The legacy of Fritz Lang‘s 1927 epic Metropolis can’t be underestimated. The most ambitious and expensive film ever made by Germany’s Ufa Studio, it is a science-fiction landmark, a masterpiece of silent film, and a visionary work of cinema. Its influence on filmmaking and popular culture is immeasurable, its technical triumph is astounding, and the sheer scale of its production is still breathtaking. It was also a financial disaster for the studio.

Less than six months after its premiere in Berlin, Ufa cut Metropolis down by over thirty minutes for general release, and it was edited further for export (the American release was cut by more than a third). The edits were made to the film’s negative and to all circulating prints. For almost 70 years, audiences were left with an incomplete version of the original film.

The Murnau Institute embarked on a major restoration in the early 2000s using the film materials and archival records at their disposal and discovered just how much footage was missing. Entire subplots were lost when the film was edited down by Ufa and, even combing international film archives for alternate cuts, most of this footage appeared to be lost forever.

Fernando Martín Peña, a film historian, critic, and film collector in Argentina, believed otherwise. He spent twenty years tracking a fabled uncut print said to have been imported by an Argentinian film distributor before any of the studio-imposed cuts were made. In 2008, with the help of Paula Felix-Didier, director of Museo del Cine, he found his Holy Grail in the national film archive of Buenos Aires, Argentina. This damaged (and in places unwatchable) print, a 16mm reduction of an original 35mm print, had been locked away and forgotten for decades. It gave film restorers footage that had been unseen and thought lost since 1927, as well as a guide to Lang’s original editing scheme. This once-in-a-lifetime find became the foundation in the definitive restoration of Lang’s vision. Save for a few unrecoverable minutes of footage (the heads and tales of the well-worn reels were beyond salvaging), this was Lang’s full cut.

The footage from the Argentinean print — scratched and scuffed and washed out — stands out from the rest of the restoration, which comes from the best materials available and looks superb. Though physical and digital restoration can only do so much, these missing scenes fill out the full scope of the landmark film.

