An early detail in Pulp Fiction quietly testifies to the film’s legacy. During the opening credits, after the prologue that features robbers Pumpkin (Tim Roth) and Honey Bunny (Amanda Plummer) planning a diner score that will come to have great reverberations on the story that follows, there’s an audible song switch on the soundtrack. Dick Dale’s surfer cover of “Miserlou”, which serves to prime audiences for the epic, unruly party that’s to follow, transitions into Kool and the Gang’s “Jungle Boogie,” and we can hear a player halted as if to switch records to set up that second song. That’s the key part. Movies before and after Pulp Fiction have long traded in elaborate soundtracks that serve to trigger nostalgia in viewers, but director Quentin Tarantino intentionally and bluntly highlights the manipulation to great, self-aggrandizing effect, telling the audience that he intends to do whatever he wants whenever he wants it.

“Jungle Boogie” plays at that moment because the director thinks it’s cool and because he damn well intends to make a cool movie. Tarantino directs the audience’s awareness toward his controlling hand as an artist, pulling the director-as-superstar formalism of something like Goodfellas into an explicit realm of narcissistic adulation. He’s rendering himself the star of his own film by providing his audience active CliffsNotes to his authorial choices, hoping to show that anything can happen in his art at any time. Tarantino’s auditioning for the role of bad boy auteur (a role pop culture granted him) with these infectious, gimmicky tics, and he’s also wearing his impressive-yet-studied cultural eclecticism on his sleeve as a badge of honor. The press often portrays Tarantino as the prototypical geek made good; as the video store clerk who shot all the way up to the big time, and Pulp Fiction shrewdly, and probably personally, works that narrative very deliberately into its fabric. The film is “about” essentially one thing: spinning geek esoterica into a tapestry of unchecked, unqualified, massively accepted awesomeness.

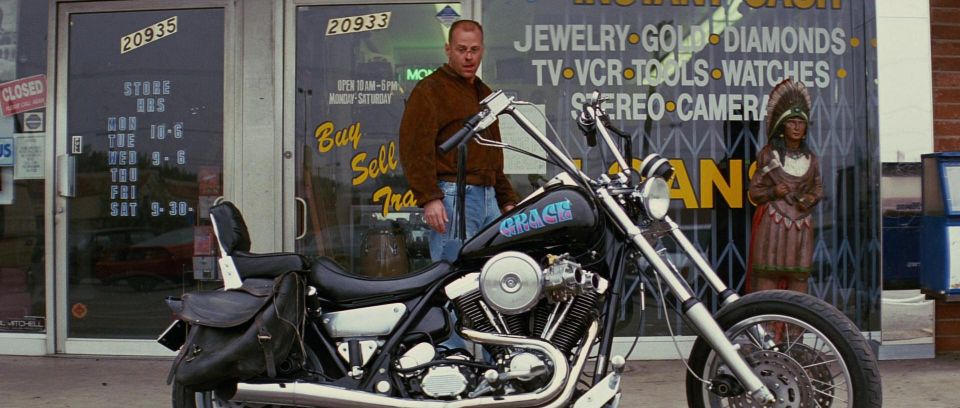

There’s a funny thing about awesomeness though: it’s slippery, subjective and, therefore, intangible. It’s a quality, not a thing, and the deliberate artifice of the record cue also signals Tarantino’s obsession with analogue, which provides, for him, a comfort of physicality that correlates with, and deepens, the refuge taken in the film’s famously unending pop cultural allusions. Jack Rabbit Slim’s, the restaurant that serves as a setting for the first story, which Vincent Vega (John Travolta) memorably deems a “wax museum with a pulse,” is densely alive with enough cinematic references to inspire a Taschen book of its own, and the stature of these references is often reaffirmed with the presence of objects that are informed, under Tarantino’s gaze, with totemic power: mannequins, posters, toy cars, skinny ties, Chevrolets, sunglasses, you name it. This setting also exaggerates another source of comfort that runs through the film: costume props, which allow the characters to turn themselves into their own, often desexualized, objects (specifically 1970s-style action figures), and to, again, offer tangibility to the abstractions of their tastes and personae. An Elvis song might be transcendent, cathartic art, but it’s floating in the ether, defined by our memory of it. A record of it is a thing. Tangible, grounded, real, capable of defining its possessor by virtue of his or her awareness and attainment of it. Real film, of which Tarantino is a very vocal real-life champion, is a thing, and the director even positioned it as the annihilator of the Nazi regime in his Inglourious Basterds.

For all of Pulp Fiction’s self-consciousness, the film’s reputation, with both admirers and detractors alike, as a meta-ironic work of too-cool-for-school-ness is exaggerated. The blended archetype characters and the wearying dramatic weightlessness are consciously achieved qualities, but they aren’t intended ironically. They just aren’t the focus of the film’s true reverence and awe, which is reserved solely for all the objects and the art they signify, and the personal transformations that they promise should you “get” them. Pulp Fiction is quite innocent, both obnoxiously and endearingly so. It’s undeniably a personal film, but it’s a personal ode to impersonality, to emotional evasion through stuff. (A rape is accorded less dramatic weight than a milkshake Mia orders at Jack Rabbit Slim’s; and most characters are most memorable for their hair styles.) Despite the bad-boy posturing, Tarantino’s eager to please as a filmmaker, exceedingly studied in his carefully planted cultural cues and instances of “outrage,” which serve to successfully distract from Pulp Fiction’s quite conventional theme of love thy brother.

