[Editor’s note: Thom Andersen’s most recent completed feature-length film, The Thoughts That Once We Had, will receive its world premiere tomorrow (March 6) in Los Angeles at REDCAT.]

Early in Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003), an offscreen male narrator asserts that, “If we can appreciate documentaries for their dramatic qualities, perhaps we can appreciate fiction films for their documentary revelations.” He does so within the context of a movie devoted to finding truth in fiction. Los Angeles Plays Itself—a feature-length video essay crafted by Los Angeles-raised filmmaker Thom Andersen—offers a guided tour through the history of one of America’s most-photographed and myth-heavy cities, largely through clips from fiction films set in it.

Andersen presents scenes from nearly two hundred films, featuring Hollywood lows and highs (for instance, 1987’s Death Wish 4: The Takeover and 1944’s Double Indemnity) as well as experimental and independent records (including, though far from limited to, 1943’s Meshes of the Afternoon and 1977’s Killer of Sheep). He weds them to 16mm images (photographed by Deborah Stratman) of the then-present-day city, and ties all the registers together with first-person voiceover commentary, which fellow filmmaker Encke King speaks on his behalf. The sum of Los Angeles Plays Itself (whose title pays tribute to 1972’s “gay porn masterpiece” L.A. Plays Itself) is a complexly built argument about how films depicting Los Angeles have frequently tried to distort or annihilate much of it—including its economically struggling neighborhoods and their residents—and left the rare filmic efforts to reclaim the city’s true face to live under similar threat of erasure.

The film makes its points in ways that display sharp comic timing, surprising depth of observation, and humane sensitivity that does battle with frustration and despair. Its narrator observes at one point, in response to a rich and powerful villain’s seemingly inevitable property seizure at the end of Roman Polanski’s cynical Chinatown (1974), that, “This is history written by the winners, but as usual, it is written in crocodile tears.” Andersen’s search for those who have been potentially obscured by such history leads him towards a little-seen and largely extinct kind of American neorealist filmmaking represented by quiet communal studies like Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles (1961) and Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts (1984). These haunting, poetic, slice-of-life films depict “a cinema of walking,” in which disadvantaged people explore their surroundings and prove “that there once was a city here, before they tore it down and built a simulacrum.”

Los Angeles Plays Itself has been the subject of much acclaim ever since it premiered at the 2003 edition of the Toronto International Film Festival. It was only in 2014, though, that the film received its first commercial home video release. Many writers assumed that Andersen had trouble obtaining rights to film clips, but—as explained last year in an amusingly titled Los Angeles Times story—this was never the case. The fair use doctrine of U.S. copyright law allowed him to sample freely from other filmmakers’ work for illustrative and argumentative purposes. His film failed to land distribution in the decade following its premiere because no distributor made him a reasonable offer.

Last year the American company The Cinema Guild acquired distribution rights to Andersen’s first four feature-length films, all of which are documentaries and which include Los Angeles Plays Itself. In 2013 Andersen had completed a remastering of his film that involved replacing its original low-quality clips with material taken from DVD and Blu-ray sources, and the company released this new version of Los Angeles Plays Itself on home video and through online digital platforms last September. A similarly remastered version of Red Hollywood (1996) was released for commercial home viewing in December; Cinema Guild’s releases of a restored version of Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer (1975) and of Andersen’s recent Reconversão (2012) are planned for later this year.

Andersen (who was born in Illinois in 1943) has made his living primarily as a film studies instructor, most notably at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts for short), where he has taught since 1987. He is also the author of much brilliant film criticism published in outlets such as Cinema Scope, Film Comment and Sight & Sound. He holds an unusual place in American film history for the ways in which he has blended filmmaking, viewing, programming, critiquing and teaching. His films alone are the work of a many-layered self, with Andersen’s voice speaking through them variously as an essayist, archivist and activist.

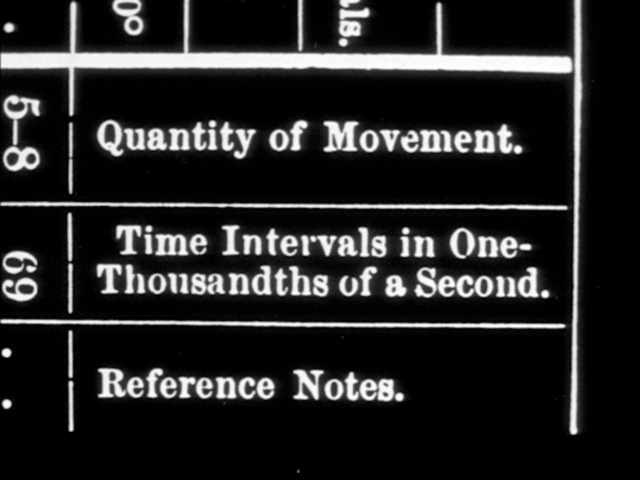

He made his first feature-length film, Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer, during his time in graduate school at UCLA. The film (narrated by Dean Stockwell) offers a lucid and accessible hour-long introduction to the work of a pioneer of modern photography: Eadweard Muybridge, a British man who spent much of his life in the United States, where in 1879 he invented a projection device called a zoopraxiscope to animate still images.

