Movie stars are all unique in their own way, or at least so we assume. But really there are rather few who played roles and had careers unimaginable for anyone else, due to the singularity of their personality, looks, ethnicity and other factors during a particular era.

Today nobody really cares about the genetic makeup of multiracial stars like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson or Vin Diesel. But back in the day, conspicuous racial roots meant everything—consigning any talented actor who couldn’t “pass for white” (as several vintage Hollywood stars purportedly did) to careers portraying supporting, often comedy-relief stereotypes. Or occasionally to leading roles as “exotics,” darker-hued seducers, temptresses or sidekicks who almost invariably had relatively short-lived acting careers. (Whereas white actors who could “pass” in yellowface, brownface or redface often flourished for decades, their occasional multiethnic roles taken as proof of versatility.)

In pre-Civil Rights Movement days, that racial double standard severely limited the screen opportunities for such enormous talents as African Americans Paul Robeson and Lena Horne. Other ethnicities fared even worse; on those rare occasions when Hollywood made a film entirely revolving around Asian characters, for instance, the makeup department was simply let loose on some bankable Caucasian stars.

As a result, there’s no underestimating the exceptional case of Sabu, who died exactly half a century ago, yet remains the only Indian national to have achieved—for a time, at least—true international stardom from these shores. He may have become more of a cultural footnote than a legendary figure since then, but while some of his films may seem antiquated now, the qualities that endeared him to audiences are still vivid. He was, and is, an appealingly natural screen presence.

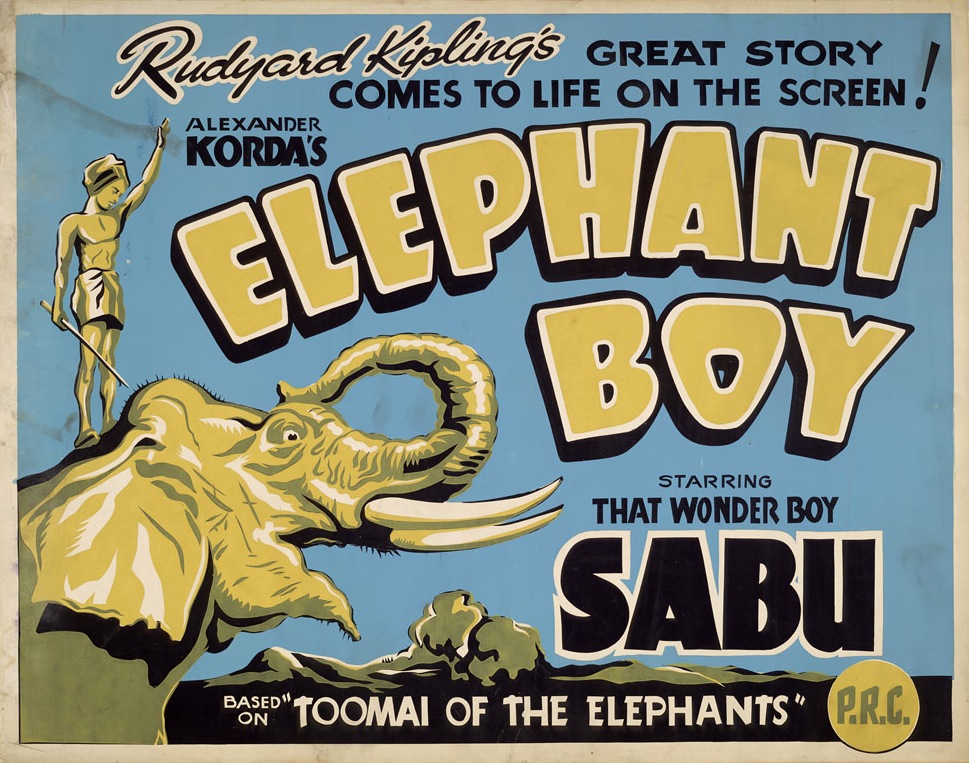

That he became an actor at all is something of a miracle. Leading British producer Alexander Korda was looking for a lead for his Kipling adaptation Elephant Boy, an unusual collaboration between his director brother Zoltan and documentarian Robert Flaherty. While the latter was shooting nature and location footage in the southern Indian kingdom of Mysore, he stumbled upon eleven-year-old Selar Shaik—an orphaned real-life “elephant boy” who tended the pachyderms owned by the local maharaja. Though the boy didn’t speak a word of English (he spoke this first role’s dialogue phonetically)—nor had he ever even seen a movie—he had such a winning personality that Korda and company realized they’d hit the jackpot.

