Three human figures appear in a desert, with sunlight piercing their surroundings. One member of the group, a man, is perhaps a guide for the other two, who form an aging couple. Peter Schreiner’s film Fata Morgana (2013) opens with these people, standing essentially still, having come to a new place (as the male member of the couple says) “to find a point of reference or of inner stability.” The film lingers on their faces as they think and talk about how to do so; images later appear of the couple’s members indoors in a farmhouse and outside staring at rocks and leaves, possibly around their home, potentially seeking that same point. The displaced people move between the film’s different locations—physically, psychically, and spiritually—in search of a peace that they might share.

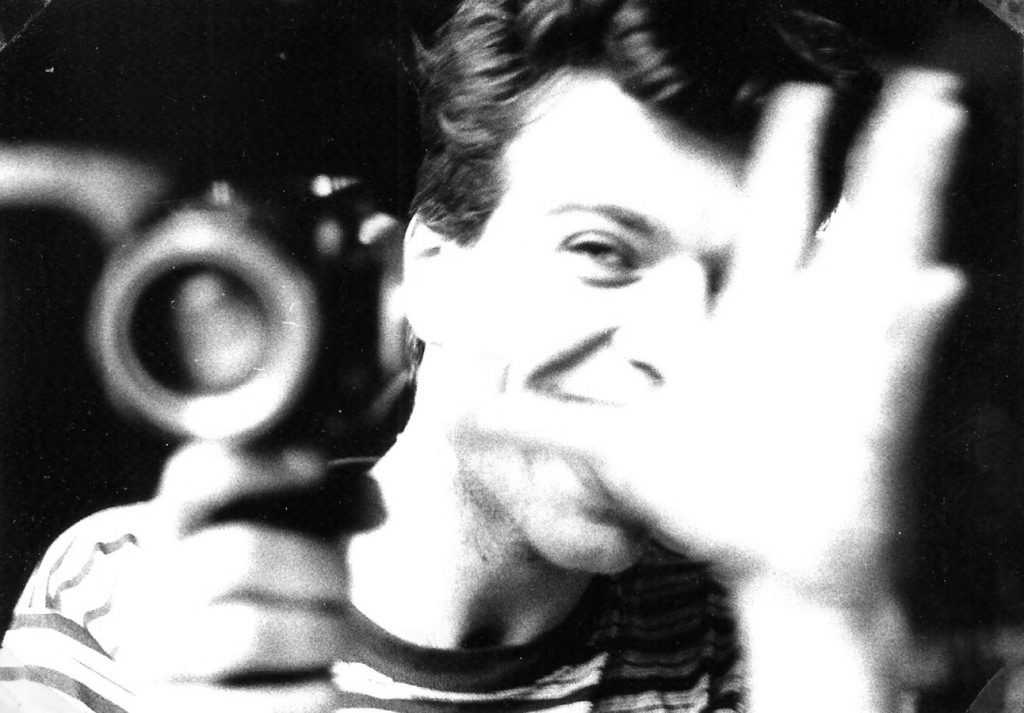

The journey forming Fata Morgana—which screens this week at the São Paulo International Film Festival—is photographed in strong black-and-white, bringing details of depth, texture, light, and shadow into sharp focus. So have nearly all of the Austrian artist Schreiner’s previous films, beginning with the aperture’s flooding open at the start of his debut film, Glaring Light (1982). The film featured the then-twenty-five-year-old filmmaker himself, as well as a number of friends and loved ones, in a collection of scenes of young people exploring Austrian and German cities in search of themselves. At several points people talk or simply laugh in close communion with the camera, building up to images of Schreiner and a friend lying on the grass after driving from Vienna to Kassel.

Glaring Light and Schreiner’s subsequent Only Love (1983) were poetic registers of the everyday, observing people from a comfortable distance as they found pleasure through the act of discovering their surroundings. Over time, the filmmaker’s journeys expanded while his focus sharpened. The central point of view in the travelogue On the Way (1986-90) is its camera’s, which regards an Italian mountainside and a sleeping infant with equal freshness and equal wonder. Everything that the film sees is examined closely, such that otherwise quotidian sights—a small, sentient group of trees, or a supine pregnant stomach rising and falling—take on a natural splendor.

