The first shot is of two feet shuffling forward. The camera pulls back until the feet stop and a boombox is placed onstage. Then it tilts up to reveal David Byrne: founder, guitarist, and lead singer of the Talking Heads. A cut takes us to the far back of the stage, empty but for Byrne, seen from behind with his minimal equipment. Next is another wide shot, but this time from the front—the crowd’s point of view—looking at the stage like a blank canvas. Byrne is duly credited with the conceptual design of Stop Making Sense and, more generally, the 1983 Talking Heads tour to promote their album, “Speaking in Tongues.” But what distinguishes this 1984 documentary as exceptional is the influence of director Jonathan Demme (The Silence of the Lambs, Philadelphia). Shooting over the course of three nights at Hollywood’s Pantages Theater, Demme may not have given direction to his performers, but one cannot discount his value as the guiding force behind the resulting film’s camera work, the breakneck tempo, and his influence on the thematic and literal idea of creative collaboration.

Following titles designed by Pablo Ferro (the man behind the similarly scribbled opening of 1964’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb), Stop Making Sense introduces Byrne as a solitary player. “Hi,” he says, before launching into the recorded beats of “Psycho Killer,” “I’ve got a tape I want to play.” Originally alone against a backdrop of ladders, scaffolding, and plywood, he is soon joined by bassist Tina Weymouth for the song “Heaven.” What starts as a somewhat awkward, peculiar acoustic solo becomes an intimate, two-shot rendition. Before long, as they perform (she’s not singing yet), a drum set is wheeled out and drummer Chris Frantz assumes his position for “Thank You for Sending Me an Angel.”

The camera scurries behind Frantz, less affected and more expressive than Byrne and Weymouth at this point, and the pace picks up. Keyboards are added, as well as bongos, guitars, and a briefly-glimpsed smorgasbord of supplementary instruments. And with these tools of the trade come the artists who play them, making their gradual way to the stage, song by song: guitarist Jerry Harrison, back-up singers Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt, keyboardist Bernie Worrell, percussionist Steve Scales, and guitarist Alex Weir. All together for “Burning Down the House,” the sixth track of the featured set, each individual provides an immeasurable dynamic—a distinct, enchanting voice, sound, and motion. Demme and editor Lisa Day construct a musical interface from this increasing mass of people and instruments. Through montage, dance, vocals, and visuals, a progressive rhythm emerges that makes it clear: Stop Making Sense isn’t your standard concert film.

This is just as well, for as Demme would contend, “This isn’t a concert film; it’s a performance film.” And this is partly why the audience is scarcely seen until the very end of the movie. Demme was tuned into the show as an ensemble exhibition, not necessarily a public event. To that end, Stop Making Sense transcends the conventional concert film (though this, by no means, is not the only reason why).

It certainly helps to be a fan of Talking Heads to enjoy Stop Making Sense, but at the same time, a dismissive “I don’t like the music” isn’t, necessarily, a relevant reason not to see it. There is something exceptionally engaging about this multifaceted showcase, something beyond the music itself, which, more than likely, will be infectiously enjoyed regardless of one’s musical tastes. “I thought the show had a funny kind of narrative feeling to me,” stated Demme, “one that I can’t describe—one that I don’t even care to try to describe—but I had a feeling I was seeing some kind of story, that I was meeting a group of characters as David attacked each new song.” There is, then, intriguing anticipation to Stop Making Sense, a suspenseful, curious wonderment in observing the spectacle of this “work-in-progress” production as each “story” of the performance is layered onto the previous one.

Center stage and often center frame, twisting in sinewy, gymnastic contortions, Byrne leads the kinetic charge, stopping only briefly for short breathers or incongruous comments—“Does anybody have any questions?”. Demme’s roomy framing encases an arena for the Talking Heads’ energetic stage presence. As if in a synchronized workout video, Byrne and company kick and twist, dance, stretch, and enthusiastically jog in place. Byrne dances with a prop light don a pair of glasses and gesticulates wildly. Most memorably, he appears in the appropriately dubbed “big suit,” an odd-ball guise inspired, according to Byrne, by traditional Japanese theater.

