According to Christopher Lee, Bela Lugosi’s fan mail was full of letters from women with a “strange attraction” to Dracula. Surely, it’s something to do with his eyes. The doc In Search of Dracula portrays Todd Browning’s 1931 horror, Dracula, as the cultural product that brought the vampire out of its shadowy subgenre and into full genre “light.” Since then the lore of the vampire has been so rampantly retold, regurgitated and lampooned it’s just about impossible to remember where the whole thing started. Could vampires have a Garden of Eden (Garden of Evil)? I love the idea, but lore is perpetually regenerating, so finding an origin point, whether literary (Dracula, Carmilla, The Bride of Corinth) or historic (Prince Vlad the Impaler, Countess Elizabeth Bathory, Lord Byron) becomes a frivolous exercise. Plus, it’s not as fun as watching the obsessive patterns this horrifying and romantic genre parades about. Who doesn’t love? Who doesn’t hurt from it? Who hasn’t felt like someone was sucking the life from him? Who already feels like their life is a gothic opera? The barely housebroken, that’s who; i. (Sildenafil Citrate) e., tweens.

Browning’s Dracula may have been mainstream but it’s the size of a small town parish compared to the megachurch that is The Twilight Saga. And if you think the sublimated desire and gory diet of the undead was broadly portrayed in the grown-up Dracula, tween Dracula is even broader. With only some exceptions, the desire is not just sublimated, it’s renamed; adolescence ends with actual physical transformation (instead of bloodletting: blood sucking); and the alfresco dining happens mostly out of frame. The soap in this opera has bleached the graphic bits out, allowing the love story to retain the ardor, the terrifying emotion and the ferocious need of the vampire drama, while still being true to the intensity of teen desire. Arguable, Kenneth Lonnergan’s Margaret was about the same teenage relationship to feeling and performance but the catharsis was for an audience who could deconstruct the feeling without the help of fantasy. Still, if Anna Paquin’s fusty, privileged character in Margaret isn’t the real-world’s vampire equivalent, I’m not sure who is.

As the upper-class demon in the universe of Victorian monsters, the vampire is the most sanitary. He has sacred few bodily fluids, looks down on the unwashed and won’t even consider destroying them lest he dirty his manicure. Am I making him sound fey? (I’m trying.) But in addition to being dismissive of the efforts required by the peasant or the woodsman, he was also meant to be a gentleman, and a man of the leisure, bound by convention and propriety: He holds the door for the lady, demonstrates the respectful principles of social congress, knows how to lead on the dance floor. It’s the romantic ideal because it’s respectful and his decorum obscures the beast he becomes behind closed doors or curtains. Edward (age 100+) matches the ideal and happens to have been alive and biting during the Victorian era. Are smart teens everywhere to conclude gentlemen are as prevalent (or as imaginary) as vampires? Best of luck finding that boyfriend.

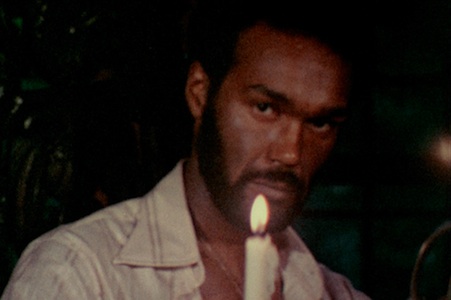

It might seem that the Wolfman is the better alternative, but siding with the werewolf is as defeatist as siding with a zombie: all paths end the same place. However, the werewolf is a less malleable myth, which is likely why he’s not as heavily repurposed. He’s physical and woodsy, he ravages everything, he’s a loner unless his pack mentality actually connects him to a family, and how often does that happen? (Jacob has a family. And he’s the Alpha. Just saying.) So naturally vampires get more action. Their stories are easier to twist around: vampires can reveal paradoxes, powerlessness, alienation, pathology/deviance. The list is long. Writer Director Bill Gunn used vampires as a metaphor for blackness in Ganja and Hess. Star Duane Jones (Night of the Living Dead) doesn’t have to lure women with his eyes, voice or mojo, he has good, old fashioned, swagger. The chemistry’s so hot you’ll scream like you did when Renesmee died. JUST KIDDING!

