[Editor’s note: This week’s selection of Criterion-via-Hulu films centers on the theme of “Special Effects.”]

Two formidable debuts are represented in two films that share little else besides their horror-genre classifications: 1958’s The Blob, which boasts Steve McQueen in his first leading role; and 1993’s Cronos, the first feature by Guillermo del Toro.

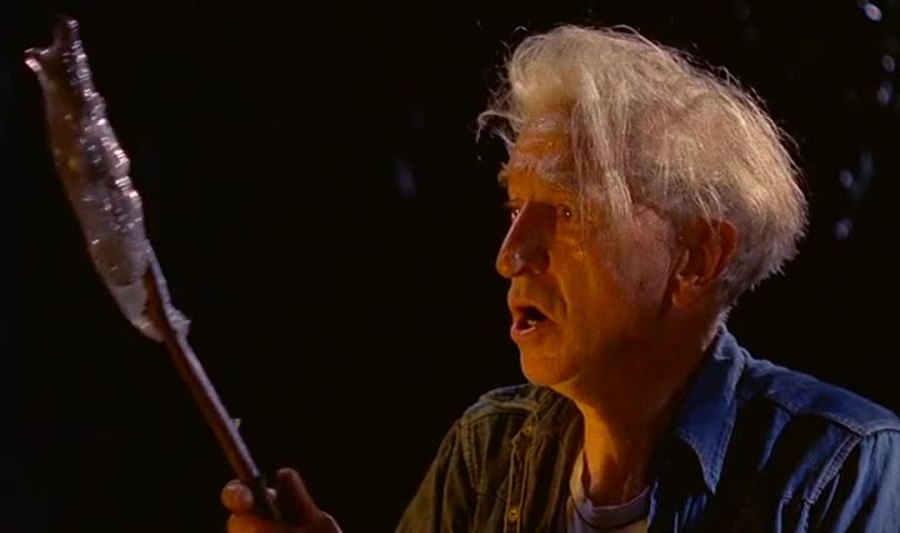

Low-budget chiller classic The Blob announces itself as not to be taken entirely seriously with its tongue-in-cheek opening credits song, a novelty jam co-written by Burt Bacharach that suggests “beach party” more than “monsters a-comin’!” We meet Steve (McQueen, billed as “Steven”) and girlfriend Jane (Aneta Corsaut, who’d later find fame as Andy’s girlfriend Helen on The Andy Griffith Show), who are arguing on lover’s lane —the young lady’d prefer not to be called “Janie Girl,” thanks very much—when… something… blazes down from the sky and into the nearby woods. Beating the eager teens (while dashingly charismatic, McQueen was actually pushing 30, and looks it) to the crash site is a hermit type (veteran character actor Olin Howland in his final role), who learns the hard way not to poke a stick into something weird and hostile that comes from outer space.

It doesn’t take long for the titular beast, which resembles a sticky pile of melted-down gummy bears, to make its intentions clear; before long, it’s consumed the old man, the town doctor, the doctor’s nurse and a pair of hapless mechanics, one of whom leaves this mortal coil excitedly planning to get “roarin’, stinkin’ drunk” on an upcoming night away from his wife. Meanwhile, Steve and his car-racing buddies have a run-in with the fuzz (“What am I gonna do with you kids?” the cop wonders, probably not for the first time)—whose disregard for the town’s teenage population means they ain’t having it when Steve tries to warn them about the a giant, flesh-gobbling heap of red gelatin slowly lurching its way down main street.

Steve soul-searches (“How do you get people to protect themselves against something they don’t believe in?”), and The Blob morphs into a film that’s less about space invaders and more about the dangers of not trusting someone who is genuinely asking for help. That said, it does contain a scene in which the Blob consumes an entire greasy spoon diner, and an early example of horror’s love for self-referential humor when the creature oozes into a theater of screaming kids taking in the late-night “spooky show.”

Far more mournful (and, it goes without saying, way more exacting in the mise-en-scene department) is Cronos. It begins with a narrated backstory about a 16th-century watchmaker-turned-alchemist who created “the cronos device,” a palm-sized, steampunky contraption that contains the secret of eternal life.

Wherever there is immortality, there’s someone who’s willing to do anything to get it, but the device—missing since its inventor’s eventual death in the 1930s—has eluded the grasp of rich, dying Dieter de la Guarda (prolific Mexican actor Claudio Brook), despite the best efforts of his blowhard nephew (subsequent del Toro regular Ron Perlman, who turns in a wonderfully out-there, obscenity-laden, nose-job-obsessed performance).

The man who does have it doesn’t understand what it is until it’s too late: elderly antiques dealer Jesus Gris (Argentine actor Federico Luppi, another del Toro regular), who finds the strange object tucked into the base of a crumbling statue. When he curiously manipulates it, it whirrs, clinks, and latches on, and Jesus’ unfortunate transformation begins.

What unfolds (gory body horror, a young child wiser than her years, supernatural elements that are as alluring as they are nightmarish) hints at what was to come for del Toro, who’s since become one of the most unique stylists in the horror genre. But even taken on its own terms, Cronos is a haunting film, elevated by a tone that’s elastic enough to incorporate both deep sorrow and daffy humor.