Illumination has come throughout Schreiner’s cinema to apply even and especially to human faces, which Schreiner (acting as his own cinematographer and editor, even in past periods of poor eyesight) has increasingly explored as rich landscapes. Fata Morgana concludes a digital trilogy, begun after the longtime 16mm filmmaker took an eight-year hiatus from directing, in which Schreiner and another person or small group of people explore surroundings new to them. In Bellavista (2006) and Totó (2009), a woman and a man respectively return to the Italian villages of their births after long periods of separation from them, such that they find the old places to be deeply unfamiliar; in Fata Morgana, the people similarly seem to be discovering many of their surroundings for the very first time; and in all three films, the camera studies the lines and grooves in its human subjects’ faces, settling upon an enlarged eye or nose for a while as the person breathes silently and thinks.

Schreiner’s films have much in common with those of his two key filmmaker references, Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni. Like them, he has moved over time from initial neorealism to eventual psychological realism, shifting deeper into focus on human bodies in search of guarded souls. Schreiner has done so in close collaboration with a consistent team of offscreen collaborators—including his wife Maria and two adult children—as well as a small number of regular actors, whose evolving presences from film to film create a narrative of people changing over time. Though the Libyan guide in Fata Morgana, Awad Elkish, is new to Schreiner’s films, both members of the couple have previously appeared in them. The pockmarked man, Christian Schmidt, emerged nearly thirty years prior from among a group of young friends and their family members enjoying each other’s company in Children Film (1985); the richly wrinkled woman, Giuliana Pachner, searched with wide, uncertain eyes through the resort area of her provincial native town in Bellavista.

Fata Morgana presents many isolated images of each lover as he or she considers new surroundings, as well as a few precious moments of the pair united, whether touching foreheads intensely or simply sitting by each other’s side. Throughout, one senses a patient offscreen observer keeping them and Awad close company. In the following monologue, created with Schreiner over e-mail, the filmmaker reflects on how Fata Morgana and other films present a lifelong journey taken in order to find oneself, undergone with fellow travelers.

Peter Schreiner: What is cinema?

Maybe:

A collective trip (over and over again begun) of euphoria, refused in everyday life, moving from passive exhibition of the bare being to an active breakthrough of self-representation in front of and behind the camera.

Or:

A movement (over and over again begun) of a flowing of these currents into each other and the impulse of transition between them.

A projection from outside to inside to outside.

The riddle of time.

The riddle of impenetrable surfaces.

The riddle of (thereby released) thoughts, feelings, and spiritual movements.

And cinema seeks:

To share these riddles.

To share life with many (utopia: with all people – what a claim)

To be understood (what presumption)

I have enjoyed to the full, rather, the opposite:

Tension and letting loose

Learning and also forgetting things over the years.

Cinema mediates and annuls time (I believe that I know this)

Such that the timeless things remain.

But what remains already?

Maybe only the present moment remains

frame for frame, always anew.

As I have made films I have experienced, over and over, that projects grow by themselves out of life. Fata Morgana originated from chance. I never had the intention to travel through the desert, let alone to shoot a film there. I would not have been there at all were it not for the invitation of my Libyan friend Awad Elkish, a city-dweller in Tripoli, to introduce my family members and me to his desert, the place of his longing.

Maybe also at the beginning there stood the travel story of Giuliana Pachner, who had once, several years ago, been sent on the run from the narrow-mindedness of her village to the Italian island of Lampedusa, on whose shores many refugees had already run aground.

A certain feeling of groundlessness, in fact, inflicted all of us: my friend Hermann Krejcar’s sensations of homelessness, my friend Christian Schmidt’s feelings of having lost the impartiality and instinctiveness of his youth, and my own fears, my own isolation, my own crises.

Crises make films. This is my age-old experience. All my films are marked by crises, born from crises, sometimes even released them. To me, it is clear: In order to film, one must dive into crisis, or better yet, to dive through it, and find a way to new shores.

If I invent a beginning to my work, in which I produced my first proper film, Glaring Light, in 1982, then it would mean that my beginning came at the same time as the ending of one of my most intense crises. It was characterized mainly by passiveness and mental isolation throughout school years, by desperation, feelings of inferiority, lovesickness, and a darkness that enveloped everything. I was reaching the point of not even being able to look into other people’s faces, and instead when I spoke to them I looked at the ground. My cinematic experiences had narrowed from a short euphoric period at their outset into a desperate hide-and-seek behind the technical equipment. I did not hide freely out of power cravings, but rather ravenously in search of human contact, for someone into whose eyes I could finally look.