Dr. Hess is the “only colored on the block;” a doctor in an expansive estate with a crass and anxious houseguest (played by the writer/director) whose issues with his bloodthirst get the better of him. After his guest kills himself, the guest’s wife Ganja comes a-knocking. Ganja is gorgeous but just as moneyed and lowbrow as her hubby was, making an awkward fit for the elegant and commanding Hess. He falls for her anyway. He makes her immortal. They have to kill to eat (they’re basically particular about eating minorities) and the sucking ritual is unilaterally attached to other sucking rituals, if you get my meaning. But what Ganja and Hess express is that they’re victims and murders simultaneously: they’re guilty of their desire and guilty of their crimes, their imprisonment in eternity is their cross and their crime at once. This makes it easy to see how vampirism is like being any kind of “other” and blaming yourself for feeling “different” when you could be feeling “special.” These people aren’t constrained by their color the way they once were but all that precious constraint doesn’t spontaneously evaporate—healing isn’t instantaneous.

Consider the contrast to Edward Cullen’s alluring otherness: he’s not weird, though he might be misunderstood, but all that suggests he’s insightful and sensitive. Hess’s otherness is part of his lot as a black man, but there’s more to the otherness than can be witnessed, which transforms Ganja and Hess from blaxsploitation to philosophical inquiry by surprisingly elegant means. As true to black cultural tropes as to vampiric ones, Christ saves the day. Amazingly seamless, don’t you think?

Within the first moments of Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn 2 the campy sound effects become laughable. Bella goes “whoosh” when she runs. She bites prey like someone’s gnawing celery. I had flashbacks to the low-rent, Canadian exploitation video Jesus Christ: Vampire Hunter. Christ comes out to stop a team of vampires ridding Ontario of its lesbian population because they think the lesbians are low and “won’t be missed.” Jesus and the luchador Santos beg to differ. What convenient activism!

It’s true there’s a sub-genre of lesbian vampire movies (The Hunger, Vampiros Lesbos, etc.) but the naughty oral suggestion that connects vampires and lesbians isn’t in the equation here: The lesbian vampires don’t attract lesbians, they karate chop them. It’s somewhere between speed dating and screwing for sport.

When I went looking for vampire movies, the most literal connection I could make to Twilight was the Hong Kong horror comedy Dating a Vampire. I’m sure you see the association—sadly it’s as shallow as it sounds. Like Twilight, most everyone’s a student. Unlike Twilight, the masturbation jokes are explicit. Comparisons: exhausted.

Accidentally exhumed, three vampires hunt for “snacks” in an apartment complex inhabited by med students. When the mop buckets of blood start spilling, the students seek the services of a charlatan TV psychic, who’s more interested in fame than the supernatural beings literally assaulting him where he stands. The quality is reminiscent of Henry Jaglom but with more crass sizzle. Also, “dating” is a strong word…they just kind of like each other and know they’re star-crossed. It’s Bella and Edward from the first Twilight movie but with even less touching.

I don’t know if you’ve noticed but The Cullens live in a massive house. Theoretically the ability to stay awake forever should result in success in international business (no time zones). That said sleepless vampires have bountiful room to make money—unless their principles demand otherwise.

The Cuban animation Vampires in Havana shows how a trumpet-playing vampire is fed a vitamin cocktail that makes him impervious to sunlight and he uses his superpower to hide behind bedroom curtains in light or dark. This film’s equivalent to Twilight’s Voltori wants to mass produce and market the sun-shielding concoction and make millions, but the creator wants the cure to be free for all. Vampires are usually pretty class conscious (Dracula is a count…) which makes the charm of class bound monsters in socialized Cuba like a comic point proven: If vampires can share, who can’t?

Even the Cuban vampires were ladies men…oh how they loved the ladies…and it seems like most of the time vampires are an excuse to figure out mysterious veins of desire.

Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural is a 1973 exploitation that grossLy merges the promiscuous eroticism of the vampire with the development of a pristine teen. Lemora is a “singing angel” at the church run by adopted father, The Reverend (writer/director Richard Blackburn). When she learns her biological father is dying she steals away to care for him like a dutiful daughter, but when she sees he’s held hostage by vampires, her moral duties get confused with her mortal ones, because running from the vampires also means running from her sickly father and his “protectors.” What’s great about Lemora is also what’s disturbing about it: The world of this rare, pure girl is lousy with people who want to defile her. She can’t go anywhere and not be in danger of leering men and women, all intimating rape or molestation. Yes, she’s pretty, but instead of being an angel worth protecting, she’s almost “fair game.” In the face of that kind of victimhood, vampirism—which is a uniquely feminine and maternal thing in Lemora—looks kinda good. The world must be pretty horrifying and hazardous for vampirism to look like the best gig on the sexual horizon.

