As long as Hollywood has held sway over the movie industry, film producers have attempted to turn youth subcultures and movements into easily consumed silver screen fare. This is, after all, how we ended up with two movies about the Lambada. That should be example enough that those studio execs never learn this simple lesson: unless you are a part of the movement, you will almost never represent it well.

Just look at what Hollywood attempts at commercializing punk rock. Try as they might through films like Valley Girl, the Ramones vehicle Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, or Times Square, it never looked nor felt like the real thing. Much of the music’s harsh edges were filed down and smoothed over, and the dangerous appeal of the look and attitude came off as near comical.

Thankfully, one aspect of punk’s ascendance—the DIY aesthetic that emphasized the creation of art on one’s own terms regardless of skill or resources—filtered into many different media of the late seventies and early eighties. So it was that the young people who aspired to be filmmakers were stirred to action by the eye-opening sounds of bands like the Sex Pistols, Television, Black Flag, and The Clash. It’s not a new story, but what these young auteurs captured on Super 8, 16mm and videotape was the pure, unfiltered soul and ideals of the punk scene.

For some, that meant just pointing the camera directly at the artists that inspired them. Don Letts, a DJ at the Roxy, a club in England that was friendly to punk bands, started filming the groups that would come in to perform there on his Super 8 camera. The compiled result, known simply as The Punk Rock Movie, stitched together pieces of performances from a murderer’s row of UK greats: Generation X, The Slits, Siouxsie and the Banshees, X-Ray Spex and Alternative TV. Interspersed are backstage moments capturing the sense of community among the musicians involved as well as the response taken by the establishment to this threat to the status quo.

Penelope Spheeris took a similar approach for her debut feature The Decline of Western Civilization. Again, the focus stayed primarily on the sweaty, physical live performances of West Coast punk groups like Germs, Fear, and Black Flag, but also featured interviews with fans and the editors of a punk fanzine to put the scene into cultural perspective. And like Punk Rock Movie, the camera becomes an active participant in the show, jostling with the crowd and trying to keep up with the manic energy going on around it. The editing too snaps in time with the quick tempos and fiery slashes of guitar.

Other films (D.O.A.: A Rite of Passage and Urgh! A Music War) also attempted to pull in as many acts as possible under a huge umbrella, but some honed in on one band or a small batch of groups that could be used as a lens to reflect the cultural upheaval happening all around them.

In the U.K., the obvious choice was the Sex Pistols, as it was that group that burned so brightly and fizzled out so dramatically, inspiring hundreds of young people to follow their lead. But Julien Temple’s film The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle took its title a little too seriously, providing a smattering of context and a whole lot of window dressing (animated sequences, Sid Vicious’s famous “My Way” video, etc.). Even a documentary/narrative hybrid like Rude Boy, which centered on The Clash, merely scratched the surface.

Punk was better served by documentaries like Another State of Mind, which followed Social Distortion and Youth Brigade, two Southern California punk bands, on their 1982 North American tour. As great as the performance footage is, the film is better viewed as a catalyst thanks to Youth Brigade leader Shawn Stern’s tireless efforts throughout to explain to the people they met on the road that punk was far more than how it was being portrayed in the media as a violent, nihilistic movement. X: The Unheard Music is ostensibly about the titular band, filmed onstage and off between 1980 and 1985. But W.T. Morgan‘s film also tells the larger tale of how punk upended the L.A. music scene and how that one explosion reverberated around the U.S. and beyond.

What The Unheard Music also exhibited was the influence on the avant garde art and film scene on punk. Morgan appropriated bits of travelogues about the glory of Los Angeles, used stop motion animation and still pictures, and even cast people in the film in small dramatic scenes. If there was ever a rulebook, its words had been cut out and reused as poetry and the rest burned for warmth.

This comes out most clearly in the narrative films that were born from the punk movement. Famed British Derek Jarman found a muse in the music when he directed his second feature Jubilee, a denatured fantasy about Queen Elizabeth I being transported to an apocalyptic future. Jarman doubled down on the influence by casting punk musicians like Adam Ant, Jayne County and Toyah Wilcox in key roles.