When Elephant Boy hit theaters two years later, in 1937, critics and audiences agreed: Sabu (as he was now called) was that then-rare kind of child actor who’s charming because he never seemed to be “acting” at all. He was effortlessly energetic, athletic, sincere and ingratiating. The film was a hit, and instead of a one-shot novelty it launched a bona fide star.

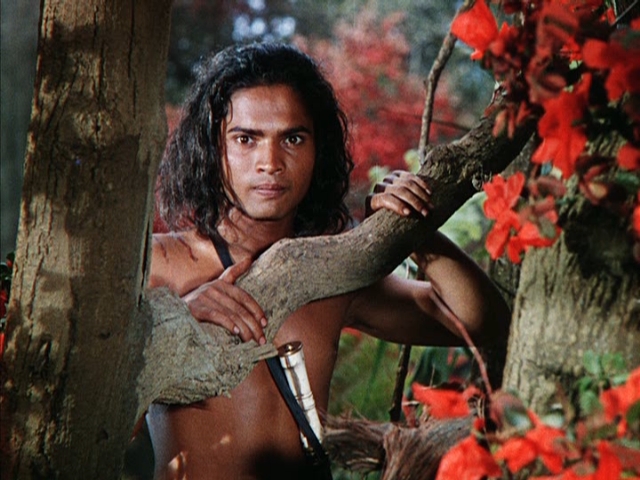

Sabu moved with his brother to England, where Korda built a series of big-budget color spectaculars around him: As an Indian prince in 1938’s Drums, a film whose gung-ho colonialist attitudes haven’t aged well; as The Thief of Bagdad, a global fantasy smash that compares quite well with the silent Douglas Fairbanks Sr. classic; and as Kipling’s Mowgli, the boy literally raised by wolves in Jungle Book.

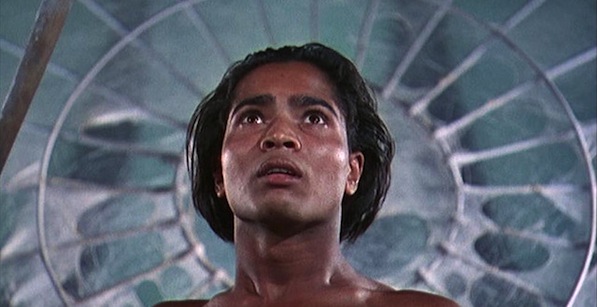

These were all among the most elaborate British productions of the era. The latter two, however, were filmed in the U.S.—as England was now at war, shooting there was deemed too risky. Naturally Hollywood expressed interest in this young star, now no longer a boy but a handsome, strapping young man. (Aside from a Tarzan or two, probably no mainstream actor ever spent as much screentime shirtless as Sabu.) For his part, he found Southern California much more pleasant than cold, rainy England. When Korda returned home, Sabu stayed behind, accepting a contract with Universal.

In a sense, it was the right place for him. The studio was then in the middle of its own color fantasy-adventure cycle, most starring the definitely “exotic” siren Maria Montez, a convent-educated bombshell from the Dominican Republic. One doubts the nuns would have approved of her scanty costumes (or scantier acting skills), but wartime audiences enjoyed such purely escapist exercises as Arabian Nights, White Savage and camp classic Cobra Woman—to name just the ones Sabu was in.

They didn’t do a great deal for him, though. Too genuinely “ethnic” to be deemed appropriate romantic interest (that task usually fell to the equally shirt-resistant Jon Hall), he played brave supporting-peasant-lad roles. Unlike Korda, Universal never seems to have even considered building films around him. Instead, they steadily if inadvertently diminished his stature.

Upon becoming a U.S. citizen at age twenty, Sabu promptly volunteered for military duty, and was eventually awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross for his service as an Air Force tail gunner. That high distinction won him few favors in post-war Hollywood, however. After one last film with the rapidly-fading Montez, Tangier, he had to return to England for the best role of his adult career: As the young aristocrat intrigued by Western ways in Powell & Pressburger‘s 1947 classic Black Narcissus. But the moments of charm and levity he provided were simply sidebars to a study of sexual repression amongst English nuns in a remote Himalayan convent (albeit one shot entirely on a U.K. soundstage). He was billed sixth.