Andersen’s film presents several areas of Muybridge’s work, including the Englishman’s rich and then-relatively unknown 1860s photographic portraits of California landscapes. He demonstrates the zoopraxiscope’s effects by animating Muybridge’s sequenced still images of animals and human beings. In these moments, we see how Muybridge was radical for the subjects he often chose along with how he set them in motion: Nude people of both genders, in a variety of shapes and sizes and from a broad range of social classes, performing “actions incidental to everyday life” such as drinking tea, leaving bed, and emptying buckets. Their lives and routines are shown to be worthy of art.

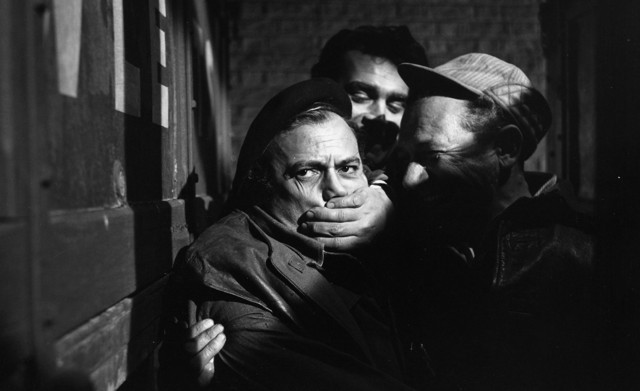

Two decades later, Andersen completed his second feature-length film, Red Hollywood. He made it in collaboration with film theorist and documentarian Noël Burch, with whom he also co-authored a related book published in French called Les Communistes de Hollywood: Autre chose que des martyrs (1995, a.k.a. The Communists of Hollywood: Something Other than Martyrs). The two men set out to rehabilitate the reputations of Hollywood film artists who were blacklisted during the McCarthy era and who, after essentially having ceased to work in films as a result, were unfairly labeled as talentless.

Red Hollywood aims to redeem their work mainly through highlighting scenes from their films, which include stunning works such as Force of Evil (1948) and Salt of the Earth (1954). The clips are accompanied by voiceover commentary (spoken by Billy Woodberry) and by talking-head interviews recorded with a few surviving formerly blacklisted directors and screenwriters. Red Hollywood unearths a motion picture industry far more willing to deal with American working-class struggles and social inequities prior to McCarthyism than it was afterwards. The film shows the “Communists of Hollywood” (whose ranks far outnumbered those that were blacklisted) to have also been outspoken feminists, civil rights activists, and labor reform advocates—in other words, social progressives. A present-day viewer might be startled by the directness with which these old films’ characters state a need to change their society, a need that Red Hollywood suggests still remains.

Andersen followed Red Hollywood with Los Angeles Plays Itself, which explores different territory while sharing several of its predecessor’s methods and beliefs about how the landscapes of American film and of American society have mirrored each other over time. His interests were reconfigured further in Reconversão, a documentary about the work of the celebrated Portuguese architect Eduardo Souto de Moura whose title translates to Reconversion. The film presents original footage of seventeen structures by the still-active Souto de Moura, who has designed residential homes, shopping centers, gardens, and many other kinds of architectural spaces. It takes special interest in Souto de Moura’s efforts to convert abandoned spaces for functional use while preserving their original designs.

Reconversão (whose voiceover text, a mixture of writings by Souto de Moura and by Andersen, is again spoken by Encke King) shows these buildings in a way that unites different construction processes. The edifices are offered through what Reconversão’s cinematographer Peter Bo Rappmund describes as “a proto-cinema technique,” in which myriad individually snapped digital still photographs are joined together into animated sequences of people, animals, and plants in rapid motion around the buildings at the time they were filmed. Rappmund compares this technique to Eadweard Muybridge’s connecting of still images to create the appearance of movement. Like projects carried out both by Muybridge and by Souto de Moura, Reconversão gives a sense of its own creation, including the lives of people who have been involved with that work.

