Back in 2003, screenwriter Craig Phillips and Fandor co-founder Jonathan Marlow spoke with legendary filmmaker Pat O’Neill when he received the Persistence of Vision award from the San Francisco International Film Festival in a conversation largely centered around The Decay of Fiction. A decade later, Fandor is sponsoring two programs of Pat O’Neill’s remarkable work at the Ann Arbor Film Festival (where Marlow will be leading a discussion with O’Neill following the Saturday, March 23, screening of Water and Power). On the occasion of the latter screenings, we revisit this conversation.

Keyframe: In The Decay of Fiction (among other works), your use of optical printing and motion-controlled camerawork intentionally allows the seams of the process to be visible. That is a fairly distinct aesthetic choice.

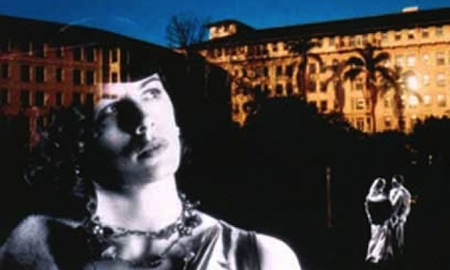

Pat O’Neill: In The Decay of Fiction, I was interested in how the camera moves in the space and then to make the seams both consistent and inconsistent with the background. So that the people seem to be in the rooms but they were not completely lifelike. I was interested in a kind of shorthand way of making a rendition. The idea was not to make a narrative film but to make a film that comments on the idea of narrative without really partaking in it.

Keyframe: Since you also work regularly on conventional feature films, how much does that experience influence or overlap with your personal films? Is there much of a connection at all?

O’Neill: There is some. I have worked on special effects for features and documentaries and I’ve done restoration work as a way of paying for the equipment to do my own work. I set up a company in 1973 that enabled me to hire some people and take in work and to make payments on equipment that was expensive at the time (and which is essentially junk today). We’re still using it and we still have a few people around who know how to repair it. But the commercial work and personal work are fairly separate from one another. One connection is that I tend to get stock material or ephemeral film footage. I am interested in restating things that were initially done many years ago but seem to have a somewhat different meaning when you recombine them today. This is the first film I have done where I’ve directed a cast and basically shot everything from scratch.

Keyframe: As The Decay of Fiction is making the rounds right now, are you and [cinematographer] George Lockwood in the midst of working on another project that also involves actors or was this an anomaly?

O’Neill: So far, we’re not doing anything else. It took all our resources to finish this film. And, unless I get some funding, I will probably be working on much more modest projects for a while. I am showing a couple of shorts with this feature [at the SFIFF screening] that are made directly to film, scratching on emulsion and hurling developer across the room at raw stock and then taking the result and working with it in a printer, taking rhythms that repeat. They’re very musical though they’re silent films. I have several other ongoing projects that involve landscape along with a documentary on people in the cities.

Keyframe: With the landscape projects, they are all filmed in Los Angeles?

O’Neill: I have been shooting all over the western states. Northern Arizona, New Mexico… It is quite inclusive.

Keyframe: What was the Labyrinth Project’s involvement in the production of Tracing the Decay of Fiction?

O’Neill: Labyrinth came into the project when I was part of the way through the shooting. I already had the background shot and was about to shoot the actors. We talked about the fact that we could make a database and use some of the shots that I’d made for the film but also a lot of other archival material that I couldn’t use. Storytelling by people who had some connection to the Ambassador Hotel or some documentation about the assassination of Robert Kennedy in 1968 and the botched investigation that followed that along with some talk about the neighborhood and how neighborhoods and populations change. The quality of life in a particular corner of a world changes radically from decade to decade.

Keyframe: Now that Decay of Fiction and Tracing the Decay of Fiction exist, is there an interest in making Water and Power and some of your shorter films out on disc?

O’Neill: I had not thought about it except that I’ll probably just end up doing it myself [and he has, quite some time later, via Lookout Mountain Studios].

Keyframe: You have mentioned elsewhere that there is one character who does not appear in the finished film, a homeless man you’d shot in your garage that contributed to a storyline told from his perspective. None of that seems to be included anywhere.

O’Neill: No, that has been eliminated. We’d tested it with him but I realized to put in a character that clearly defined would wind up taking over the gist of the film. I really wanted it to be more open ended than that. Instead, I made little sections that are distinctly different from the rest of the film. There is no background. They’re in a black void, more of a psychological portrait of someone who is more of a receptacle of my own fantasies and memories of being in places like that. The sort of the things you might think about on an idle evening in a hotel room.

Keyframe: Is there any pseudo-narrative connection to other films shot at the Ambassador Hotel?

O’Neill: Not really. Most of the films that were shot there (except for The Graduate) were made after it was already closed. In fact, there were a number of productions going on at the same time that we were shooting our scenes there. We had a relationship with the management, who let us come in and be in the hotel. Many of the shots took place through the night and day, taking ten to fifteen hours to complete. We spent a lot of time in the building. And then we went back and shot these actors in a big empty convention hall in the hotel against a black background.

Keyframe: What was it like to work with actors for the first time?

O’Neill: It was wonderful. It was also extremely stressful at the time because we had to direct actors operating in a void with no surroundings to anchor them. It became necessary to do everything with blocking and marks. But the actors were great. They would help with the dialogue and change things. They’d try to understand the story a bit more than they could. I’d say, ‘Well, if you understand it that way, that’s fine.’

