One thing that must be said of the hagiographical enterprise titled Salinger: filmmaker Shane Salerno has left few pebbles unturned. For though Jerome David Salinger (1919-2010) may have during his lifetime published but one novel, ten short stories and four novellas, this scant resume has formed the basis for cult-like adulation that shows no signs of abating—and that Salerno’s film was expressly designed to stoke. The thought that can’t help but hover regarding both the man and his work—both far from uninteresting sociologically, aesthetically and ethically—is that J.D. Salinger leaves much to be desired.

Clearly Salerno doesn’t think so, and neither do the notables he’s assembled to speak of the man and his work, including A. Scott Berg, John Guare, E.L. Doctorow, Tom Wolfe, Judd Apatow and Tony Bill, plus two women who knew him more personally: Jean Miller and Joyce Maynard. Cleverly utilizing still photographs and newsreels and wrapped in an oppressively melodramatic score by Lorne Balfe, Salinger is a pluperfect example of what critic Manny Farber called “The Gimp.” Part of a woman’s gold outfit in the Victorian era, “It was a cord running from the hem of skirt to waistband; when preparing to hit the ball, you flicked it with your little finger and up came the hem. Thus suddenly, for a brief instant, it revealed Kro-Flite, high-button shoes and greensward, but left everything else carefully concealed behind yards of eyeleted cambrie.’ That’s Salinger—an intellectual peepshow, much like its subject. For J.D. Salinger’s story is a search for “wisdom” producing not a sage but a “control freak.” We’re given a glimpse of “everything” and the result is nothing special. Just another neurotic, albeit one with some degree of literary talent, lucky enough to come equipped with a cheering section that has stood him in good stead throughout his life and now doubtless well beyond the grave.

Born to a well-to-do family, Jerry Salinger began writing while still in prep school. His first works appeared in Story magazine in the early forties. But, as Salerno shows, his goal was The New Yorker—and he reached it in 1948 when he wrote “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” the tale of voluble young man named Seymour Glass who leaves his self-absorbed wife to converse with a four year-old girl on a Florida beach before returning to his hotel room to shoot himself in the head—much like Edward Arlington Robinson’s “Richard Cory.” Salinger would devote the better part of his career to writing about Seymour Glass and his family—clearly sensing he’d killed off an interesting character too soon. But prior to that he wrote the book that made him—as Neil Patrick Harris would say—legen (wait for it) dary(!), The Catcher in the Rye.

Published in 1951, Catcher has sold some 250,000 copies a year ever since. This is surely indicative of some inarguable quality. But it also underscores how successful one can be telling people precisely what they want to hear. The book’s hero, Holden Caulfield, is a prep school student playing hooky in New York. Roaming through locales and encountering individuals both “high” and “low,” Holden is desperate to get laid. This is hardly an uncommon pursuit of the young. But Holden is quite ambivalent about the loss of his virginity, fearful of what the adulthood it represents portends. Said adults, and anyone else who meets with his displeasure are deemed by him to be “phonies,” deserving of (to put it most politely) “Termination with Extreme Prejudice.” The climactic “phony” is Holden’s beloved English teacher Mr. Antolini, whose home he repairs to at the last. Antolini offers our hero advice on life, numerous cocktails and a place to sleep— said sleep being interrupted when Holden finds the teacher patting his head in a way that he regards as “flitty.” Heaven forbid!

Decidedly un-phony is Holden’s younger sister Phoebe—who like the child in “A Perfect Day for Bananfish” embodies the “innocence” and “purity” Salinger saw as the unique province of the young and female. Holden believes himself to be the protector of all such tykes in a fantasy involving his mishearing of the song “Comin’ Through the Rye” as “Catcher in the Rye.” He pictures himself as the guardian of a group of children playing in a rye field on the edge of a cliff, his job being to catch them lest they fall off it. Will Holden and Phoebe fall off? Salinger leaves that question unanswered, thus inspiring constant requests for a sequel.

This tale of youth in crisis on the brink of adulthood has not only won an enormous public following but quite understandably attracted repeated offers for a film adaptation of notables as varied as Billy Wilder, Elia Kazan and Jerry Lewis. But Salinger (who claimed at one point, one presumes facetiously, that only he could play Holden) resisted them all, having been disillusioned by the fate of his shvoiort story, “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut,” produced by Samuel Goldwyn as My Foolish Heart in 1949. Though the screenwriters were Julius and Phillip Epstein, whose Casablanca Salinger adored, this rendition turned “Uncle Wiggly” into a sentimental wartime romance that pleased few and enraged Salinger, who doubtless chafed at seeing his young heroine portrayed by an adult female, Susan Hayward, and vowed that Hollywood would never get its hands on his work again—particularly Catcher in the Rye. There was however Igby Goes Down, writer-director Burr Steers’ incredibly witty 2002 variation on Catcher, in which Macaulay Culkin’s remarkably talented brother Kieran stars as prep school delinquent on a New York spree, unencumbered by sexual anxiety, homophobia, sentimentality or any sort of fixation on underage females and their presumed state of grace.

