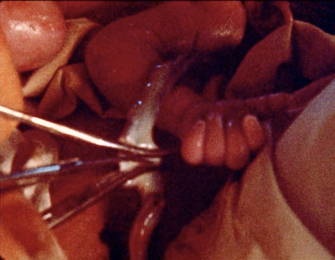

Scene from MISCONCEPTION.

The films of Marjorie Keller are politically bracing and formally deft, and even though her reputation within both avant-garde cinema and the history of feminist filmmaking has only continued to grow since her untimely death in 1994 (at the cruel age of 43), her work still ought to be much better known than it is. In some ways, speaking of experimental filmmakers of greater or lesser “fame” is an exercise in relativism bordering on the absurd, since arguably no one in this vital corner of cinematic art has received their due. (The greatest avant-gardists, such as Maya Deren and Stan Brakhage, remain obscure when compared to even the worst Hollywood filmmakers of today.)

But Keller presents an interesting case. Within the small coterie of filmmakers and presumed tastemakers who, some have argued quite vociferously, have shaped the mainstream canon of avant-garde film in the U.S., Keller should have been in the ultimate position of privilege. Her husband until the time of her death was P. Adams Sitney, Princeton professor, author of the classic text Visionary Film, and, in the minds of some, the Clement Greenberg figure of American experimental film, a canonizer and a shaper of the main throughline of the dominant history. However, this did not help to place Keller in a central position vis-à-vis the New York scene.

Her work, while lyrical and handcrafted in terms of its visual construction, tended to give as much weight to sync sound and the diegetic event—often political, particularly with an emphasis on women’s criticism of the domestic sphere. This orientation did not coincide with Sitney’s primary historical narrative, which emphasized phenomenological revelation and a Romantic fixation on consciousness as a tragically compromised event. For Keller, “consciousness” was a material event, and it could be raised.

By the same token, the academic feminist film studies of the ’70s and ’80s, which could have gleaned so much from Keller’s filmmaking, could not welcome her into its canon (which in retrospect was rather narrow). At the time, some found avant-garde filmmaking elitist in and of itself; others thought that Keller’s influences (Brakhage, Marie Menken) did not admit of the kinds of psychoanalytic analysis (Freud and especially Lacan) that certain feminist academicians considered the advanced frontier of filmmaking and film scholarship. Keller didn’t think she was missing much. Her feminism was decidedly materialist and grounded in the everyday, not the deep structures of the unconscious.

Keller’s 1977 film Misconception is both her longest single film (43 minutes) and in some respects her most complex. It has been cited over the years as a “feminist rejoinder” to Brakhage’s film Window Water Baby Moving (1959), the classic film he made from footage documenting his wife Jane giving birth to the couple’s first child. The silent, nonlinear film, it has been said, lyricizes and idealizes childbirth, partly because Brakhage was processing it from his male point of view.

P. Adams Sitney’s primary historical narrative emphasized phenomenological revelation and a Romantic fixation on consciousness as a tragically compromised event. For his wife, Marjorie Keller, ‘consciousness’ was a material event, and it could be raised.

But Keller, an avowed acolyte of Brakhage, has a different but related project. Misconception is a six-part film that follows a friend, Chris, late into her pregnancy and eventual delivery by natural birth. Keller’s more expansive timeframe, her use of sound (including the mother admitting she might not have had children if she’d really known how hard parenting is), and her integration of diary film technique with jagged, associative editing, make Misconception much more of an experimental documentary than a straightforward avant-garde film. Perhaps this hybridity explains Keller’s uneasy positioning in the history of her chosen medium.

Misconception is not a linear film. Keller employs contrapuntal sound and disjunctive editing in order to create what Peter Kubelka called “sync events,” new audio-visual conjunctures that mutually reconfigure one another and form a third, unique material entity. For instance at the start of Part 2 we see the mother-to-be in a bathtub while we hear screams of agony and distress from the childbirth to come. The soapy form of her “baby bump” is aligned with an inarticulate, primal fear. Later in this sequence, Keller employs staccato, nearly frame-level editing to thrust discontinuous times and spaces into this bathtub scene.

Starting at 6:20, we see Chris and her older son in the tub together enjoying a playful bath. Keller’s extreme close-ups zero in less on the two people than on the texture of their skin, their points of contact, the dark folds of their bodies, and in particular Chris’s swollen breasts. Without the highly quotidian character of the soundtrack (“You wanna take a bath? You wanna drink water?”), Keller’s footage would approximate Brakhage’s style of abstraction from the domestic scene.

Then, at 6:14, we see the first of several intrusive edits. They are quite visible, and insert imagery with a very different color and texture. Eventually this secondary material displays doctors and nurses in scrubs, the close-up face of a newborn, and pure dark flash-frames of the interstitial, unoccupied moments in the footage that capture the overall environment of the upcoming birth. In time, Keller mixes the flash-frames, playing them like a selection of contrapuntal notes—Chris walking around in her hospital gown, the blinding orange of her partner’s shirt (emphasizing, as much of Misconception does, the unavoidable positioning of the father as outsider to the event of birth), and some passages of scratched, pockmarked film leader.

These edits, wherein Keller makes the physical disruption of the tape splice as obtrusive as possible, recall the more contemporary works of Luther Price, who similarly turns the intrusion of one image or one piece of celluloid into/onto another into a kind of violation. Throughout the excerpt, Misconception works to contrast both the beauty and the easy togetherness of mother and son in the bathtub with the future moment that will make this situation, this beauty, possible. Like Brakhage, Keller elaborates a complex situation using cinema’s capacity for vertical time arrangements. But unlike Brakhage, Keller maintains a concrete relationship to the mother’s lived time, rather than delving into a more psychological (or psychoanalytic) realm of memory or reverie. While the title, Misconception, may seem to imply that Keller meant her materialism as a corrective to an error, the actual film tells us otherwise—that concrete experience is the basis for our thoughts, and that the physical engagement with that lived experience, when treated rigorously enough, can achieve a lyricism all its own.