It’s this obsessive objectification, which comes across as ironic distance from humankind (though a more accurate phrase would be “un-ironic indifference”), that renders Pulp Fiction retrospectively visionary. Tarantino’s tangibility anxiety, his need for stuff, anticipates the vast nervousness we now have as a culture, which is manifested by the MP3 players that are designed to resemble record players, or in the nationwide preoccupation with downtowns that resemble the downtowns of our movie-fed dreams, rich in artisan-driven stores and food that doesn’t come out of plastic with a sticker indicating corporate standards for preparation. This nervousness abounds both in the presence of “hipsters” and their (theoretical) rejection of corporate hive-mindedness, and in the inevitable antipathy that has greeted them (they have a similar stylistic tendency to render themselves action figures). With the technological rendering of most objects, stores and jobs moot, with cultural evolution steering us more and more toward a scenario in which we look at one device all day for every purpose while on the clock for an ever-merging few mega-corporations, we are feeling less and less tangible as people and even as consumers (with the Internet reminding us daily that we’re all the same in our niche “differences”). Something like Pulp Fiction, which has grown more and more pleasurable over the years, can almost play like disreputable porn that allows us to drink in the forbidden pleasures of tactile variety, whether it’s of humans, toys, objects, or outfits.

These anxieties, very real, very understandable, reactive to a culture that will only grow more suffocating in its all-inclusive anonymity, have led to the faux-boutique preoccupation outlined above, which extends to art, particularly to films that wear their clichés on their sleeve as license to indulge said clichés—a tendency that’s particularly noxious in the romantic comedy. Before a woman inevitably finds Mr. Right, she must pretend to assert her individuality by decrying society’s need for her to find Mr. Right, just to assure that all the proper and hip P.C. bells and whistles have been thoroughly blown through before we move back on track to 1950s Mom-and-Pop conformism. The modern version of this cycle, an extension of Warhol’s dubiously commercial detachment, started with Pulp Fiction and its love of objects over people, and its tendency to have stereotypes and clichés acknowledge, often wittily, the status of themselves as stereotypes.

Tarantino is a major artist, and that artistry was hinted at in Reservoir Dogs and confirmed with Jackie Brown, but his rebellious fetish poses, mostly in Pulp Fiction, Kill Bill, and Death Proof, are superficial and uncomfortably easy to commercialize. Tarantino has a reputation for resuscitating actors’ careers, but he also has a way of showing companies how to use kitsch to distract from their mercenary square-ness (the nadir of this being when a song from Kill Bill was used in a car commercial). Tarantino’s reach and influence as a director far exceeds the slew of shitty crime movies that ripped him off in the 1990s. Tarantino’s sensibility can be seen, perhaps coincidentally, in the films of Wes Anderson (who has become an expert deconstructionist of commercialist despair) and, less coincidentally, in movies like (500) Days of Summer and Lola Versus and Friends with Benefits. Pulp Fiction’s object-centric definition of cool-ness, which, lest we need reminding, is really a gussied up and self-delusional version of consumerism, can even be seen in sitcoms like the American The Office, which fused the comic awkwardness of the U.K show with the prevailing, ineffably American faux-ironic disenchantment that now governs every single-camera sitcom that congratulates young Americans for hating the conformity they support (with their dollars, with their debt, with their willing enslavement to the corporate drudgery that they pretend to mock) anyway.

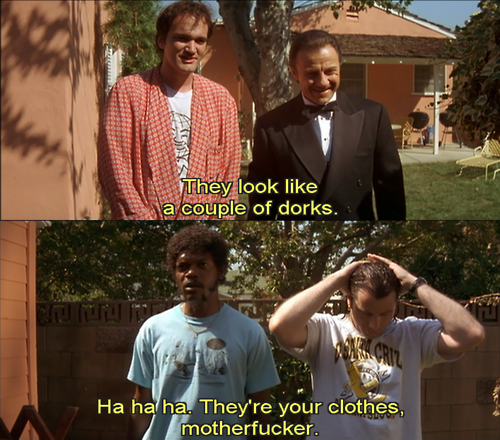

There’s conscious despair in Pulp Fiction’s addiction to iconography; hints that the characters are lost in role-plays they don’t even remember initiating. (That beautiful moment when Vincent blows Mia a kiss, after she’s gone into her house, safe from the sight of his unchecked sentiment.) But the film retreats anytime it threatens to get too vulnerable and dangerous, lapsing into stuff like the tedious subplot with Tarantino himself, a segment that, itself, plays like a sitcom. (Tarantino would commit to emotional transparency in Jackie Brown, and was promptly rewarded with box office receipts that were less than half of Pulp Fiction’s.) The beautiful cinematography that’s reminiscent of Technicolor and the obsessive slow-mo interludes that follow characters walking, or shooting up, addicted to their potentially coolness, suggest a level of melodramatic displacement that’s Lynchian (Blue Velvet is a major influence on Pulp Fiction) but directors, and pop culture at large, responded more to the chic irony. Most filmgoers left the theater looking for the tie-in CD to the brilliantly catchy soundtrack, rather than contemplating Vincent Vega’s rootless, pitiful downfall. That’s not necessarily Tarantino’s fault (though he encourages this sort of superficiality in his reliably obnoxious interviews), but a specific, insidious consumerist ripple expanded from Pulp Fiction’s metaphoric stone nonetheless. It helped to erect a wax museum that few wish to leave.