It’s intriguing that the Victorians seemed to think the sexual horizon was somewhat narrow—and even still found room in it to add a few weirdly literal monsters. While, medicine was having a disgusting time becoming “modern,” forensic psychologist and physician Richard v. Krafft-Ebing was compiling a list of the ways we do sex wrong. A century later, Bret Wood would make a low rent feature about it and name it after the text Freud would make obsolete: Psychopathia Sexualis. While Krafft-Ebbing had a particular interest in same-sex attraction he was also dead set that people out there were getting off sucking blood. It’s really a shame the whole thing is socially vile, because the guy who starts a strangely consensual relationship with his clumsy, window-cleaning maid seriously improves in health after he starts finger sucking.

So, if feeding is erotic and the Cullens eat animals, doesn’t that suggest something?

A mummy narrates Bizarre, a late sixties exploitation that takes the “battle” of the sexes literally. Sometimes the violence is erotic, but the underlying rationale for all aggression is revenge for the stress caused by the opposite sex. Women exploit their power and men exploit the women until they’re so mad they need guns. It’s Krafft-Ebbing after arms proliferation. In one sequence, a female photographer puts a model in shackles for a picture book on medieval torture devices. She coaches him at length about how traumatized he should look and how he’s sensitive and so should appear especially fraught. Then she puts him on a machine and goes for a long lunch while his man parts ooze. When she returns, his “uniquely” soiled white pants delight her like arty porn. More than any of the vampires I observed before Twilight, this one made me want a shower. And Lee Pace plays a vampire in Breaking Dawn 2—a smarmy one who eats street musicians.

Among all this conflation of eros and eating, the most disturbing vampire saga is also the most clinical. In Thirst, a well-to-do businesswoman is sequestered in a “dairy,” at which people are being bled to feed the ultra elite. (It’s OK, they pasteurize.) She’s a descendant of Elizabeth Bathory and the Dairy leaders feel it their responsibility to let her in on the drinking she’s been missing, so they indoctrinate her in the cultiest of ways, and after hallucinations, drugs and disorientation tactics, the story culminates in a perverse, late-life coming-out party. Jubilantly the head brainwasher says: “Drinking blood is the greatest expression of aristocracy!” There’s no sex in the vampire world; they’re above it. Feeding involves milk cartons and glasses. Bleeding happens into IVs in hygienic white stalls. Absolutely everything naughty is missing. The “I’d sink my teeth into that” jokes that permeated films like The Playgirls and the Vampire are impossibly nostalgic in this future. It’s like A Clockwork Orange but with less rape and more shining white surfaces. No desire is sublimated, but the parasitic authority of the upper classes is clear—why were we sublimating our desires before? I mean, they say once you’ve had O positive, you can’t drink anything else.

If we look at Twilight as a sort of soap-opera template of vampire lore, the gauziest elements are the most pronounced. The atmosphere is graced with cloud cover, the touching is furtive and the yearning is so intense that drama of the highest order is the only kind to explain the ferociousness of these feelings. What’s happening can’t be commonplace, it must be superhuman, but it’s certainly not “good” in any moral way. The dance of conflicting tensions is part of what we connect to, and if anything more spiritually conveys the little girl wonder and turbulent urges of Twilight, it’s Guy Maddin’s Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary.

When visitors from the east ominously enter the story, their routes appear on a map as blood trickling dangerously close to home, adulterating the white of the page like bridal linens on wedding night. Inspired by The Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s reprisal of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, this incarnation is the most ethereal and oddly pure expression of adolescence and magic anyone has put on screen and in a pair of fangs. The vampire is Asian, and his prowess overwhelms the expanses of swooning and eligible young ladies. Like Sessue Hayakawa in The Cheat, this Dracula is not just a gentleman, he’s a man with all the enigmatic conflict that suggests. He’s the sexual hunter, clearly identifying his intent; all morals are dwarfed by his resolute goal. The odd integrity of the monster proves his high breeding—even if he trades silk sheets for pine boxes full of dirt. He does what Mina’s fiancé can’t—he’s the aggressor, unafraid, determined. His hunger demands your submission; it’s a force like weather.

At the end of Twilight Breaking Dawn, Bella became a mother and then a vampire. To think: She resisted for so long. The next Dawn (Part 2), she graduates to Tiger Mom. All that wimpiness people complained about in previous films is gone, and she’s a mighty huntress, seemingly independent of any species for food. She doesn’t lure, she fells prey with sheer speed/force. She’s at the top of the food chain. ANY food chain. In her submission to the condition of aristocrat/parasite/abomination, she is exaltation. Otherness is small in the face of her wholeness. The goal is attained, purity was protected and the circle closed. It was hammy and hyperbolic, but when isn’t hyperbole a race car to your heart? Amping up melodrama is like turning up the radio—you can’t miss the moment; you’re soaking in it. Might as well give in.