“São Paulo is an amazing city to be filmed,” Brazilian filmmaker Paulo Sacramento writes by e-mail. “Even when it’s at its ugliest, you feel life pulsing through its veins. My debut feature Riocorrente (2013), which takes place in the city, is the result of many things that I’ve seen and felt and didn’t want to keep inside me anymore. The film is not a traditional narrative, but an emotional and sensorial experience whose primal energy I tried to harness.”

Sacramento’s elliptical ensemble piece, which focuses on three people in potential danger throughout the city, screened at this year’s International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) as part of the festival’s Hivos Tiger Awards Competition, consisting of 15 first and second features from around the globe. The Tigers—whose final prizewinners came from Japan (Anatomy of a Paper Clip [2013]), South Korea (Han Gong-Ju [2013]), and Sweden (Something Must Break [2014])—often get the most attention among the IFFR’s films. Yet even when the Tiger competition is at its best, the variety and quality of the sidebar programs are what make the festival special.

The largest project of artistic director Rutger Wolfson (who missed this year’s festival due to an autoimmune disease, and was subbed by supervisory board member Mart Dominicus) for the IFFR’s 43rd edition was a multi-strand program called “The State of Europe,” which placed several recent films in dialogue with one another to discuss the continent’s contemporary issues. They often did so with a deeply personal approach, one example being the film memoir What Now? Remind Me (2013, and due out in U.S. theaters later this year courtesy of The Cinema Guild). The film begins with its Portuguese director, Joaquim Pinto—a sound recorder and designer for great filmmakers such as João Cesar Monteiro, Raúl Ruiz, Werner Schroeter, and Rita Azevedo Gomes—living with HIV and Hepatitis C over twenty years after his initial diagnosis. He and his husband, Nuno Leonel, try to enjoy a life with their dogs in the countryside and live with memories of friends and loved ones over the course of a year.

“Europe seems an abstract concept,” Pinto and Leonel write by e-mail. “However, from our corner of it—a land of discoveries and passages—layers of past and present seem to overlap. Our film documents one full year of our lives immersed in today’s Portugal and Europe. Joaquim was going to participate in a long and difficult clinical trial with new drugs; we did not find any recent films dealing with this issue on a first-person basis, and thought that sharing our experiences could be of some use to others. Many people have the feeling that today’s society as a whole is a diseased body, so our story is just a small part of a larger one.”

What Now? Remind Me, which is narrated by Pinto, rails against the inadequacies of modern healthcare systems while surprising with flashes of brilliant color and music, hinting that Joaquim and Nuno’s troubles are enlarging their spirits. The film shows the couple seeking peace in the face of turbulence by finding pleasure in the everyday, with even potential annoyances like insects turning precious; what might otherwise seem like daily life’s irritations grow beautiful through open, close and patient observation.

Joaquim and Nuno’s goal of absorbing life’s riches by paying deeper attention to them was shared in the work of two great artists honored with retrospectives at this year’s IFFR. The first was the German filmmaker Heinz Emigholz, whose films were presented within the festival’s ‘Regained‘ section both as films in traditional screening rooms and as installations in the Het Nieuwe Instituut, an architectural studies center. Emigholz shifted away from fiction filmmaking nearly a quarter-century ago to make documentaries, primarily within a series called Photography and beyond that focuses on pre-existing works of visual art examined by Emigholz’s camera quietly and from different angles. A subset of the series called Architecture as Autobiography takes the life’s work of different architects as its starting points, with each film proceeding through an architect’s buildings in the order that they were built. Films like Sullivan’s Banks (1993-1999), Maillart’s Bridges (1995-1999), Goff in the Desert (2002-2003), and Schindler’s Houses (2006-2007) give present-day images of older structures to show how the architect’s spaces were originally used and how they are being used today.

“What happens to modern buildings in time?” Emigholz asked me last year in an interview for the webzine Idiom about his film Perret in France and Algeria (2012). “The originators, the first owners, leave them. New people move in, and the buildings change. . . .A lot of the buildings I have depicted are already forgotten, with only one building per architect taken to be the essence of his work. People rarely take the whole arc of his work, but I want to show how it began and how it ended.”

One senses wind blowing around the buildings that Emigholz photographs, people passing them, and an offscreen observer considering time’s passage. The autobiography in these works is double-tiered: The films serve as records both of what artists have left to the world of themselves and of the places that the filmmaker himself has seen and been. Throughout Emigholz’s films—including his precious and rarely screened fiction feature The Holy Bunch (1986-1990)—there flows a deep sense of melancholy, as though thoughts on what has been done and lost already were coloring thoughts on what might still be done. His architecture series will conclude with this year’s The Airstrip (2014); more films on different topics will follow.