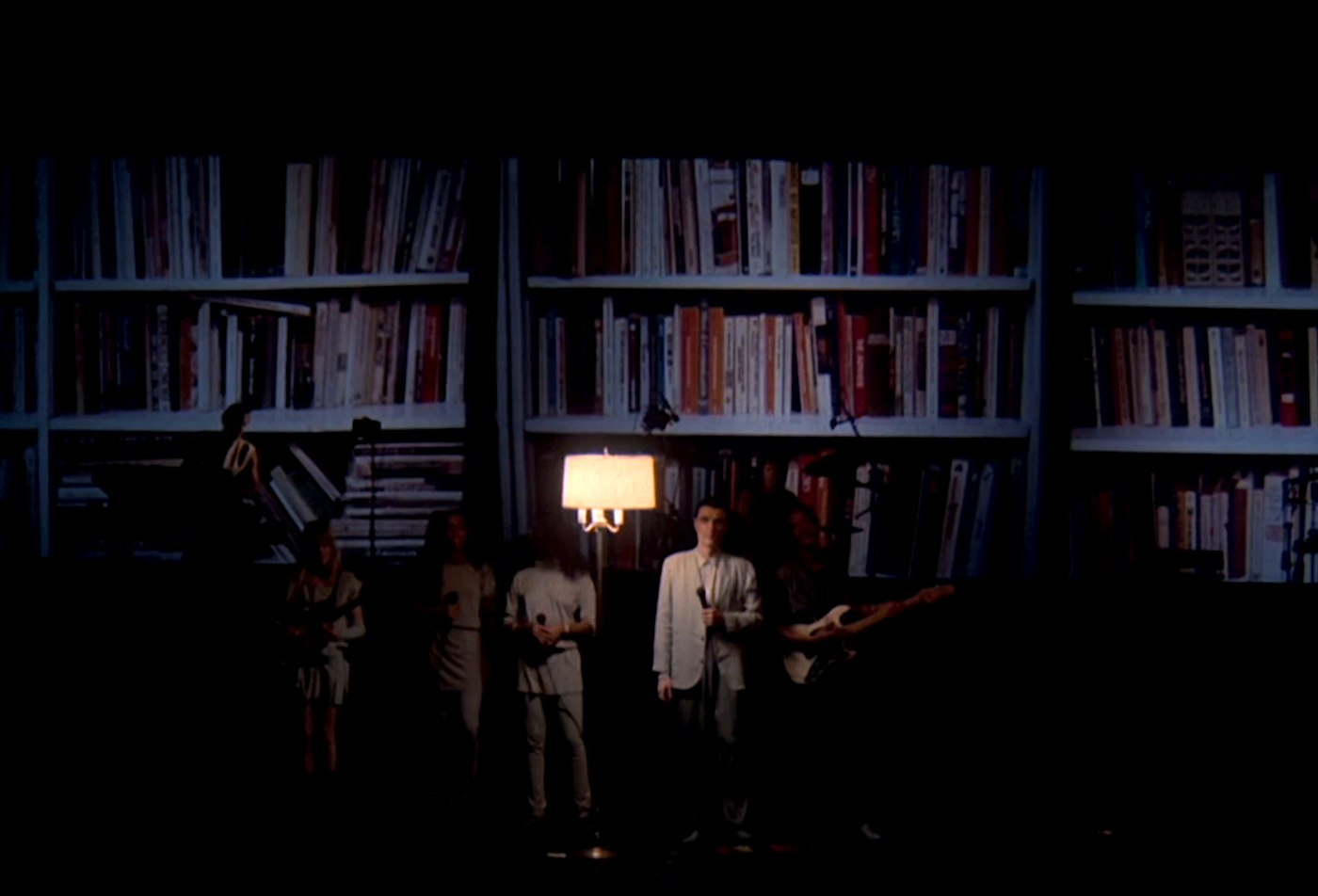

Like much else in the film, including the bland jumpsuits, sweatshirts, and sweatpants worn by the other performers, this oversized costume conforms to the picture’s palette of greys, whites, and pale blues. But while the color coordination may have started with Byrne, it is cinematically rendered by Demme, together with cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth.

Cronenweth’s eclectic credits include Robert Altman’s idiosyncratic Brewster McCloud (1970) and Ridley Scott’s visionary Blade Runner (1982)—Stop Making Sense is somewhere in between. Cronenweth worked closely with Byrne to outline the lighting cues, which, under Demme’s direction, give the film a low-tech artfulness that forgoes pyrotechnic gimmickry in favor of looming silhouettes, projected spotlights, a panoply of blue radiance, and colored square backdrops reading as a catch-all of 80s-era idioms.

Members of the Talking Heads knew Demme from his 1980 film, Melvin and Howard, but it was he who approached the group to collaborate after he realized the cinematic possibilities of their performances. Working on a $1.2 million budget (the majority of which was put up by the band members themselves) there is, during Stop Making Sense, an impression of going all out—and as it turned out this was the last Talking Heads tour. When the film was released, it clocked in at a compact 88 minutes. Given that the show typically ran for just over two hours, it’s understandable that a number of songs didn’t make the cut.

Directing and surveying the coverage and speaking with operators from a secluded video booth, Demme deployed eight cameras—efficiently and unobtrusively—to capture moments of startling action, like Byrne rising wide-eyed and uncanny for “Swamp,” an unexpectedly shifting tone, like from the boom, boom, boom of “What a Day That Was” to the joyous tranquility of “This Must Be the Place.” Minimal edits were also key. Demme preferred protracted close-ups and long takes.

According to Demme, “There is great power available by holding on to any extended terrific moment and letting the viewer become more deeply involved in the performance at hand, instead of constantly interrupting the flow with un-needed cuts. Too much cutting usually speaks to a lack of editorial confidence in the players and the music.”

Perhaps the most prominent hallmark of Demme’s direction in Stop Making Sense is the production’s collaborative nature. The film recognizes the charismatic band members as well as the unsung stagehands, and while Byrne may be the frontman, he naturally slips away for Weymouth and Frantz to perform “Genius of Love.” When Demme passed away on April 26, 2017, thirty-three years and two days after the film premiered at the San Francisco International Film Festival, Byrne shared a letter he wrote that noted this very quality: “Jonathan’s skill was to see the show almost as a theatrical ensemble piece, in which the characters and their quirks would be introduced to the audience, and you’d get to know the band as people, each with their distinct personalities. They became your friends, in a sense.” Like the best of Demme’s feature work, all of those involved in Stop Making Sense are afforded time to shine, generating an effusive portrait of a cohesive whole. As the end credits declare, after all, it’s “A film by Jonathan Demme and Talking Heads.” What a perfect combination.