Keyframe: The actors were looking for motivation from you?

O’Neill: [Laughs.] Right, they were building a backstory, and so on…

Keyframe: You mentioned that your expectation was that the building, the Ambassador, was going to be torn down and that would be incorporated into the film. It was clever that, without that footage, you included sounds of demolition over the end credits. Do you feel the film is finished the way that it is or would you want to go back when they demolish it [demolition of the hotel occurred in 2005 and was completed in 2006] and incorporate that footage?

O’Neill: I won’t change what I have now but I’ll go back if I can and shoot the demolition (which might wind up being a sequel or another short item that comes up after it).

Keyframe: The background footage that you shot is quite incredible. To then incorporate the ghostly figures of the actors into that space, you’ve described it as a much easier process than what is truly involved. Can you talk about the technical challenges you had to overcome?

O’Neill: The first thing that we found out is that it took twice as much light as we’d imagined to make the exposure bright enough on the actors to make them push through the background. We also had to change anyone’s dark wardrobe to something much lighter. We had some fifty lighting instruments for the shots that are quite large. Some of the biggest shots required people to move from about ninety feet away from the camera to about five feet away, so the amount of light that it takes to light a path like that was more than any of us imagined. We had to keep pouring on more and more light. That required us to have more power generators and so on. Just the mechanics of setting up the shot and laying it out and getting it lit and getting the light so that it doesn’t shine into the camera lens all took an incredible amount of time. I was continually urging everyone to be satisfied and get on with it because I could see I’d just be throwing hundred dollar bills into the furnace. I sort of became the producer in that regard, saying that it was good enough and to go with what we had. A lot of things that are a little on the rough side [are the result of my feeling that] it was important to get it done. Polishing beyond a certain point just got to be more than we could afford. But I think it’s all right that way. And people will get used to it. They’ll see artifacts of its making and that is part of it.

Keyframe: Seeing the rough edges definitely enhances the experience. In the complicated scene where they’re all in the room with the red walls, how many passes did you have to do in order to develop these layers of actors in that scene?

O’Neill: We shot three times with the same table and the same actors rearranged in different distances from the camera. We went through it once with the actors close and then again further back and then, once more, further back from that. We then wound up with three masters that we superimposed on the background. Figuring it out always took more time than we thought.

Keyframe: For your direct-animation pieces, scratching directly onto film stock, would you say that these films were influenced by the work of Stan Brakhage?

O’Neill: Stan is an influence on everybody working in experimental film. But I don’t think he was as much of an influence specifically on me as he was on some people. I would say Bruce Conner’s work has been a big influence on me, as has the work of Ed Kienholz, the installation artist, and a number of other static art makers. George Segal is another one.

Keyframe: What about Gerhard Richter?

O’Neill: I love his work. I don’t know if he is an influence, though. There are some animators over the years [who have been an influence] like Robert Breer whose work was very spontaneous and minimalistic. I’ve been making films for almost forty years and looking at a lot of work. They all become influences over time.

Keyframe: As an extension of that notion, what is it like working in experimental, non-narrative film in Los Angeles, the center of narrative cinema in the U.S.? How does your work fit in historically or conceptually given where you’ve been working?

O’Neill: I’ve always felt somewhat of an exile in Hollywood. The industry has absolutely no interest in experimental material. Although it is feeding into the production of trailers and commercials more than in features, it is kind of like working in exile in a way. I come to San Francisco or New York or even Paris and find people who are working along similar lines. I think the main reason I’ve stayed in Los Angeles all this time is that there is so much going on, technically, that the junk is better. You get more salvage opportunities (maybe more true ten years ago) in terms of raw stock and inexpensive lab work and people who can do anything. You can find that in San Francisco, too. But I’ve always had a kind of scavenger mentality towards the industry and what it makes. I’ve never had the ambition to become part of it. I don’t consider myself a storyteller. I’m more involved in the concept of the image-making than I am in joining that tradition. I don’t really feel that I have anything to add to it. It seems to me that people make a first film and then they wind up getting a contract to do another film and it often becomes a disaster because the things that the first film displayed were weeded out by the time the next project happened. I have always been aware of that being a pitfall.

Keyframe: That’s true of any commercial art, admittedly (particularly with music). How would you say your visibility has changed with the release of Decay?

O’Neill: It has changed. There’s a lot more recognition. A lot more people know about this place, the Ambassador, and have an awareness of it. The interest in the film has been quite strong, which is quite gratifying. I had no idea when I finished it how many people would want to see it.

Keyframe: Are you considering working with digital tools or do you remain interested primarily in working with film?

O’Neill: I am still working in film. I may do some of the operations digitally rather than on film but I am not sure yet. I have been doing another project over the last five years, making a series of still images ink-jet printed on paper. They’re not film-related at all. But the technology used to make them is sort of similar to what I’ve done in film except a hundred times more complicated and sophisticated. So far I haven’t gotten to the point where I can do that in motion. But I’m working on it (and making stills in the meantime).

Pat O’Neill films showing at the Ann Arbor Film Festival: Ojo Caliente (2012), Painter & Ball 4-14 (2011), Squirtgun/Stepprint (1998), Foregrounds (1979), Saugus Series (1974), Downwind (1973), Last of the Persimmons (1972) Fri/22, 9:30 p.m. Water and Power (1989), 7362 (1967) (Sat/23, 4:00 p.m.).