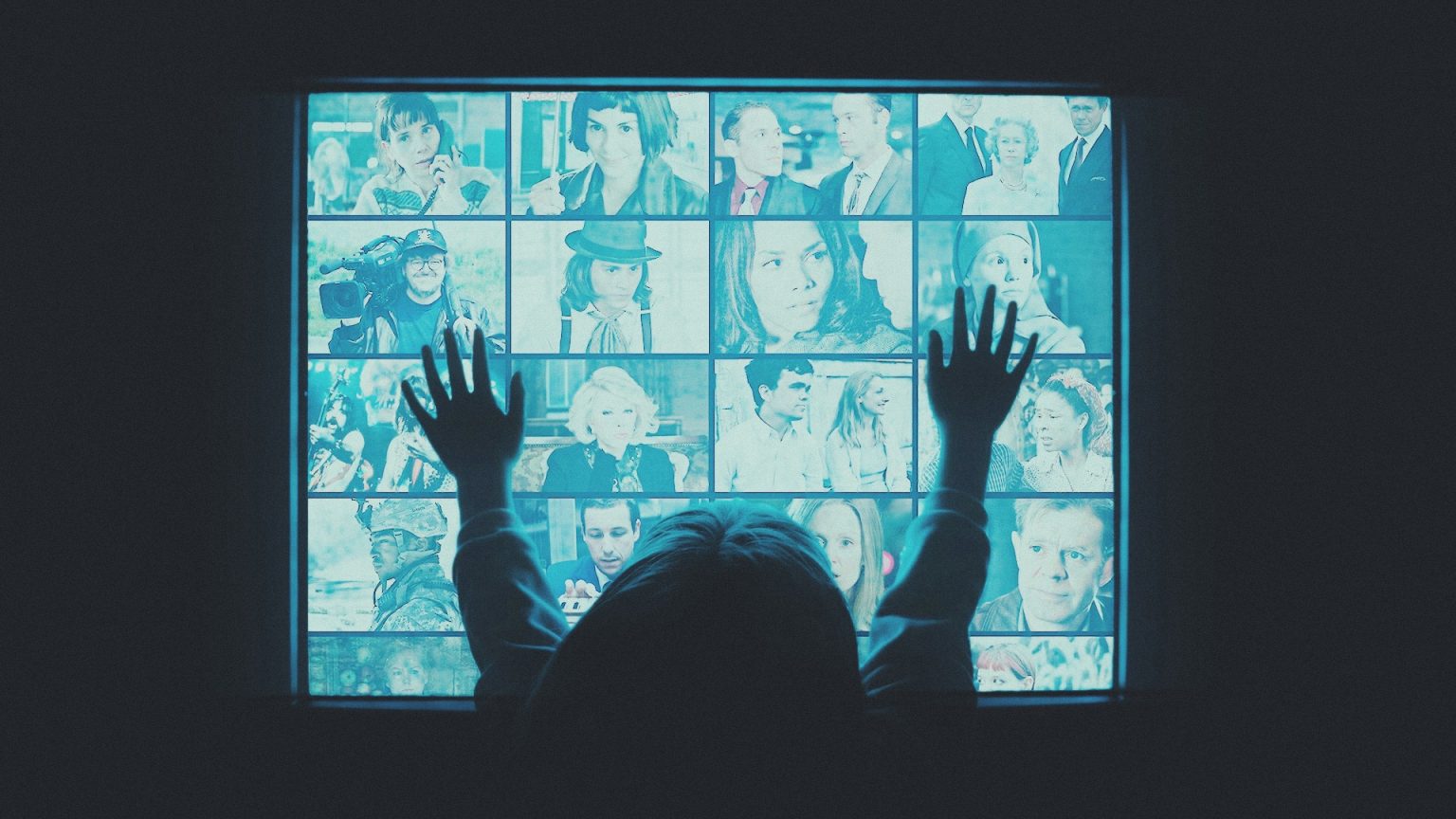

As the world becomes more and more visual—whether it’s the stories we watch, the advertisements we are shown, the news we are told, or the media we create—the power of film has become increasingly more prominent in our everyday lives.

