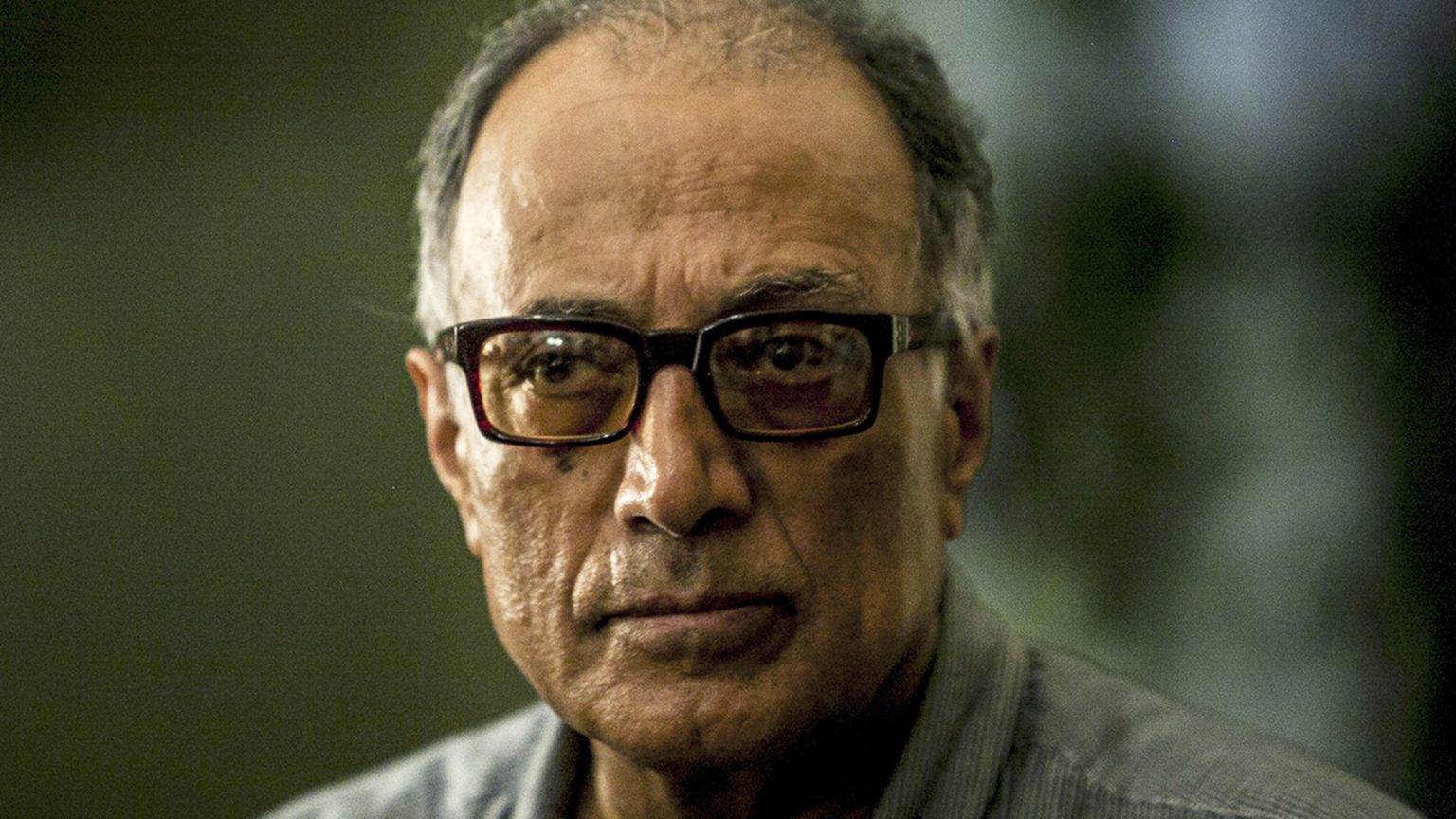

One of Iran’s foremost auteurs, Abbas Kiarostami’s cinematic legacy is one that’s undoubtedly etched into the history books. A Palme d’Or winning director, Kiarostami brought international attention to Iran’s film scene—including raising the profile of other filmmakers such as Jafar Panahi and Mohsen Makhmalbaf, among others.