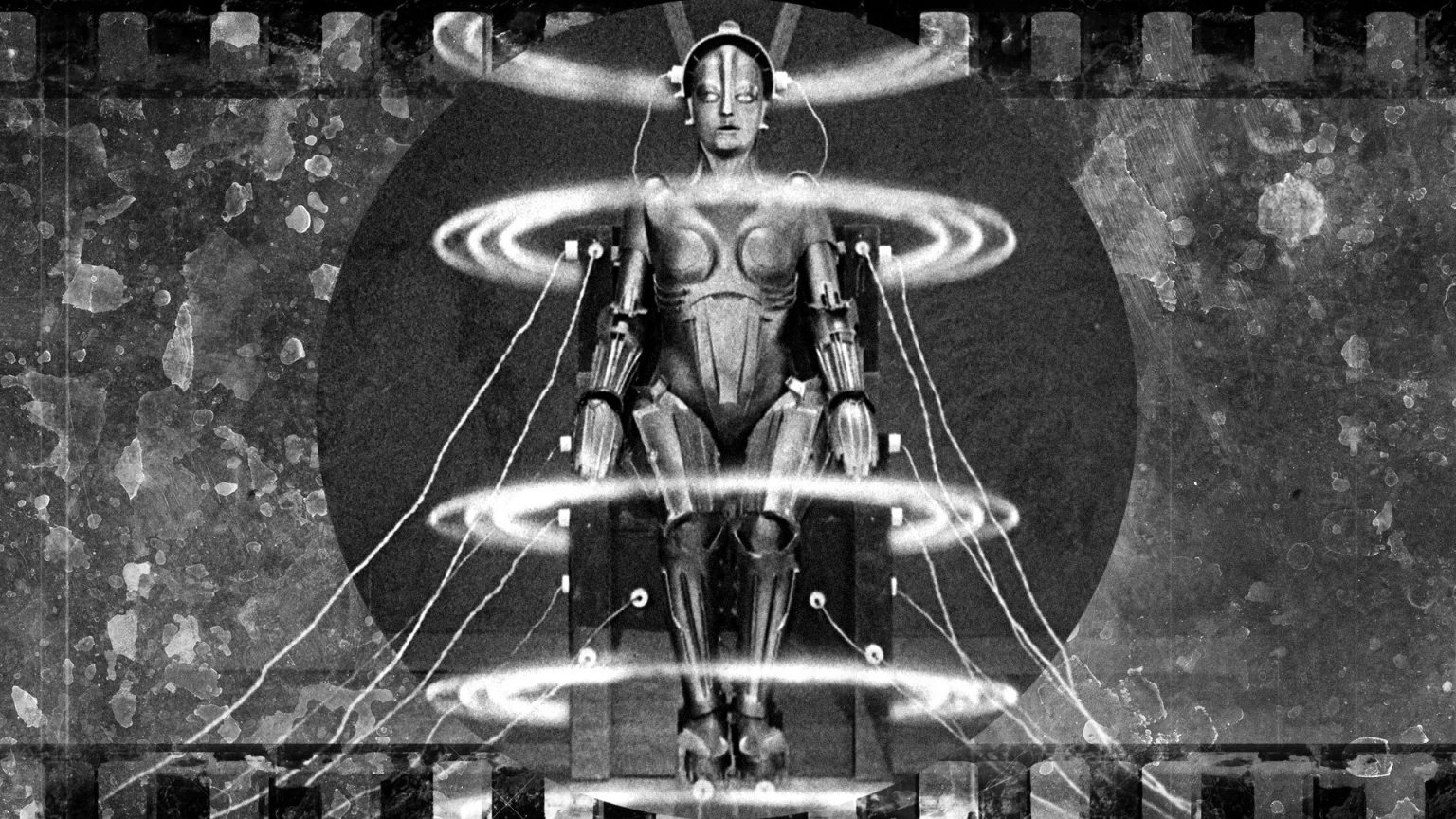

Lang’s Metropolis is a fantastical world very much like an ancient Roman society situated in an industrial future. The privileged class inhabits a glorious city of architectural marvels and aesthetic delights built by a virtual slave class of workers who are segregated into a sunless, joyless subterranean existence beneath the city. Visionary leader Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel) is an industrial mogul and authoritarian ruler determined to keep the lower classes in their place. His “golden boy” son, Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), is oblivious to the reality of his existence until he meets Maria (Brigitte Helm), a beautiful activist from the worker’s quarters. Her signature proclamation, “The mediator between head and hands must be the heart,” frames political science as a sermon, and her vague mix of class-conscious empowerment and religious prophecy preaches compassion and non-violence while awaiting the mediator — the messiah who will lead them from bondage — to arrive. Afraid of an uprising, Fredersen asks Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), his resident mad scientist of an inventor, to create a robot to impersonate Maria — a false messiah — and twist her sermons into a call to action so that he can justify violent repression. But Rotwang, twisted by his hatred of Fredersen, has his own kind of vengeance in mind.

The restored scenes give greater depth to this story through the journeys of characters discarded in the shorter cut: The Thin Man (Fritz Rasp), who in previous editions is sent by Joh Fredersen on a clandestine mission and then all but disappears; Joh Fredersen’s assistant Josaphat (Theodor Loos), who is fired by Fredersen and joins Freder in his odyssey; and the worker 11811, the man working the hands of the clock-like device, who journeys to the world above ground and becomes intoxicated by the decadence. The supporting characters and their experiences add to the richness of the narrative and provide character and personality to a film built on a saintly young hero and an impassive dictatorial antagonist. Gustav Fröhlich is a bit stiff as Freder, the starry-eyed idealist captivated by the Christ-like Maria (part labor leader and part religious prophet), and Alfred Abel is a stony Joh Fredersen, barely changing his expression throughout the film. The supporting characters and subplot trajectories leaven the spectacle and messages by offering more distinctive personalities who act and react individually within the otherwise faceless mobs. One could say they provide the heart that bridges the head and the hands (the big ideas and the visual spectacle) of Lang’s vision.

The restoration of the excised sequences and even brief individual shots also restores the rhythmic qualities of Lang’s editing and, in a few significant scenes, adds to the scope and intricacy of the drama. The visionary qualities become even more impressive in the full cut, allowing audiences to better appreciate the mastery of Lang’s use of scale and mass.

All of this adds up to a landmark of film restoration on par with Lawrence of Arabia and arguably the most exhaustive and extensive effort ever expended on a silent film. It is a true collaboration between the head, the hands, and the heart.

Watch Now: To see the film in all of its glory, check out Metropolis, streaming now on Fandor!