But whereas Jarman was working with a nice budget funded by the UK arts community, many American filmmakers were creating weird and engaging art with table scraps. L.A. scenester Dave Markey had a purported budget of just under $300 to create his sordid and hilarious Desperate Teenage Lovedolls, leaning on friends like the members of Redd Kross to act in this tale inspired by the creation and exploitation of the all-girl proto-punk band The Runaways. The lack of funds and the lack of acting skills by the film’s principles readily apparent in the film, but the raw energy and pleasure Markey and his crew bring to it can’t be easily brushed aside.

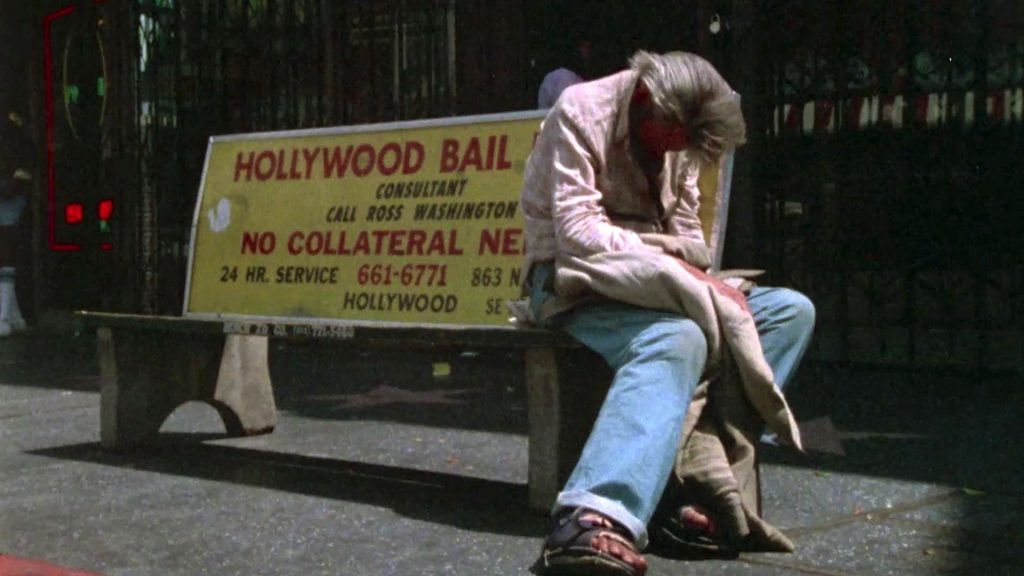

New York had its fair share of low-to-no budget filmmakers, including Nick Zedd, Richard Kern and Rachid Kerdouche, many of whom pointed their cameras at the seamier side of the downtown denizens with drug use and unusual sexual practices included in the mix. But even the films that were made with more professional equipment and actors still were sent through a skein of the avant garde and modern art worlds. Susan Seidelman‘s Smithereens, Edo Bertoglio’s Downtown 81, and Ulli Lommel‘s Blank Generation, some of the more well known films to emerge out of this world have a Godardian feel (choppy editing, ironic use of score) but expose its true inspiration by putting plenty of live musical performance onscreen.

What is interesting to note is how so many of the directors that were born from the punk movement ended up adapting their wares and visions for a more mainstream audience. Seidelman went on to direct everything from Madonna’s breakthrough film Desperately Seeking Susan to episodes of Sex & the City and a rebooted Electric Company; Spheeris helmed both Wayne’s World films; and Adam Small, one of the directors of Another State of Mind, created a number of comedy TV shows and wrote the screenplays for two Pauly Shore vehicles.

Those who stayed true to their punk roots, still making uncompromising art and working within the underground art world, remain below the radar to your typical moviegoer. But just as the music is still turning listeners heads inside out when they find it for the first time, so too are the reverberations from the vibrant and expressive films that emerged from that period still being felt today. They’ve often been adapted—the dizzy editing of Decline and The Unheard Music became the signature of MTV’s groundbreaking videos—but if these rough-hewn closet classics inspire some young filmmakers to take up cameras and make their own art, the ethos of the punk revolution will remain alive and well.