Andersen’s short films include Olivia’s Place (1966), a veritable time capsule filmed during a single visit to a famed, now-defunct Santa Monica diner while it was still operating; Get Out of the Car (2010), a 16mm companion piece to Los Angeles Plays Itself that pairs images of Los Angeles billboards, signs, building façades, and sites of vanished cultural landmarks with a sampling of nearly sixty years’ worth of music recorded in the city; and The Tony Longo Trilogy (2014), a brief epic about a Hollywood bit player that treats viewers to three of the beefy Longo’s most action-packed film roles in their entirety, resulting in fourteen poignant minutes. His short Juke: Passages from the Films of Spencer Williams (2015)—based on the 1940s work of the African-American actor and filmmaker—will premiere at New York’s Museum of Modern Art this summer.

His films serve as a series of records of things he believes to be worth preserving. Andersen gives his rendering of the history of cinema itself in The Thoughts That Once We Had (2015), his most recent feature, whose world premiere will occur this Friday. Thoughts takes as its inspiration the philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s writings on cinema, to which Andersen adds years’ worth of personal observations on films that have mattered to him. Excerpts from films hailing from an array of eras and countries are woven together without voiceover commentary; though written text sometimes appears onscreen, the clips are left largely to speak for themselves.

Andersen spoke with me by telephone over a period of a few months last year, with the following edited interview emerging as a result. The Thoughts That Once We Had was far from finished at that time and never came up in conversation. Our focus was rather on films that he had completed—how and why he had made them, and what had happened to them and to their subjects over time.

Aaron Cutler: Is it correct that you were born in Chicago?

Thom Andersen: Yes. My parents and I moved around quite a bit, all in the Midwest, before we settled here.

Cutler: At what age did you move to Los Angeles?

Andersen: I could say three, but it was more likely four. It’s possible that my understanding that all films hold documentary value came from the fortune of living in Los Angeles and seeing the city depicted on film so often. I think that two films in particular were formative for me in this regard. The first was the original film version of The War of the Worlds (1953), which I saw upon its initial theatrical release. (After seeing Independence Day [1996], I thought it possible that most cinematic depictions of aliens could be traced back to that film.) The second was the Los Angeles-set noir film Kiss Me Deadly (1955), which I saw for the first time on television three or four years after it came out. Especially in the latter case, I was fascinated by the movie’s locations as much as I was by its story. Then, once I began seeing Direct Cinema films, I pretty much lost all interest in making fictional narratives.

When I started becoming a moviemaker, I was interested in capturing my perceptions of places in more immediate ways than I had seen in films. I always thought that the point of making movies was to make something that didn’t exist already. I began by trying to create things that previously hadn’t existed formally, but even while making my first movies, I also believed in the possibility of recording structures for the use of posterity—to extend particular times and locations so that they lasted longer through film.

With two of my early shorts, Olivia’s Place and — ——- (a.k.a. The Rock and Roll Film 1966-67, co-directed with Malcolm Brodwick)—both of which have recently been restored by the Academy Film Archive—I did something unconventional. I presented architectural shots of nightclubs, which other filmmakers probably hadn’t considered worthy of such an approach. This is especially true in the second film. In that film there was Pandora’s Box, whose closing led to protests along Sunset Strip. (They became known as “the riots,” but that’s not an accurate term.) There’s also a shot of The Trip, an important nightclub where The Velvet Underground first played in Los Angeles and where I remember seeing The Byrds and James Brown perform. We made a tracking shot along Central Avenue in South Los Angeles, where the city’s black nightclubs once were.

Those films contained a lot of esoteric meanings that I would make more explicit with the combinations of cityscape and pop music that I used in Get Out of the Car. My concern with depicting urban architectural spaces didn’t emerge for the first time during the 2000s, in other words. I was exploring it back in the middle of the 1960s. Studies of landscapes, cityscapes, and the relationships between the two have figured into all of my films.

Cutler: Were you thinking about backgrounds as you selected Red Hollywood’s clips of working-class characters walking on city streets?

Andersen: No, I don’t think that that was something that Noël and I had in mind. I think that it’s simply already in the films, and so it emerges in our selection. Of course it’s true that Red Hollywood contains many shots of people walking—from Marked Woman (1937), from Dust Be My Destiny (1939), from the beginning of The Asphalt Jungle (1950) with Sterling Hayden walking around Bunker Hill. (You can tell where he is, or at least I can, because of the Los Angeles Times building in the background.)

Some of these kinds of shots also come up in Los Angeles Plays Itself, one immediate example being the images of Native Americans wandering the city by night in The Exiles. There’s a lot of walking and not a lot of driving in these films I excerpt, and if you want, then you can read this distinction as a class marker.

Cutler: How about in Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer?

