David Thomson has always had a singular view of Hollywood. A child of World War II (he was born in England but a resident of the U.S. for some four decades), he was touched to the core by images, dreams and illusions beautifully crafted thousands of miles away in sunny, spoiled Southern California. Thomson is the quintessential outsider, even if he eventually gained access to insiders, and he has long coupled his love and admiration for movies with a concern for the ways in which they sedate, seduce, betray and distract us. He’s taken various droll yet laser-sharp approaches to examining the insinuating effects of the 20th century’s most popular medium, from iconoclastic biographies (Warren Beatty and Desert Eyes, Showman: The Life of David O. Selznick, Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles, Nicole Kidman) to collections of musing essays (Beneath Mulholland: Thoughts on Hollywood and Its Ghosts, The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood) to indispensable thumbnail analyses (The New Biographical Dictionary of Film) to excavations of favorite films (The Moment of Psycho, Have You Seen…?) His new tome, The Big Screen: The Story of the Movies, sprang from his publisher’s request for a one-volume history of the movies. Thomson provides that, with his customary wit and gift for the telling detail, accompanied by a rueful acknowledgement that the screen has come to supersede the image over the course of a century. The movies have altered our relationship to life and the world, and not for the better. I interviewed Thomson in mid-September at his home in San Francisco, not the first time we’ve had a conversation in his living room with a tape recorder on.

Keyframe: One of your subthemes is the transition from the theater screen to smaller screens, and the way people watch movies now. But is this not a conversation that began with ‘The Late Show,’ when movies were first broadcast on television, long before VHS (let alone DVD)?

David Thomson: It goes back even further in that what Edison first envisaged is one person, one viewing machine. A situation much more like television: a fairly small screen. And if he had had his way we might never have gone to projected films. We did. But the thing you’re talking about—this is a big simplification—whereas for a long time human beings and film critics and filmmakers thought they were watching films or stories, moving imagery, which obviously they were, they didn’t realize until let’s say the last 15 years that what we were really looking at were screens. And as screens have multiplied and taken such strange, seemingly impossible and unwatchable forms, shapes and sizes, it suddenly becomes clearer that we spend an inordinate amount of time watching screens.

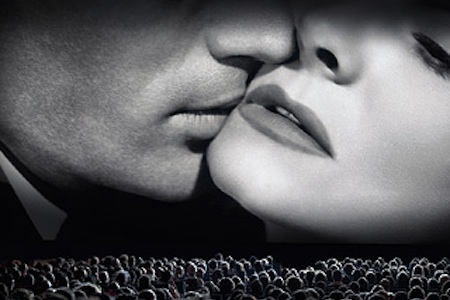

Now it’s certainly true that that phenomenon began with television, although it was relatively unnoticed at the time. So that someone who had been a really regular moviegoer might have watched, let’s say, six hours of screen time in a week at the movies, three films, would now be doing six [hours] and more a night or a day. We sort of said, ‘Well, is this a good thing? Is this good for children? Or for adults?’ But it’s only, I think, as the screens have invaded our life in so many ways that it’s become clearer. But what I try to do with this [book] is to say that from the very beginning the screen was not just a means of carrying the message. It was a new kind of way of handling reality, which was to put it at a distance and say, ‘What are of the most extraordinary things in reality you’d like to see?’ And you say, ‘Well, I’d like to see the pyramids in Egypt.’ OK, pyramids in Egypt. ‘I’d like to see lions on the veldt.’ OK, you got it. ‘I’d like to see people killing other people.’ OK. ‘I’d like to see people having sexual intercourse.’ OK. We can do it. And more or less the film industry has been based upon the principle of ‘Show them something they’ve never seen before. ’ And it still works to a degree.