There’s an understated quality to the films of Abbas Kiarostami. Featuring limited plots, but rich stories and characters. Kiarostami made films that are invested in images and the quiet moments of life. Using mainly static shots, his work might feel cold, detached, or distanced in comparison to much of the Western canon. Yet, in reality, Kiarostami was one of cinema’s most humane poets. In each of his films, he cast non-professional actors alongside more polished actors, allowing for small parts of the script to fall to the wayside in order to capture truth through amazing long takes. There’s a pronounced tenderness to all of his films.

In his slow-moving drama about a man driving around Tehran looking for someone to bury him after he commits suicide in Taste of Cherry, Abbas’ camera rarely strays from the confines of the car. The context of the world is narrow because this is a man focused on one thing: Killing himself. He can’t see beyond that singular goal. It’s not until later in the film, when he gets out of the car, that the beauty of the world is taken in—not only by him but by the audience. The camera is a guide into the psychology of the character, but it also operates as a metaphor for the experience of finding the world again after being closed off to it.

Even more experimentally, in Shirin, he filmed women watching a film adaption of a 12th-century Persian poem about a young princess courted by two men, a nobleman, and an artist. Kiarostami never shows us the film in question, but rather only the women’s reactions to the film. By doing this—and this is what makes Kiarostami such a special filmmaker—he didn’t just expect the audience to be an active participant in his films; he demanded it.

Eventually, Kiarostami would move out of Iran, working in Italy and Japan with internationally acclaimed actors like Juliette Binoche. And his work continued to grow in international stature until we lost him on July 4, 2016.

Nearly two years later, I still think about how each of his films impacted me. Yet of all of his films, it’s arguably his most polarizing, but award-winning, one that impacted me the most: Taste of Cherry. I remember watching Taste of Cherry for the first time. I was struggling with my first bout of overwhelming anxiety and depression. I had already seen Close-Up and Certified Copy prior to watching Taste of Cherry, so I knew what to expect with his films: The glacial pace, the unmoving camera, the quiet ruminations of what it means to love, to live, to die, and everything in between.

What I got with Taste of Cherry was so much more. Like the main character in the movie, I was going through an existential crisis, so choosing to watch someone else go through it, even in a film, might not, at first, seem like a great choice. But knowing the film was a Palme d’Or winner, I decided to watch it regardless. If, by the end of the movie, my own headspace was worse off than before, then so be it.

I watched the leisurely paced, mostly silent film in awe of how Kiarostami largely left his camera inside the roving car, focused essentially on one character, Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi). Badii drives around town, picking up strangers, asking them to bury him once he has committed suicide. Most of the strangers are understandably in shock, pleading with him to not go through with it and refusing to take part in what amounts to his own murder. Eventually, he does find a man who is willing to bury him. Yet, he also pleads with Badii. Not like the others, who were disgusted, but as someone who understands how hard life can be. The older man who sits in Badii’s passenger seat tells him how he once planned on committing suicide by hanging himself from a tree. He went out to a mulberry tree with a rope and attempted to do the deed multiple times, but had no success. He then decided to climb the tree and make sure the rope wouldn’t come undone on his next attempt. As he climbed the tree, he found ripe mulberries and decided to eat one. Then a second. And then a third—each sweeter and more delicious than the last. After indulging in these delicious treats, the sun began to rise and shine down on him, and the world around him became so much clearer and more beautiful than he had realized.

He leaves Badii with this story, saying that if he does decide to go through with his mission, he’ll go out to the designated spot and bury him the following morning.

Kiarostami never shows us what Badii decides to do, yet, as a viewer, one can assume that he, too, will find the beauty of life once more.

Watching the film, I can’t say I was cured of my anxiety and sadness, but I can say that I found the film’s poetic outlook on life exactly what I needed at that moment. Kiarostami’s films might not be for everyone, but for the willing, he proved to be one of cinema’s greatest humanists. A filmmaker is deeply interested in the lives of people. And that’s why on his birthday, we salute the masterful work he left behind.

Watch Now: Three films by Abbas Kiarostami — Shirin, 10 on Ten, Ten.