Yes, our visual literacy has greatly increased since the rise of social media, the twenty-four-hour news cycle, and reality T.V.—even videogames are becoming increasingly cinematic, with the most recent God of War imitating a single long-take for the entirety of its gameplay. But through all of this, there are debates over whether this visual literacy is being used as a tool to help us interpret not only film, but the world around us, or whether the film and editing techniques pioneered by cinema are now being used as tools of manipulation. Just how aware are we when a news broadcast, meant to transmit objective information, uses an editing technique to subtly communicate the desired emotion? This is why cinema, its history, theory, and production should be required learning in educational systems throughout the United States.

In terms of the media we consume, while we may recognize when an edit occurs, how often do we actually think about how this subverts the message and narrative of what we are watching? And beyond that, and perhaps most importantly, does this subvert what we think of as “art?” Does art still have a place within commercially-driven industries, like Hollywood? In other words, because these film techniques have become so ubiquitous in our society can we now not help but take the film as an art form for granted?

It’s alarming that so much of today’s media is taken for granted and rarely, if ever, analyzed outside of strictly narrative confines. The idea of “What will Kylo Ren do next?” is more important than the fact that The Last Jedi was a comment about how everyday people, as opposed to a chosen few, have the ability to affect the lives of many in a positive way. And both of these things pale to the seeming importance of harassing one of The Last Jedi’s brightest sparks, in actor Kelly Marie Tran, to the point that she felt like she had to disappear from the Internet. Because of this misunderstanding, or lack of awareness, of the actual power of the medium, even the most tech and image savvy amongst us are almost naive when it comes to considering how, why, and what movies are truly conveying beyond the surface level.

English, drama, theatre, and other art forms have long been studied, discussed, and appreciated for their ramifications on society (even if in our current society these subjects, too, are neglected). We read George Orwell’s 1984 and ponder if society continues to inch closer to dystopia, but hardly ever will we watch a movie like Children of Men and wonder the same—at least not in school.

The film has influenced and inspired nearly every other type of visual media. News broadcasts borrow basic principles of cross-cutting to expand their coverage and illicit drama. Video games rely on cinematic techniques to tell their stories. Yet the film is arguably the most neglected art form when it comes to serious scholarly consideration, prior to what a student may encounter in college. Studying film could lay the groundwork for us to better understand the “tricks” filmmakers, marketers, advertisers, vloggers, and news producers use to relay information about the world around us; it could be the foundation for students to better understand why each form of media we consume, down to a simple text message, is meant to be parsed; it might just be what our culture needs in a time rampant with fake news…not to mention simplified Hollywood schlock and unnecessary sequels.

And beyond how serious study of the film could impact our day-to-day lives, it could also lead to a real possibility that more people might put aside Batman, Ironman, Titanic, Avatar, and Transformers, and instead check out the work of Bergman, Truffaut, Kubrick, Hitchcock, Dreyer and many others. It’s not that we can’t enjoy popular entertainment, it’s that we shouldn’t be afraid of exploring art.

By expanding the breadth of how we think about film and, in general, all visual mediums we might become more receptive and critical of how films might broaden our cultural understanding. Imagine if instead of only a few million people seeing Barry Jenkins’ masterful Moonlight that it was as popular as Infinity War. Imagine then, a high school class talking about the essays of James Baldwin and applying those ideas about race and otherness to a film like Moonlight. How might that affect society?

Films can also be used to teach about politics, war, propaganda, or they can even be used as a way to empathize with the people we otherwise might never know or understand—I mean, how is Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, not required viewing? This isn’t to say everyone needs to jump aboard the Frankfurt School Theory and assume mass cinema and visual media are capitalist forces distracting us from the harsh realities of the world. But this also isn’t to say that we should shrug off the power of film as simple entertainment.

As with any scholarly subject, the passion and a desire to learn are required for the information to take hold and feel relevant, but the world already seems receptive to the reality that images are a large part of what “makes” our culture. The next step is teaching and communicating to people how to contemplate those images. It’s then that we might live in a better, more thoughtful world.