But what I think was not recognized very much early on was that the setup—us in the dark, screen bright—was a model for a kind of helpless distancing from reality, a separation from reality which I think has led—I don’t say it’s the only thing that has led to it—to a condition where we think we are helpless with the world. So, for instance, if you look at the present situation, we know intellectually that we are about to go through what could be the most important election of our time, and yet nobody in the election has mentioned the cliff that’s coming. Nobody has really mentioned global warming. The things that could almost literally mean the end of the world are ignored, and tiny, gossipy little squabbles become what politics is about. And I think the model for this is, ‘Oh, you want to see someone being killed? Of course you can see someone being killed, but of course, you can’t save them.’ In real life if you see someone being killed, you feel—you may not have the courage, but you feel you should intervene. You should participate in life. I think it is the model for a way of thinking that says, ‘We don’t need to participate in life in the same way.’ So I think it’s amazing that in our present state, and I mean our present state all over the world but particularly in America and Europe with the sort of prolonged unemployment and austerity and poverty and so on, there’s not been disturbance, there’s not been rioting, there’s not been unrest, there’s not been an uprising in the way that there was in the sixties. I think it’s a measure of how far we have become neutralized and nullified.

So that’s what the book is about. Now, it’s a history from Muybridge to Facebook of the whole process. And it celebrates a whole lot of films and filmmakers but it’s working towards that conclusion, which is unquestionably a pessimistic conclusion for someone who’s spent a life loving film. I don’t think I’m alone in that. I think an awful lot of people who’ve been devoted to film and given their life to it in one way or another are in a state of great doubt at the moment. They don’t know where it’s going, what it’s doing. We have this feeling that technologically the change has only just begun, that there’s a whole avalanche of things to come. And you know, whether in 10 years’ time there will be theaters, whether there’ll be things we call movies even, I mean there’s so many things now on YouTube and equivalents to YouTube that are two or three minutes long, and kids spend a lot of time watching them and making them. There are amazing two- or three-minute videos about cats. Which, of course, any kid can make with equipment that is so easy. And where that’s going, I don’t know. The energy, the ideas, the passion for old-fashioned narrative films is not looking good. And it wouldn’t take much for it to become simply a thing of the past. For a time, people thought the long novel was a thing of the past. It has come back, but there was a period when people thought that.

Keyframe: What are the implications for film as an art form?

Thomson: I have always been skeptical of the notion that film is an art. I’ve always thought that it’s a technology, a business, an entertainment and an art, but they’re all mixed up together and they all compromise each other. And I think the auteur theory was immensely valuable for a time in film studies but it was based upon fallacies, which was that one person made the film. What made the film was a group of people, it was the studio system, and it was the culture of the times, it was what people believed in. And it flourished and flowered for a while but it’s clearly gone dead now, although it has, I would say, passed over to cable television. I think it’s easier for kids to express themselves in moving imagery now. When I was just coming out of film school, it was so difficult to get hold of equipment and to make a film. In budgetary terms it was just beyond you. And film seemed a very, very elite practice. That’s changed completely, and some kids make two or three films a week. I’m not saying they’re good, but they express the kids. And, you know, maybe they’ll lead to something better. I don’t think we are going to reclaim, let’s say, the era of Bresson, Buñuel, Bergman, just to keep it in the Bs. That was a period, that was a time. If you remember it, only a few years ago, Antonioni and Bergman died on the same day. It was a very symbolic event. It was like saying, ‘OK, guys, that kind of cinema is over. Now it may come back in some form, but it’s over.’ That’s sad, because those are still some of the great films, but it’s so much more possible for women to make films. And you remember a time when women were only the subject of films. It’s so much more possible for kids to do little things, some of them amazing. Some kid—I saw this on YouTube—some kid did a version of De Palma’s Scarface. Have you seen this? It lasts, like, a minute and 20 seconds. And it is only every use of the word ‘fuck’ in the film. Well, it so encapsulates De Palma that you can never watch the whole film again. (Laughter.) It’s stunning! It’s such a simple but signal moving on to a different culture and it’s very entertaining. And I think afterwards if you were to sit down and watch the whole Scarface—which is not a bad film—it would kind of seem irrelevant, if you know what I mean.