After that, his career sputtered with an ebbing lineup of B-grade action flicks, designed for the lower half of double bills. They were exactly as classy as titles like Man-Eater of Kumaon or Sabu and the Magic Ring suggest. (There is, however, something to be said for having enough cache to get your name in the actual title.) Some were fun, some just inept. On the fun side, there was the likes of 1949’s well-crafted Columbia release Song of India and the nifty subsequent independent production Savage Drums.

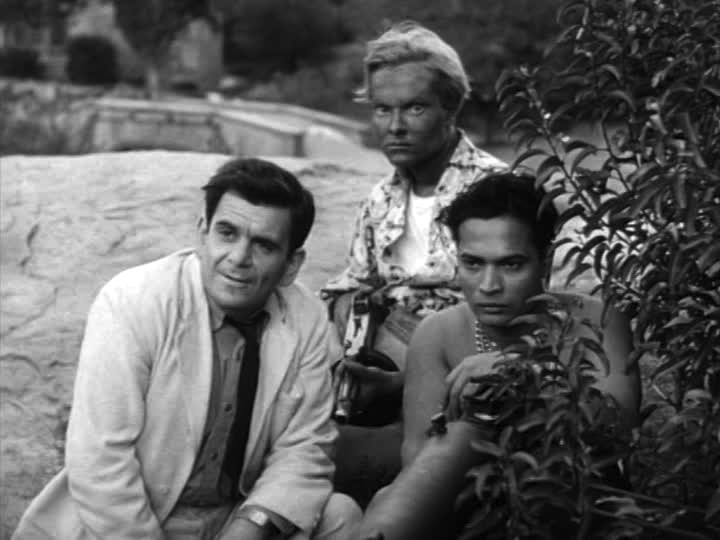

In the latter, Sabu plays Tipo, a professional boxer who returns to his tiny, fictive Pacific island nation after his ruling brother (its king) is assassinated. (Ironically, in real life Sabu’s own manager-brother was killed by robbers at the furniture store they co-owned. And even more eerily, the villains in the film try to kill his character by inducing a heart attack—exactly what felled the star at an incongruously early age.) This being 1951, the evildoers are of course scheming dirty-rat Communists, determined to thwart the country’s material and democratic advancement. A full-on foreign invasion ensues, thwarted by guess-who and pals.

As usual the only actual Asiatic actor in the cast, Sabu brings his customary poise and integrity to prolific “Poverty Row” director William Berke‘s polished little Red Scare thriller. Oh, the delights of yesteryear’s air travel: When the shite hits the fan, one of Sabu’s comedy sidekicks (lanky halfwit “Tex,” played by Bob Easton, who in real life had a near-genius I.Q.) pipes up “Ah’ll go git muh tommy-gun!” Which of course he’d brought as a carry-on.

Another fun one is 1956’s Jungle Hell, the first and last feature directed and written by Norman A. Cerf, who found more success as an editor. He actually edited it from footage shot for an inexplicably unsold Sabu-starring broadcast series. (It was distributed on the bottom half of a grindhouse double bill with the re-released Savage Drums.) He plays an Indian villager who defies the powerful local witch doctor by taking residents weakened by a radioactive “burning rock” to a Western doctor’s makeshift clinic.

While much of Jungle Hell‘s impressive animal scenes—most involving elephants—are stock footage (some shot for Man-Eater of Kumaon eight years earlier), it’s still baffling that this project didn’t win Sabu a second career on the small screen. Notably, one of his own children has a small featured role as an ailing child.

Sadly, Sabu left that son, a daughter and model/actress wife Marilyn Cooper (who’d appeared with him in Song of India) behind when he died in 1963, only thirty-nine years old. His fatal heart attack wasn’t just unexpected—it was near-inexplicable, as a doctor had purportedly just pronounced him in perfect health. It was especially tragic because, at that moment, things were looking up: He’d scored substantial supporting roles in two mainstream studio releases, the Robert Mitchum spy thriller Rampage and the next year’s live-action Disney feature A Tiger Walks (released after his death).

While he’d been dismissed in some quarters as representing an archaic Hollywood of movies trading in racial stereotypes, Sabu himself never seemed an “Uncle Tom.” His natural ease and dignity before the camera transcended all condescension and cliche. Aspects of nearly all Sabu’s films may seem corny now—but he’s never one of them.