The fiction films of IFFR honoree and Danish auteur Nils Malmros are autobiographical in a more traditional way. All but two of Malmros’s twelve features serve as thinly veiled fictionalizations of actual experiences that he’s had. The works travel from schoolchildren’s quarrels to struggles faced by adult filmmakers and neurosurgeons (a profession that both he and his father pursued) in a way that feels ineffably nimble yet emotionally precise. Malmros’s considerations are often moral as well as emotional. Films like Tree of Knowledge (1981) and Beauty and the Beast (1983) flood richly with light upon the looks that people give to one another, suggesting—perhaps above all else—how they choose to be cruel or kind.

“Malmros takes his own life as exemplary,” says critic-programmer Olaf Möller, who organized the retrospective with fulltime IFFR programmer Gerwin Tamsma. “No matter how extraordinary his circumstances have been, he is able to view them as ordinary, and relate something essential about life through the act of looking at himself in a gracefully interested way. He tries to look clearly to see what there is, humbly and without a trace of narcissism. Malmros considers his life useful for other people to see.”

This is especially true of his most recent film, the extraordinary Sorrow and Joy (2013), which moves from shock to reflection upon how people might learn to treat one another. In the 1980s Malmros’s wife Marianne, a small-town schoolteacher, suffered a psychotic fit and killed the couple’s nine-month-old child; the parents of her students then told him that they still believed in her and wanted her back at the school. Malmros’s film adaptation of these events unfolds from the perspective of his alter ego, filmmaker Johannes (Jakob Cedergren). Johannes learns of the tragedy early on, and the bulk of the ensuing film shows him considering what he might have done differently to help his wife Signe (Helle Fagralid), as well as himself. What keeps the couple together—past the points of mutual forgiveness and mutual understanding—is love. The film shows Johannes and Signe progressing from flashbacks into the present and towards the future, with the two people continuing to try to build a happy life.

The real-life couple is still married today, and Malmros made Sorrow and Joy with his wife’s blessing. Their gift of a film fit beautifully into this year’s larger IFFR trend of films considering the recent past. The festival turned its gaze upon itself with the sidebar program “Mysterious Objects—25 Years of Hubert Bals Fund,” dedicated to showcasing highlights from the history of IFFR’s famed fund supporting films from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Of the 1,026 films that the HBF has financially supported, IFFR programmer Bianca Taal selected fourteen for this year’s program, including masterful debut features such as the Argentine Martín Rejtman’s Rapado (1992) and the Palestinian Elia Suleiman’s Chronicle of a Disappearance (1996).

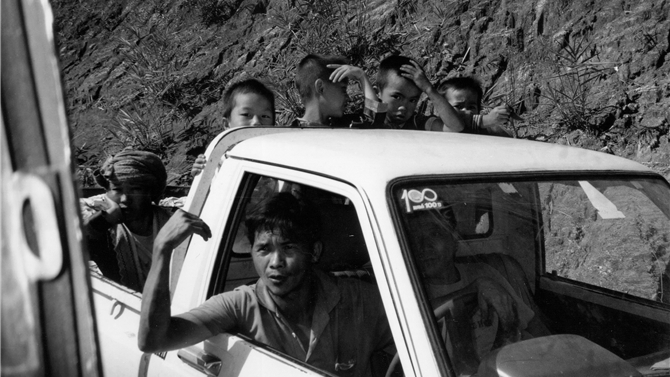

The program’s title pays homage to Mysterious Object at Noon (2000), the debut feature by Thai master Apichatpong Weerasethakul, which screened in a wonderful restored 35mm print courtesy of the Austrian Film Museum and the World Cinema Foundation. Apichatpong’s elusive black-and-white film takes place across the country, with people narrating pieces of a developing science-fiction tale about a teacher and her disabled pupil. The filmmaker himself sometimes appears on camera to coax his amateur actors into relating their parts of the story while leaving space for play.

“I remember that the Hubert Bals Fund committee was initially perplexed by my proposal,” Apichatpong writes by e-mail. “At the time I myself couldn’t imagine the movie because I had too many ideas. But after some resubmissions, the committee accepted, perhaps suspiciously. I actually think that if it hadn’t supported Mysterious Object, then I might not have finished the film. I felt an obligation to the Fund’s open-mindedness, and a big encouragement, of course.”

More information about the 43rd edition of the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR), which ran from January 22nd to February 2nd, can be found here. Thanks to IFFR programmers Edwin Carels, Evgeny Gusyatinskiy, Bianca Taal and Gerwin Tamsma for research help.

Aaron Cutler keeps a film criticism site, The Moviegoer, and works as a programming aide for the São Paulo International Film Festival.