Glaring Light became a sort of emergency program for me. I had to make it. Above all, I had to make it in such a way so that it would become what it wanted to be, without deducing or considering how it would work on other people. The film’s title itself indicates how the work was my act of self-authorization. For me cinema posed the only possibility through which I could express my oversized longing, and through which I could share all the lives that I saw and felt inside myself with others.

Hermann, who played the main character in Glaring Light, had lived with me for some time, and we agreed to shoot a part of the film together, with him in front of the camera and me behind it. Once we had finished preparing ourselves for the shoot, however, he told me that he absolutely had to travel at that instant to the German city of Kassel, about six hundred kilometers from Vienna, to visit the art fair documenta. My answer was that I would go with him. And so we did.

I felt instinctively that the work could succeed only through a strong formal reduction and a clear line of action set within the most obvious locations, both physically and psychically. Yes, we drove hundreds of kilometers in my father’s car from Vienna to Kassel, but once we arrived, the film became more important to Hermann than the art exhibition was. It did not seem at all necessary to go inside the buildings, and instead we stayed outdoors on the meadow.

If I look for the differences between how I did it then and how I might do it now, I will see none. Abstraction, not naturalism, is the strength of my films. I had to escape from technical accessories at the outset. I had to leave my place behind the camera and literally enter the scene in order to be able to enter my first true work, the first to become a part of me and in which I felt fine.

I used black-and-white then, as I have for all my subsequent projects, which has helped me to reduce and find abstraction. I moved from celluloid to digital after taking an eight-year break from filmmaking, between 1995 and 2003, at the encouragement of my friend Hubert Sauper, who urged me to try a new beginning. Through digital I have found the possibility to work more economically, more independently, and with greater precision, such that there will be no step back to analog.

After thirty years of creation, I am both the same and different. I am still able to inhabit my films, but I can do this now without having to step in front of the camera. The endeavors for self-authorization now concentrate upon the protagonists in front of the camera, and upon the film’s viewers. Even more radically than they used to, my films search for closeness, for stepping out of the observer’s role, for opening forward. My work lies in creating these spaces that can be entered by others.

Creation is possible to the extent to which I have mentally freed myself. To know and plan my work’s outcome in advance would take all the sense out of it. The work on Fata Morgana unfolded over nearly three years, and even the difficulties that arose internally during its creation helped will it into being.

The origin of the film concerns two concrete scenes.

At the beginning everything was possible. The film absolutely could have taken place on Lampedusa or in the “Dead Mountains” of lower Austria. Quite early, and among the rest of the events, there was Awad’s invitation to travel with him to the Sahara. Then the war and revolution in Libya made this journey impossible.

The Sahara settings used in the film come from a ten-day field trip with test images shot in May 2010. The main shoot was planned for 2011. However, one month before this journey’s beginning, we needed to cancel everything and find a new location. This new place could not be a substitute for the previously planned place, as we had already formed an emotionally intense relationship with the Libyran Sahara. Moreover, it would have been intolerable to make a film in a neighboring country with the knowledge of our friend Awad and his family in mortal danger, unable to flee.

We arrived in Lausitz, a district in East Germany, and after a one-week search my wife Maria and I found suitable places for the project’s continuation. The devastation of natural and cultural spaces as caused by brown coal open-cast mining, leading to immense so-called “empty places” directly in the middle of Europe, seemed to clearly represent our resource-destructive Western lifestyle, which Nature was only slowly making an effort to reclaim. As both a main shooting and residential location we found an abandoned farm situated in one of the quarrying areas with a fate already sealed: There would soon open up an abyss of about one hundred meters deep into which the house, woods, meadows, and fields would simply disappear. All of which might seem bad to us, by the way, but for the native population in that place this has been a part of life for several decades.

I don’t think that the question of location has a greater or different meaning in Fata Morgana than it has in my other films, though it might seem to at first sight. Locations are basic conditions for me, as are the particular life moment of filming, the period of time available for it, the weather during that period, and the instantaneous sensitivities of everyone in front of and behind the camera. We all bring psychic luggage with us into the scene.

At the start of the shoot for Bellavista (2006), for instance, I often had to wait many hours until Giuliana was ready to work with me. Even though there was instantly a familiarity between us when we met for the first time in her home village of Sappada, it wasn’t easy for her to appear in front of a camera. She had never had the experience before, and I think that it was a great challenge for her. If we then set out, we did not know to which place in the village and their surroundings our way would lead us. Very often these were in-between sites—places of retreat that Giuliana had visited in her childhood, or more often, indefinable empty places between two concrete venues. In order to film, we could take these un-places and start anew with them.