Andersen: In that film they’re there with my discussions of some of the ways in which Muybridge distinguished people from their different backgrounds, and with the film’s section devoted to his landscape photography, with which people generally weren’t familiar when my movie first came out. I first conceived the film in 1964, at a moment when there was a growing interest in Muybridge’s work. He was one of the first artists to use serial imagery, and one of the first to use a grid in photography. His time had come.

I made Eadweard Muybridge as my thesis film while I was a graduate student at UCLA, at a time when Ronald Reagan had only recently inaugurated tuition fees at the University of California and an MFA student could still stay in school indefinitely. It was the first of several overly ambitious thesis film projects that UCLA’s Department of Theater Arts allowed to be made during the 1970s and 1980s, a list that came to include Haile Gerima’s Harvest: 3,000 Years (1976) and Bush Mama (1979), Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977), Larry Clark’s Passing Through (1977), Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts, Nina Menkes’s Magdalena Viraga (1986) and Border Radio (1987), co-directed by Allison Anders, Dean Lent and Kurt Voss.

In a way, though, my film was the most ambitious because it was an animation film, made with traditional cell animation, where you could see each individual image in a Muybridge photographic sequence moving one by one. It was a difficult film to finish, and maybe the only film I’ve made on which I felt completely out of my depth. A lot of the credit for it belongs to my gifted collaborators, including Fay Andersen, Morgan Fisher and the composer Michael Cohen.

I completed the film with help from grants in December of 1974. It was released the following year, and it probably played everywhere that it could have played at that time. It did OK, but it certainly didn’t bring in enough income for me to support myself. I worked a number of jobs after graduation, including driving a taxicab, which wasn’t anywhere near as lucrative as it was made out to be at the time in Taxi Driver (1976).

I learned that the only job that I had actually trained for in graduate school was as a teacher of filmmaking. I tried to land such a job and first succeeded in doing so in the fall of 1976 at the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York (aka SUNY Buffalo), where my teaching colleagues included the filmmakers Tony Conrad, Paul Sharits, and Hollis Frampton.

Cutler: The film that you made following Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer was Red Hollywood. How did it come about?

Andersen: As a teenager in West Los Angeles, I was aware of the Hollywood Blacklist as being kind of an open secret. Dalton Trumbo received screenwriting credit on a few films such as Spartacus (1960) around that time, but the situation was really only acknowledged publicly when Ring Lardner, Jr.’s article ‘My Life on the Blacklist’ was published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1961. I had always held the Blacklist in the back of my mind and kept up with its literature, beginning with John Cogley’s book Report on Blacklisting (1956), which was critical of it. In those days I was interested in politics and even involved in movements to get rid of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, which was abolished sooner than we expected.

As I continued to follow the writing that was being published about the Blacklist, I noticed that people seemed to be very interested in the anti-Communist films that Hollywood produced in the late 1940s and early 1950s. I watched some of those films and shared that fascination, but to me they formed a kind of political camp, and were really of only limited interest. Partly as a result, I began to notice the lack of attention paid to films that were written and directed by blacklisted film artists. I would come across passing references to them at times, such as in Raymond Durgnat’s writing, but little more than that. Yet several of their films were quite strong, and the notion that their presence in the Hollywood film industry didn’t matter seemed counterintuitive to me.

I published my first essay about the Blacklist in 1985. The immediate spur to writing was my reading Victor S. Navasky’s Naming Names: The Social Costs of McCarthyism (1980), which I believe was the most successful of all the books on the Blacklist. Certainly it was the best-reviewed. I thought that the book was vicious towards the informers in the same way that other writers had previously been vicious towards those who didn’t inform. It’s obtuse to blame the Blacklist on the informers, as Navasky essentially did, because in placing blame on them one turns attention away from the much more powerful entities thatdeserve to be excoriated: The owners of the Hollywood studios. The Motion Picture Association of America. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The Hollywood labor unions. So that’s what led to the article.

The idea for collaborating with Noël Burch on a film about the Blacklist emerged when he and I were colleagues in the Department of Photography and Cinema at Ohio State University for a couple of years in the early 1980s. Noël’s job marked his return to the United States after much time spent living in France, and he attributes a clearer understanding of the political significance of films to his time here.

Noël was a great teacher and a great colleague, but during that time a conflict emerged within the department that led to the denial of tenure to me, to Allan Sekula, and to a photographer named Jim Friedman, which is to say that everyone without tenure didn’t get it. It was clearly a purge. One of our enemies said, ‘We have to get rid of the Communists and Jews,’ or ‘the cosmopolitans,’ to use the old Soviet term. Unfortunately for him, he said it to the wrong person and the cat got out of the bag. The university Provost accepted the Department’s decision, but because its faculty had bungled the situation so badly, he actually broke up the Department itself.

