gifts and, in many ways, so many advantages over narrative writing that it ought to be exploiting those instead of pursuing these… It’s like bad drugs. It’s like wanting to do a lot of angel dust or something. Film is fucked‑up when it takes a hit of unreliable narration. It mostly can’t recover from that. But I’m fascinated by that impulse. When people have come to me wanting to adapt Fortress of Solitude, in a way, I get fascinated and I want to hear what they think they mean. I sometimes even want to try to help them. But I really do think, in some ways, it’s like they’re reaching for the angel dust, which is not how I feel when someone might reach for Gun, with Occasional Music. The ultimate example of this is that of my own books, the one that has solicited the fewest inquiries from filmmakers is the one that is completely filmic: Girl in Landscape. Obviously, you have to make some decisions about how you’re going to render the unreal world. But in terms of the scale of the story, the unfolding, the number of characters, it basically is a film, and I know that because it’s basically The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. In terms of its scale and its plot dynamics, it’s that much more than The Searchers. Spiritually, it’s related to The Searchers. Filmmakers go to books looking for a feeling that they have begun somewhere instead of nowhere. I think it’s terrifying to try to make a film. The number of collaborators and resources and the things you have to believe are all going to come in support of your attempt. It’s so daunting. It’s so terrifying. A book is like a prop. It wants something already there, that’s already good, that you can already like and you can point to. Instead of pointing at a giant vacuum, you can point at this book and say, ‘We want to do something like this.’ Well, thank God. I’ve been able to write for years on the options on unmade films!

Marlow: That’s a plus, definitely. As someone who revisited Omega the Unknown, what do you think of this strange attraction in Hollywood to superhero films? The thing that I’ve always found discouraging about these movies—one of many—is the attraction or the adherence to the origin story. I just don’t understand what the point of it is anymore.

Lethem: This frustration with the origin story is something that I actually relate to a widespread and elusive but thoroughgoing defect in our culture in terms of narrative. It is a form of backstory obsession that infects film but also creates an endless appetite for memoir. You always want to know where everything came from. They made Dr. Seuss’s ‘How the Grinch Stole Christmas’ and they gave the Grinch a backstory! He was traumatized. This is most innervating and, again, it’s so antithetical to what film does well. When I watch a great film, almost invariably the director knows that you put characters in a situation and you start a story and you don’t bother to glance backward once, because if the actors are compelling and the story is compelling, you are enmeshed.

Marlow: Correct.

Lethem: You don’t need the reassurance that they were nice to children and animals nor do you need to know where their pain came from or anything that happened before the story. Novels can dabble in flashbacks and backstory, although even that gets very, very labored and it’s overvalued. But films shouldn’t ever touch it. And yet, you’re right. The whole superhero fixation seems to be on how we got there. Forget it. It’s really, really dull! It makes every story into the same story. It makes every story into a biopic, which is the worst genre film Hollywood ever generated, until the superhero film.