Places that have never previously been entered offer many unusual new points of view, all reflected by the presence of the film camera, which legitimizes one’s stay. For me this is always a kind of action-taking specific to cinema, which pushes us away from everyday life in order to set us up in an absolutely new situation that stimulates us and challenges our creativity. Here, at these unknown places in between those of the everyday, and with a sufficient credit of time, the necessary devices at hand, alert senses, and enough serenity, the abstraction process of making cinema can begin.

I have discovered in my experience and understanding that the truly cinematic locations nearly always show the basic character of what appears to be an empty space, a sort of un-place or wild site. Such are the places that can be made habitable by cinema. I believe that this has something to do with cinema’s talent for abstraction. It is through filming that everyday places receive a sort of wild character and become clearances as cinema releases them from a number of things: From contexts, from meanings, from history, at last from what we are used to calling “reality,” and give them a fictive character through which they can handle all these things better.

The cinematic glance is momentary in the full sense of that word. The impartial glimpse of the camera generates a sort of new reality that is only very loosely connected to the reality of the film shoot. A sort of emptying-out takes place: The technical circumstances of camera and microphone effectively and selectively register an effigy of the phenomenon of reality. When we watch a film, this effigy works on our feelings and on our powers of reflection. I think that this process is the heart of cinema.

The question of the specifically visible physical location is therefore, for me, a question of circumstantial, subordinated meaning. The states of consciousness, feelings, and associations that a place can generate in a person are vital, and they can hardly be planned or foreseen. Although I always write a long concept at the beginning of a film, as a sort of starting point, the dialogue is not included, and the film’s ideas change greatly during its shoot. We shoot for over an hour at a time without taking a break, and this allows the actors to go deep into the situation and generate the words themselves. What you might call “story” is the result of a long process (years-long, in the case of Fata Morgana) of intensely following a trance state through staying and working at different locations.

To know with whom one is jointly traveling, and know him or her well, is essential to doing this. For example, I knew Antonio Cotroneo, the lead actor of my film Totó (2009), for a quarter-century before we filmed together. Over the course of two years we traveled many times to his birthplace in southern Italy, where he showed me unique places and people. However, it was not until after the first year that we arrived at the film scenes.

This process was, for both of us, a trip into the depths of our emotions, fears, and longings, getting closer to concrete places in order to become impartially involved with them. Antonio had not entered some since his early childhood, while others he had only passed by before then. Some places counted as his secrets, almost as though they were concealed within him. Under the protection of the camera we could visit them together, as questioners, not as knowers, and open to whatever would happen.

Similarly, over the passage of time in my work with Giuliana, I have noticed her taking more and more pleasure in our trials. One day while we were making Bellavista I saw that she had finally left her passive situation of simply being filmed and become, step by step, really an active protagonist. In Fata Morgana she is even more so. It has thus been a great, evolving experience for the two of us in our collaboration, which includes a third film that we are finishing next year.

I could not work in this way with people to whom I did not feel great nearness and attachment. This is quite an important requirement for me in films. If the apparatus not used in an attempt to create an objectivizing authority system, but rather brought into the greatest possible closeness (including psychically), then it can help us to track down forgotten and concealed information within our own depths. It allows us to share our secrets without disclosing them.

These exchanges can form a dangerous balancing act. When we were shooting Fata Morgana we often met deserts more intense in farm rooms and in our own reactions than anywhere along the Sahara’s sands. It was life itself that led us into the desert, and we had to rely upon one another as we explored it together.

I find allowing for life, and for its unpredictability, to be essential to the process of filmmaking: It allows one to be led to true people, to true situations and locations. Making films for me mainly means being led into unknown places. I am never embarrassed by my ignorance, nor am I by my discoveries. Cinema is able to emphasize the strange for me in every place, to clarify my gaze and open it onto a new world.

I make films first of all for myself, while still believing that people are very similar at heart. Of course, the search for kindred spirits seldom actually succeeds, but I still think that it is important to always keep in mind this utopia.

Thanks to Christoph Huber for research help.

Clips from Peter Schreiner’s films, including Fata Morgana, can be viewed on YouTube. More information can be found at the artist’s website.

Aaron Cutler works as a programming aide for the São Paulo International Film Festival and keeps a film criticism site, The Moviegoer.