I spent the next two years unemployed until joining Allan at CalArts, where I still teach in the School of Film/Video. Noël and I had discussions during that period about the work that I was doing on the Blacklist. We decided early on that we would make a film about it. I don’t recall if that was his idea or mine. We spent a year doing research together when Noël was teaching at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and then we shot an interview with Ring Lardner, Jr. a few years later at the Amiens International Film Festival in northern France.

For me, Noël’s big contribution to the film and to our other work was his belief that you always had to start from scratch. You couldn’t accept any received opinions. So what that meant was that we set out to see every film that might be relevant to us, which is to say every film involving a blacklisted writer or director that, judging from the summaries we had available, might contain some political content. We saw hundreds and hundreds of films together on a combination of video copies and film prints without being able to raise enough money to make the film, until I came to believe in the mid-1990s that realizing a cheap, sketchy video version of what we had wanted to achieve would make the most sense.

Noël returned in the summer of 1995, and we threw out the script from which we had previously been working and composed the whole film anew. Red Hollywood had a long period of research behind it, but the film’s production essentially occurred during those three months.

Cutler: How did Billy Woodberry come to speak Red Hollywood’s voiceover commentary?

Andersen: Billy has a nice voice and a nice way of talking, which was important, as it was with Dean Stockwell for Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer and with Encke King for Los Angeles Plays Itself and Reconversão. Availability was also fundamental in all those cases, as these people have been in my immediate vicinity. (Billy was teaching at CalArts at that time.) The third major element has been legibility. I need my films’ narrators to be able to speak the text in a way that will be heard and understood, and so that it won’t be forgotten.

The fact that I ended Los Angeles Plays Itself with clips from Billy’s film Bless Their Little Hearts as an example of a vanished kind of American independent cinema was a coincidence. I knew about and valued American neorealist filmmaking at that time, but I didn’t have my later film in mind when we were making Red Hollywood.

Cutler: Was Los Angeles Plays Itself based on any teaching lectures that you had given?

Andersen: No, I essentially created the film in my head from scratch. I simply wrote and imagined images in my head to go along with what I was writing, or imagined words that could be spoken with the images.

It is true that when VHS tapes first appeared, I became an advocate of their usage, since they gave valuable access to material that could demonstrate points about film composition (something that has also proved true with other home video formats). I found them to be useful teaching tools, and you could say that that method of teaching looked forward to some of my films.

I will also say that I showed and discussed L.A. Confidential (1997) in one of my ‘Film Today’ classes when it came out, and that I believe that what I said about it then was similar to what the voiceover would say in Los Angeles Plays Itself: ‘Cynicism has become the dominant myth of our time, and L.A. Confidential preaches it. Cynicism tells us we are ignorant and powerless, and L.A. Confidential proves it.’

Cutler: Why restore and remaster your films now?

Andersen: Ross Lipman, a film preservationist at the UCLA Film & Television Archive, had been interested in restoring Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer for a long time. All the 16mm prints of the film had worn out to the point of being unprojectable, and the internegative had gotten lost at the lab, so new prints were impossible to make. Ross was finally able to get the funding this past year for the restoration, which ended up being more like a recreation. First, the film was blown up from 16mm to 35mm. Additionally, it had originally been shot in black-and-white with the assumption that Muybridge’s photographs could be correctly color-toned during the printing stage; the UCLA restoration team made it possible for us to finally get this right and make something closer to the way that Muybridge’s original photographs and photogravures looked.

I had previously mentioned that my early short films have also recently been restored. In making new prints of them, the Academy Film Archive made optical negatives for the first time. (Originally the films’ soundtracks were electroplated.) These restorations cost more than the films cost to make in the first place. I lacked the resources in the 1960s and 1970s to make my films how I would have liked to make them, so the restorations and recreations made it possible for me to achieve my original intentions.

I personally funded the remasterings of Red Hollywood and of Los Angeles Plays Itself (which were inexpensive). Those films were originally produced on Beta SP, which is now an obsolete format, with older film clips copied from VHS tapes. I was able to remaster them in a combination of HD and SD from Blu-rays and DVDs to improve the quality of the images. I also did some reediting to change things about the films that had bothered me when I watched them projected. In neither case was there any effort to update the work, and in both cases the narration was left the same as it had been in the original theatrical cut.

Noël was not involved in the Red Hollywood reediting. He is constantly rethinking his positions and reorienting his central project, and he’s much more interested in moving forward than in going back to the past. He basically said to me that I could do whatever I wanted. I made some additions to the film, such as a short scene from Mission to Moscow