What I try to do with this [book] is to say that from the very beginning the screen was not just a means of carrying the message. It was a new kind of way of handling reality, which was to put it at a distance and say, ‘What are of the most extraordinary things in reality you’d like to see?’ And you say, ‘Well, I’d like to see the pyramids in Egypt.’ OK, pyramids in Egypt. ‘I’d like to see lions on the veldt.’ OK, you got it. ‘I’d like to see people killing other people.’ OK. ‘I’d like to see people having sexual intercourse.’ OK. We can do it. And more or less the film industry has been based upon the principle of ‘Show them something they’ve never seen before. ’ And it still works to a degree.

Keyframe: Likewise it’s hard to watch Downfall after the millions of parodies of Hitler.

Thomson: Exactly! That whole run of parodies of Downfall. Did you also see The Trip? The English film with Steve Coogan? Well, there’s this passage in The Trip (which was TV first, in Britain) where the two guys, Coogan and [Rob] Brydon, they do competing Michael Caine impressions and they’re superb. And I have noticed that I can’t watch Michael Caine again since then. (Laughter.) They wrapped him up and put him on the shelf. Which is not to say that Michael Caine was not a very pleasing, charming, entertaining actor. In parody, which is what they’ve done, you can transcend the original form. It’s never going to be the same again, you know. And I think a lot of interesting things are happening like that.

Keyframe: Let’s look at appropriation from another angle. Blow-Up may not have been the first but it’s a good example of a movie where it calls our attention to the fact that we’re watching images.

Thomson: Absolutely.

Keyframe: And of course Peeping Tom.

Thomson. Yeah. Sure.

Keyframe: We see it a lot now with documentaries that remind you that what you’re watching is someone manipulating images.

Thomson: Like the Sarah Polley film [Stories We Tell]. That’s really what that’s about, too. I’m not saying there’s nothing interesting out there. I’m just saying you’ve got to be ready to look for the interest in different forms. And there’s no point in going to see, I don’t know, whatever the big Hollywood film of the Christmas season is. I’ll speak in advance: I can’t believe that Lincoln, all the technological advantages [Steven Spielberg’s] going to have, and for all the brilliance that Daniel Day-Lewis will bring to it, I can’t believe it isn’t going to feel like a film that could have been made in 1865. And for Spielberg that would be praise for the film. I think that what Spielberg has missed now is that there is a young audience that just isn’t going to sit there for a film about Lincoln. It seems like a ridiculous prospect. So I don’t look forward to that kind of film anymore.

Sometimes you’re surprised. I thought Inception was a pretty marvelous film. There are a few things like that. Certainly in the independent field, overseas, there are some wonderful things coming along, but I’m still not sure that the most interesting things, in the way that Godard was so interesting in the sixties, the most interesting things, the most innovative, aren’t these very short, explosive little jokes or whatever that you can see on places like YouTube or they could be very, very long films. For instance, I never want to see Psycho again simply because I’ve seen it so many times that the quality of suspense, that for Hitchcock was obviously vital, I’ve just worn it away. It’s like an inscription you can’t read any more. But 24 Hour Psycho—have you seen that?—24 Hour Psycho (1993) is a sort of art installation made by a man named Douglas Gordon in which, I forget how many frames a second he’s got it now, but he’s reduced the film, expanded the film into something that plays 24 hours.

Keyframe: He slows it down.

Thomson: Immensely. And I’ve only seen parts of it, I have not seen the whole 24 hours.

Keyframe: It’s a deconstruction, in a way.

Thomson: It is. It’s an interference, and I don’t know whether it’s legal or that kind of thing, but it brings the film back to life. You start to watch and you say, ‘Oh my God, it’s so beautiful!’ And of course, at that speed, it’s not about suspense, it’s about composition and it’s about tiny flickers of a face that you hardly see when you’re looking at it in real time. So it is a different form.

Keyframe: It’s not about the story, either.

Thomson: No, it’s not about the plot. It’s much more about shapes and time. But I found it enormously exciting. I would happily see another couple of hours of that tonight, whereas, to watch Psycho would be a chore. Not that I don’t admire Psycho, you understand.