‘Igby Goes Down’

As you can see that when it comes to youthful zeitgeist, Steers has Salinger beat by a country mile. But there’s another reason for keeping Catcher off the screen and that has to with the murderous havoc it’s inspired. Worshipful of its subject though it may be, there’s no way Salerno can avoid mentioning Mark David Chapman, who on December 8, 1980, shot and killed John Lennon sending a handwritten statement to the New York Times urging everyone to read The Catcher in the Rye, calling it an “extraordinary book that holds many answers.” In March 30, 1981, a Catcher enthusiast named John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in order to impress actress Jodie Foster—who he saw as his Phoebe Caulfield. Then in October of 1991, one John Robert Bardo shot and killed actress Rebeca Schaerffer, apparently as a result of what he saw as her inability to live up to Salingerian standards. It’s been awhile, but there’s no reason to suspect that this reign of literary-inspired terror won’t kick up again.

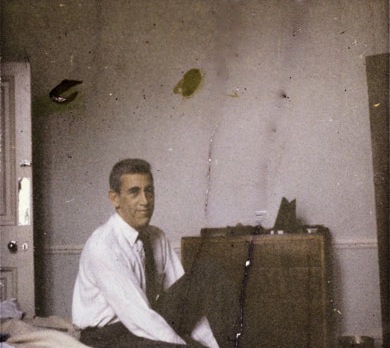

I suspect this is why Salinger wisely refrains from dramatizing Catcher. But it does deal quite extensively with its author’s actual life. We’re treated to the tale of his passion for Oona O’Neal, the daughter of the great playwright Eugene O’Neill, who Salinger lost to none other than Charlie Chaplin. Salerno shows us many stills of Oona at her most dazzlingly young and gorgeous, but it doesn’t mention her close lifelong friend Carol Matthau who in her wittily malicious memoir Among the Porcupines makes derisive reference to “Little Jerry Salinger” and how tiresome she found him. This is most amusing as Salinger was physically quite tall in stature.

Quite fascinatingly Salinger uncovers the fact that the writer’s first wife, Sylvia Welter, to whom he was married from 1945-1947, was a Nazi. An unwary Salinger learned this too late, and ended the marriage. His second wife Claire Douglas, to whom he was married from 1955-1967 is a sad tale of a different sort. Like so man of his romances she began as an inspiration—a juene fille en fleurs—only to end, two neglected children later, as a wife shut out from a man who preferred the shack in which he was heard typing away at something or other to contact with any living soul, fled. Her eventual replacement, Colleen O’Neil, arrived in 1988 and stayed though to the very end. But it’s the testimony of one who came and went in between—Joyce Maynard—that is the most interesting. Salinger contacted Maynard when he saw her picture on the cover of the New York Times Sunday Magazine. She was the subject of an article about promising young writers. But as Maynard eventually learned, Jerry wasn’t interested in her writing at all – just in her as yet another image of youthful female “innocence.” When she dared to assert herself, it was all over. Maynard offers the film’s most dramatic moment as she recounts the scorn he heaped upon her, declaring she “loved the world”—apparently an unpardonable Salinger Sin. She also learns that there were a great many other young girls Salinger was courting in and around the same time, few of whom had anything artistic about them (the last Salinger wife being one such).

Salinger was reportedly ten years in the making. One doesn’t doubt this from the way it deals with figures both major and minor and its climactic revelation of a “Preview of Coming Literary Attractions” that the foundation he created plans to release over the next few years. While many of us imagined that inside that shack Salinger was engaged in something along the lines of this:

‘The Shining:’ ‘All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.”

He was in fact hard at work actually writing. Therefore what we shall see in the near future, Salinger promises is (1) A Counterintelligence Agent’s Diary, a book based in the counter-intelligence division when he interrogated prisoners of war during the final months of WWII; (2) A World War II Love Story dealing with that Nazi collaborator first wife; (3) A Religious Manual dealing with Salinger’s adherence to Vedanta; (4) five new short stories about Seymour Glass included in a complete assembly titled The Family Glass (which Salinger claims will be his crowning literary achievement) ; (5) The Last and Best of the Peter Pans, a new Holden Caulfield story, that may well be the “sequel” to Catcher the Salingeristas have been longing for.

While Salinger regards its hero’s interest in Vedanta as some new and original thing, it should be pointed out that the literary light most associated with this religion has been Christopher Isherwood, a writer whose mode and manner is precisely the opposite of J.D. Salinger’s. His Vedanta and the Western World is an extremely useful and quite modest guide.

But modesty isn’t Salinger’s strong suit. For if this film is to be taken at its word and image, World War II was won single-handedly by one Jerome David Salinger, who appears Forrest Gump-like on D-Day,the Battle of the Bulge and the opening of the Nazi death Camps. This may all be true, but the “Kro-Flite, high-button shoes and greensward” the “gimp” revealed were “true,” too.

And now to sing us out, Tony Bennett, accompanied by the equally great Bill Evans, with the title song of the film Jerry Salinger so loathed, music by Victor Young and lyrics by Ned Washington.

“My Foolish Heart,” Tony Bennett and Bill Evans

I for one find this Washington’s lyric more poignant and precise than anything Jerry Salinger ever wrote:

“There’s a line between love and fascination

Hard to see on an evening such as this

For they give the very same sensation

When you’re lost in the passion of a kiss.”