Editor’s note: This article highlights films from the Criterion Collection via Hulu themed “That Old-Time Religion.”

It would be unfair and inaccurate to say that film art doesn’t address religious or spiritual questions today. But I do think it is fair to make a few general diagnoses about how spiritual cinema has evolved —perhaps not for the better—since the grand moment of international art cinema of the 1950s and ’60s. For one thing, the educated, self-selected audiences for world cinema have possibly inherited a greater, postmodern skepticism toward religion, which has resulted in a shift in tastes and canons for the 21st century. For that matter, the larger part of the international filmmaking class—those directors who tend to fill out festival line-ups and distributor slates—is comprised of relative agnostics. This is not a criticism, but it does mark a difference from the era of Bergman, Dreyer, and Pasolini.

But then, there is a much larger problem, which has to do with representational orthodoxy. Pasolini, we must recall, was not only a Christian but also a Marxist, which led him to make a very materialist (yet Vatican-approved!) version of The Gospel According to Saint Matthew. But when Martin Scorsese took on The Last Temptation of Christ, many Christians worldwide protested the film’s depiction of Jesus as a flesh-and-blood man of desires. In more recent films, from Noah to Exodus to a whole bevy of Abel Ferrara productions, religious themes have been broached to the consternation of many. We live in ultra-literal times, it seems. Religion, one of the deepest motivating experiences in a believer’s life, must not be explored by artists with any degree of interpretative license, lest their spiritual vision offend someone. Better to limit “religious cinema” to church-sanctioned, moralist fodder like God’s Not Dead or Persecuted.

There is still great cinema being made that draws inspiration from spiritual inquiry. One need only consult the films of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne (again, Marxists!) to see this. But for the most part we must return to the Masters for examples of serious-minded films willing to engage with the God question. No filmmaker in the Western tradition has plunged deeper into the paradox of faith and doubt than Ingmar Bergman. For his trouble he became, for a time, a code word for a form of art film seriousness bordering on self-parody. The great opening scene in The Seventh Seal, in which the weary Antonius (Max Von Sydow) challenges Death to a chess match on a deserted beach, has been clowned upon by everyone from Carol Burnett to “Bill and Ted.” However, time has come around and returned the titanic grandeur to Seventh Seal. Set at the collision point of the Crusades and the Black Plague, the film is about the existential tug at the heart of faith. Belief is an action, one that we perpetuate, or not, in the face of insurmountable worldly evidence.

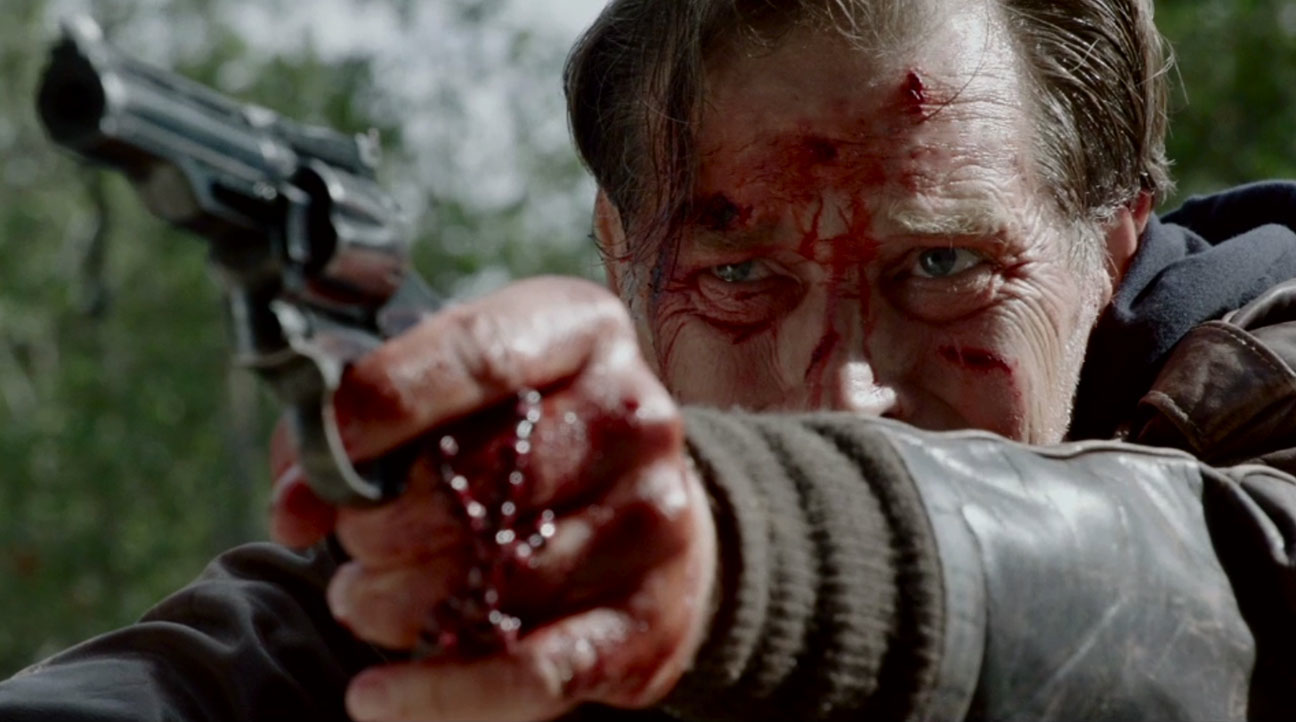

Likewise, Bergman explores the conflict between charity and barbarism in The Virgin Spring, situating the crisis at the crossroads between paganism and Christianity. Karin , a young virgin, is raped and murdered in the woods while on an errand with her half-sister Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom). Did Ingeri bring this tragedy about because she prays to Odin every day to curse her sibling? And when the perpetrators of the unspeakable crime unwittingly seek food and drink at the home of Karin’s parents, will the dead girl’s father (Von Sydow) rise above his animal instincts or exact bloody revenge? Given that Bergman ends the film with a miracle (in keeping with the Swedish ballad on which Virgin is based), he seems to possibly implicitly validate the father’s decision. But what is clear is that Karin was indeed too good for this world, and now, having been returned to the earth, infuses it with new life.

Bergman’s disquisitions on God were a bit too talky for some (in keeping with the age of existentialism); other filmmakers of the era were lionized for the sheer physical force of their filmmaking, the presumption that in laconic devotion to the material before them—the image itself—a spiritual meaning would emanate and touch the sensitive viewer. Robert Bresson’s films were not always religious in theme, but his fixations on grace, sin and redemption (key tenets of his Jansenist theology) permeated his oeuvre, lending even his most “profane” works a spiritual ambiance.

Bresson’s The Trial of Joan of Arc runs a lean sixty-five minutes and its overall parsimony makes Dreyer’s own Jeanne d’Arc look extravagant by comparison. Although Bresson uses the actual transcripts of the Joan of Arc trial (resulting in some rather verbose passages), large portions of the film withhold her face, or show only her hands or feet. Using close-ups and fragments, Bresson accomplishes some unusual effects. Not only is he restricting himself to a kind of zero-degree of filmic communication, analogous to a monk’s vow of poverty. But in displaying Joan as a series of parts—making her a human synecdoche—Bresson ironically makes it easier for us to identify with her, not in a psychological way but as a representative of humanity. This is spiritual cinema: to take on the suffering of another as our own, and to be lifted up by that imitation.