Keyframe: Some might presume that The Big Screen is, in part, a lament that movies no longer hold the same place in our culture and in us. But your view is more along the lines of, ‘This is the way of the world, and there’s not much point in railing about it.’

Thomson: Exactly. I make a big point in the book how the golden age of movies wasn’t just a time when movies were made in a certain way but it was a time of depression and warfare where the fact of audience was vital. The audience huddled together for comfort, for shelter, for association, feeling of kinship, and believed in the films as part of the effort to overcome depression and war. It’s very old-fashioned now. If you see a film like Mrs. Miniver, which won Best Picture in its day, it’s laughable. It’s terrible. But you have to imagine and remember that when people saw Mrs. Miniver, they were deeply moved. That’s how it got Best Picture. Now, that culture exploded. It started to explode with television. There’s no question. There’s a lot in this book about the impact of television. And television was in such quantity that it destroyed story, because it told so many stories that every time you watched something you said, ‘Haven’t I seen this story before?’ We’ve got a limited number of stories, and so it just became redundant.

Actually, I think that the screen in the form of the computer, the iPhone, the iPad, has been a very exciting move. And there’s a great deal going on there and there’s a great deal more to come, so I think in that sense it’s optimistic. For the people born and raised to the big Bs, the people we talked about earlier, that can seem sad. It will be sad if the general run of movie theaters closed. And it will be sad if it becomes nearly impossible to watch some of the great films on film on a big screen. Now, I think those things are going to happen. They’re happening already. You know that by the end of next year, almost all projection in America will be digital. It will not be film. Film is just fading away. And those are losses but as you say, there’s nothing you can do. I mean, you can say it’s a great pity that man split the atom, but you can’t put it back in the bottle, and we have to live with those things, and actually far, far more pressing a problem than film is what are we going to do with the hydrocarbons. How are we going to solve that?

Keyframe: I’m old enough to remember when TV stars couldn’t make the transition to the big screen. Once audiences didn’t have to pay to see someone, they weren’t going to buy a movie ticket for the privilege. Nowadays people watch movies on computers and tablets, and don’t seem to differentiate between big and small screens.

Thomson: You think of a city like San Francisco which, as you know, is much more movie-friendly than most cities in America. How many really big screens do we have? We have the Castro. We have the Paramount over in Oakland. But one of the places we go to [has] screens that are much smaller than we would have accepted in our childhood. They’ve all got smaller already, and that’s going to increase.

Some kid—I saw this on YouTube—some kid did a version of De Palma’s ‘Scarface.’ Have you seen this? It lasts, like, a minute and 20 seconds. And it is only every use of the word ‘fuck’ in the film. Well, it so encapsulates De Palma that you can never watch the whole film again. (Laughter.) It’s stunning!

Keyframe: Let’s talk about the relationship between real life and movies, or real life and stories. In the 1920s, say, it was easier to separate the two. You lived your life, and you went to the movies and said, ‘Look, this movie was shot in my neighborhood.’ Now, you watch a sunset and say, ‘It looks like a movie.’ We’ve seen reality presented so many times that we experience it not as if we’re in the moment but through some previous association.

Thomson: There’s a scene in Don DeLillo’s White Noise, which I refer to in the book, where people are taking photographs of an old New England barn. It’s a tourist attraction and a character says, ‘They’re not taking photographs of the barn any longer. They’re taking photographs of photographs.’ And that has happened. Blow-Up is a film that was on to that in a very, very witty way. It’s a thriller but it’s a very comic film, a very interesting film. And the idea of whether he has seen a murder or not, that whole thing, is very intriguing, and very, very special. Of course, in 1966 when that was made, the power to manipulate the image was so much less than now. We know more or less what film can do now, so you ought to begin to wonder how much of that has been done on television newscasts, things like that. We know enough not to trust quite what we’re seeing. Whereas when movies began, people trusted.

