One of American independent cinema’s secret weapons, Mark Rappaport is most famous for his AIDS-era postmod wedge of movie-movie rumination, Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (1992), but actually he’s been toiling on the fringes since the post-New Wave days, and is by now looking at the business end of a forty-year career. (His first feature, Casual Relations, was released the same year as John Cassavetes’s A Woman Under the Influence.) Rappaport’s films are neither entirely avant-garde nor dramatic narratives in a traditional sense; generally, you could say they’re post-“art film” launches of studied unease, so Godardian in their autocritique that they feel frozen in the headlights of their own doubt and questioning. Time doesn’t seem to move forward in Rappaport’s films; the literal atomization and neutralization of time in his Hudson film is made figurative in his fiction films. His third feature, Local Color (1977), is prototypical—an arch, stylized chamber piece in which eight relentlessly self-analyzing “characters” break up, make up, rationalize, swap and link up, the film plays out outside of narrative progression, as if like its inhabitants the film itself is stuck in a Zeno’s paradox of relationship conundrums.

Hitting festivals in the early months of the Carter Administration, Rappaport’s movie came at a time before “independent film” was a thing—punk hadn’t yet permeated the medium, and the initial manifestation of the Sundance Film Festival was still a year off. Jim Jarmusch was still in grad school. At the same time, 1977 was an ice-breaking year—American film culture didn’t quite know what to do with Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, David Lynch’s Eraserhead, Martin Brest’s Hot Tomorrows, John Waters’s Desperate Living, and even Cassavetes’s Opening Night, but clearly the anti-mainstream reflexes, lingering from the global New Waves of the sixties and perhaps responding to the Lucas-Spielberg homogenization of Hollywood film, were being felt. Naturally, Rappaport’s droll, hyper-ironic rondeau was under the radar, and did not find a sufficiently nervy distributor.

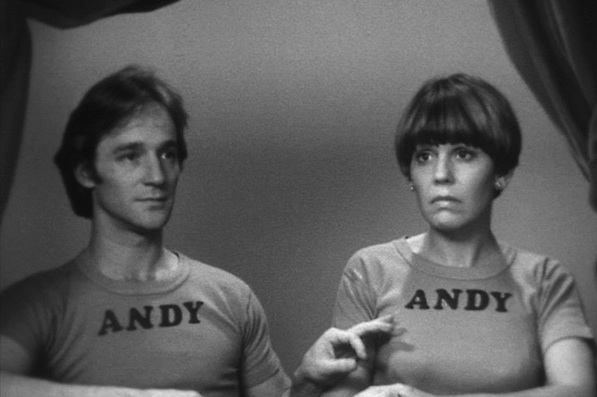

Grittily black-and-white, Local Color is also something of a Rorschach blot—depending on where you stand, you can see it as soap opera camp (as Vincent Canby did in 1977, dismissing it in a survey of the New Directors/New Films series), semi-Surrealist dream film, melodrama parody, threadbare feminist/gay research into interpersonal oppression, or experimental interrogation of cinematic-dramatic conventions. (Which is what the Hudson film is, among other things.) Or any mix thereof. Similarly, you can see the residual influence, intentional or not, of Douglas Sirk, Edgar G. Ulmer, Michelangelo Antonioni, the Kuchar brothers (an interface Canby surprisingly noted), and Samuel Beckett. The eight personae moping and backbiting through the film include a pair of eventually incestuous twins, a geologist, a dentist and his discontented wife; everyone seems to be whimsically bisexual (including the male-female twins), and no one can communicate properly or effectively, a struggle that consumes the film. (One couple goes to an “obscure Polish” opera; narrating, she claims it’s impenetrable, while he shrugs about its simplicity.) Gestures and behavior aren’t “real” so much as theatrically iconic—no one eats a meal but rather “eats a meal,” and film theory ideas of symbology and totemic resonance seem to define the movie’s form. Think of it, perhaps, as a film that takes place entirely in the mysterious meta-house from Celine and Julie Go Boating, but only in its grayer, plainer rooms —but still, the artificial and incantatory air of the piece was by 1977 a well-established, self-conscious style of the new global cinema, employed by Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Nagisa Oshima, Dusan Makavejev, Hans-Jurgen Syberberg, and Werner Schroeter. It became in the eighties a fashionable punk/”no wave” manner, evolving into Jarmusch’s ultra-laconic deadpan.

A movie that reflects in every frame on what a film image “means,” Local Color wears its postmodernism on its sleeve; as if following a semiotic manual on film noir, the characters keep discovering the same revolver in different places, using “Chekhov’s gun” principle as a running gag, and yet insistently suggesting that sooner or later Local Color, by way of gunfire, will eventually coalesce into an “normal” plot-driven, escapist melodrama, instead of the analytical exercise in personal politics it defiantly remains. The cast—most of whom would go on to appear in other Rappaport films—are all frostily posed and mannered, subject to the film’s dreamy style, and tied to Rappaport’s multi-perspective narration, with which the characters ceaselessly, and rather abstractly, question their motives, their loyalties and their attitudes.

Nothing is concluded, of course. Deliberately slippery about perceptions and presumptions—how much do we actually know about our loved ones, anyway?—Rappaport’s film is by now a bit of cinema history, an expressive window into a small moment in American film, when the underground began creeping into theaters on shaky New Wave legs, at the same moment that “blockbuster” became a genre and not a box-office demarcation. Halfway along the aesthetic timelines between Rivette and Peter Greenaway, between Kuchar and Guy Maddin, Local Color may be about Movies and Moviewatching on most levels, but it is also in the end an almost clinical study of modern unhappiness, and how we cannot save each other from ourselves.

[Note: The filmmaker notes that the print of Local Color made available here comes from a newly-restored negative made under the supervision of George Eastman House.]