Keyframe: What are the implications for nonfiction? Not from the standpoint of manipulation but from the standpoint of detachment and distance. We react to an image of a starving child in Ethiopia, not a starving child in Ethiopia.

Thomson: I think nonfiction has become a genre. It’s become a genre of fiction. It’s a style. It’s like the musical. It’s one of the genres we’ve invented as we have killed some of the others. I think it’s impossible to make a documentary that doesn’t look like a fictional film, a made-up film. And one of the very interesting things about documentaries is if you examine the credo behind documentary film it’s that documentary film can change the world. Well, name me a documentary film that’s come anywhere near changing anything in the world. I’m sure there are some.

Keyframe: The Thin Blue Line might have gotten someone off Death Row.

Thomson: Very few. You know, basically, it’s another way of making films.

Keyframe: So where do we go from here? Not to give away the ending of the book, but what’s next?

Thomson: I don’t know beyond saying, ‘Look what’s here now.’ I think more and more of the moving imagery we watch is going to be shorter or longer. I think we can explode the idea of a certain length, and we’re going to watch it partially. One of the things the DVD has done is to say to us, ‘You don’t have to watch the whole film.’ We all of us know certain scenes in certain films we love, and sometimes at home in the evening we’ll put the disc on and we’ll go to the chapter that we really love. People do that more and more. I think all of those things are going to increase. And I think that what’s left of the mainstream, like Hollywood, like network television, they’re sort of half-abandoned houses. I wrote an essay a year and a half ago where I said the time has come to tear the Hollywood sign down because it’s so inaccurate, it is so artificial, and so demented. Now you can see how ugly it has always been! (Laughs.) So tear it down because Hollywood doesn’t really exist anymore, and let Los Angeles develop and become Los Angeles. It’s a joke, but I’m serious about it. It’s like Commedia dell’arte, that doesn’t exist anymore. That doesn’t mean its influence doesn’t work in some places—certain clowns, certain operas, that kind of thing. But it’s silly to regard it as a current thing. And Hollywood is no longer current. The Oscars, in my opinion, should be abandoned. They’re derelict. The massive awards shows we have now, and the business of Top 10s at the end of the year, it’s just nonsense. It should all be thrown out.

And I think that what’s left of the mainstream, like Hollywood, like network television, they’re sort of half-abandoned houses.

Keyframe: Why?

Thomson: Because some years there aren’t 10 films worth putting in the Top 10! (Laughs.) And some years there literally isn’t a Best Film, because there’s not really been a good film. It’s a thing that keeps—

Keyframe: It obscures the truth in a way.

Thomson: Exactly. And if you obscure the truth long enough, you’ve done great damage. Good work is still done, and good work is its own reward, and often good work is quite well paid. Not always. But these little prizes, I think they are very damaging. And I think that the Oscars are part of a Hollywood that’s gone, and we should let it go. We don’t have movie stars in the way we used to, and we try to create them in a scandalous vein so that the wretched Lindsay Lohan becomes a sort of a new Marilyn Monroe—which is very unkind to [Lohan]. I don’t mean to defend her but she’s probably going to end up dead long before her time. And a lot of people will have made a fortune out of telling stories about her that nobody really cared whether they were true or not. The element of journalism in them was just—they might just as well have been made up. She’s an ongoing reality show, and it’s tedious and it’s very hard on her, and I don’t think it’s doing us any good at all.

Keyframe: To bring it back to movies, let me rattle off the titles you’re showing at the Bristol Festival of Ideas in the UK, because I presume you chose them because of some power they retain on the big screen: Kiss Me Deadly, Breathless, The Truman Show and Blue Velvet. And at another stop, The Arbor.

Thomson: They’re all films that I talk about at some length in the book. Obviously the book is a certain length but it leaves out a mass of films, but there are some films I really do talk about. Kiss Me Deadly seems to me to be a film of the fifties that has not dated at all. It’s as current as it ever was, and as brilliant, and as frightening. Almost everything from that decade has dated, which is fair enough. This hasn’t, and it’s an inexplicable film. I still don’t know how it was made. It’s much, much better than anything else [Robert] Aldrich ever made. Blue Velvet? A masterpiece, I think. I accept that Mulholland Drive is another masterpiece, and I don’t know which is superior. But I think that Blue Velvet is marginally more accessible to audiences, so I’ll go for that. What were the other two?

Keyframe: Breathless.

Thomson: Well, Breathless is a film that changed the dynamic of cutting, and really began to change narrative in a big, big way. The other one is The Truman Show, and The Truman Show is, I think, the best movie portrait of the world of the screen taking over that has ever been made. The scene where Truman is trying to escape and he realizes that the sky is actually a screen, that’s a perfect image of what I’m talking about.

Keyframe: The Purple Rose of Cairo perhaps fits your thesis.

Thomson: Yeah. The Purple Rose of Cairo, one of the Woody Allen films I really love.

Keyframe: Then The Arbor takes us in a different direction.

Thomson: It does. The Arbor is a great film for the confusion of documentary and fiction. I would say it’s one of the best films I’ve seen in the last two years. I love it.

Keyframe: What I’m grappling with is that the way you and I watch movies, and will watch them until the end, is largely not going to change. Yes, we’ll watch a movie on a computer when we never would have once, but the values we have with respect to movies are pretty entrenched. And that’s true for everybody, however they arrived at them. The good news is that no matter the technological and cultural changes, we’ll always have Paris. We’ll always have our relationship with movies. Someone who’s in their 20s has a different relationship. I mourn that, but maybe I shouldn’t.

Thomson: I’m not sure you’re right. I think that our generation, my generation more than yours, no matter how badly I feel about what’s playing at the local theaters I have a better chance of putting more great films on my television screen than anyone’s ever had. You really do have access to the library of film. You’re seeing it in a very different way. You’re probably seeing it alone or almost alone, you’re seeing a certain-sized image, you can interrupt it, you can do a lot of things to it that you could not do when you saw it in a theater. But generations will pass, and die. It’s very interesting, I think there’s no one alive now who fought in the First World War. Now the First World War, in my childhood and growing up, was a huge cultural force. Just like the Second World War. But you have to face the fact that a time will come when nobody has direct experience of those things anymore. And I have kids who really do not think of movies in relationship to theaters. They think of movies in relation to smaller screens. And the theater experience will be forgotten. So, yeah, in the twilight of our dying light or whatever, we have it quite good. Whatever film you want to see tonight, you probably can. But not in the ideal form. You see it in a reproduced, reduced form. But that will pass, too.

Keyframe: Swing dance came back ten years ago. Maybe in twenty years someone will get the idea for a business model of opening up a theater and showing things on film. Kids will go, ‘Wow, we’ve never done this before.” I could see someone doing that.

Thomson: I can, too. For a year or two. I could see it happening.

Keyframe: David Woodley Packard’s heirs.

Thomson: That’s a very interesting example. Someone I know very well. He, with enormous generosity, brought the Stanford Theatre [in Palo Alto, California] back, so that it is as it was in the forties, and looks and feels like that and those are the films he likes to show there. And he has an audience. Surprising. Not Stanford students. It’s townspeople, and they’re of a certain age. And you don’t have to be brilliant to see that they’re not going to last another 10 years, and David Packard may not. And I don’t think David has a plan for what to do with that theater afterward. I don’t think any of his heirs want to take it on. And indeed, you couldn’t take it on unless you had David’s incredible devotion to it. It needs a kind of madness to do it. (Laughs.) So I don’t know what will happen to it. That happens to everything in the end.

Keyframe: Any last thoughts about The Big Screen?

Thomson: I hope people will find that it works as a history, but that they enjoy it as something personal and passionate and provocative and argumentative. That’s what I meant it to be. It’s really a book to stir people up and make them think a bit. It’s a book I feel proud of.

Keyframe: So you hope people argue with you a little bit?

Thomson: Always.