That wondrous invention, the motion picture, has always been equipped better than any other medium to fulfill one of mankind’s most basic if perverse desires: To face our worst fears, albeit while comfortably secure no actual harm will befall us. Early nickelodeon audiences actually ducked when a bad guy at the end of The Great Train Robbery fired a pistol blank at “us,” terrified then thrilled to experience that all-American fate of being shot dead by an outlaw varmint without actually dying.

Soon even little children understood that these flickering images were simply illusion, however, and having stuff aimed or thrown at the camera ceased to be an automatic thrill. (Not that that stopped the first great wave of 3-D cinema, or its current vogue.) Movies would have to plumb deeper to pleasurably tweak that exposed nerve of fear, moving past everyday, real-world perils toward the actual stuff of nightmares—those private terrors that haunt our sleeping hours from childhood, defying simple explanation but begging interpretation with their funhouse distortions of violence, sex, anything disturbing and/or shameful. The trickery implicit in and available to this new medium made it an ideal vehicle to conjure superstitions, summon monsters of the id, invent its own mythologies of hellish torment, suffocating dread and unnatural enemies.

Thus the horror film was born—though there were plenty of precedents for it in other art forms, none so exhaustively feasted on ghastly fantasy’s potential before or ever since. As a genre, horror continues to get disrespected, taken less seriously in some quarters both popular and critical. Yet what was once a rare exercise in slumming for major Hollywood studios is now a staple production, not infrequently involving front-rank directors and stars. A taste considered anything but universal, causing very few horror films to be made outside a handful of countries, these films are now so widespread that you’d be hard-pressed finding a nation that hasn’t produced its own slasher or zombie flick in recent years.

Early Cinema’s Haunted Screens

Cinema’s earliest flirtations with the macabre were as vaudevillian yet gentlemanly as their depiction in Scorsese’s recent Hugo: The delightful parlor tricks of Georges Méliès, that French pioneer whose mini-spectaculars were terrorizing humanity with ghastly phenomena as early as 1896. That year’s The Haunted Castle alone afflicted its protagonist with vampire bats, skeletons, witches’ cauldrons, white-sheet ghosts and more in under four minutes. It was all in good fun, though, meant to be taken no more seriously than a carnival spookhouse.

Attempts to bring the uncanny to celluloid life in earnest didn’t commence until the 1910s, duly kicked off by the first of umpteen attempts to film Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. (With Boris Karloff’s 1930s incarnation still our dominating imagination, this Edison Company vision of the Monster looks more like a cross between the Hunchback of Notre Dame and Bigfoot.) The decades also saw early depictions of Dr. Jekyll, the Golem, and other classic literary menaces.

But the first great horror movie was resolutely original, modernist, even avant-garde: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the 1919 film that was revolutionary in form and content. Attempting to place us in the mindset of the insane, it used distorted settings, costumes, and makeup to hypnotic, dislocative effect, introducing German Expressionism—a post-World War I artistic movement encompassing several visual media—as a singular cinematic style influential throughout the Western world. (It was largely responsible for European directors being considered more “artistic” than their U.S. equivalents during the silent era. As a result many were lured to Hollywood studios, then promptly robbed of the imaginative license that had made their talent coveted in the first place.)

The use of German Expressionism in films such as ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ was largely responsible for European directors being considered more ‘artistic’ than their U.S. equivalents during the silent era. As a result many were lured to Hollywood studios, then promptly robbed of the imaginative license that had made their talent coveted in the first place.

Some of the next decade’s great achievements—in horror films or in films, period—followed in those same boldly stylized footsteps. (Aspects of the Expressionist aesthetic would strongly resurface years later with the post-WWII crime melodramas we now call film noir.) Enduring German classics of the period include Paul Wegener’s 1920 The Golem, the most famous version of that tale about a vengeful giant clay statue; Nosferatu (1922), F.W. Murnau‘s haunting, unauthorized (and thus legally suppressed for a time) version of Dracula; Arthur Robison’s 1923 psychosexual nightmare Warning Shadows; Caligari director Robert Wiene‘s possession thriller The Hands of Orlac (1924); and from the same year, Paul Leni’s baroque horror omnibus Waxworks (1924). Elsewhere in Europe, Swede Benjamin Christensen contributed the extraordinary Häxan or Witchcraft Through the Ages, a quasi-documentary with myriad staged sequences documenting the history of the occult so vividly that for many years the film was most often seen in drastically cut form. Danish director Carl Dreyer belatedly ended horror’s silent era—forced to use sound, he nonetheless kept dialogue to a bare minimum—with 1932’s dreamlike Vampyr, a flop that later generations would pronounce a hypnotic masterpiece.

After the decade’s midpoint nearly all these directors found themselves answering the siren call of Hollywood, most for relatively brief stays that nonetheless resulted in striking features like Paul Leni‘s The Cat and the Canary and Benjamin Christensen’s Seven Footprints to Satan—two in the “haunted house” genre that was already usually done tongue-in-cheek, with rational rather than extra-normal explanations at their close.

American audiences of the time more or less demanded such denouements. One thing that separated audiences of the 1920s from those before them was their proud, insistent belief in progress, and skeptical dismissal of any old “hogwash”—like superstitions and folktales. (Draw what conclusions you may from our own era’s renewed, unironic appetite for filmic monsters, fantasy worlds, and superheroics, coinciding as it does with increased religious fundamentalism and scientific apocalypticism.) The visual intoxications of those above-named European productions may have allowed suspension of disbelief, but in general Yank viewers wanted their thrills at least marginally real-world credible.

It was the unprecedented mass horrors of World War I, in a way, that paved the way for the first great U.S. horror star. The child of deaf parents forced into film from theater after a grotesque scandal (his first wife failed at suicide but succeeded in ending her singing career by ingesting mercury chloride), Lon Chaney was a master of pantomime and makeup who achieved fame portraying characters suffering under some grotesque physical disability (or ability): A contortionist in The Miracle Man, legless gangster in The Penalty, razor-toothed faux vampire London After Midnight, armless circus knife thrower (!) in The Unknown, and so forth—to say nothing of his most famous roles as The Phantom of the Opera and The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

A fine actor, Chaney (who died of lung cancer in 1930 at age 47, after making his sole “talkie”) almost always lent his ostracized figures a deep strain of pathos. It’s been speculated that the mixed pity and repulsion they engendered was somehow cathartic for audiences working through their own issues: The war had sent home a great deal of maimed and disabled soldiers who had trouble fitting back into a rapidly changing modern society.

Sound, which in very short order reshaped the whole industry after the success of 1927’s The Jazz Singer, initially seemed to leave little room for horror. Underdog studio Universal was considered by many to be taking a stupid risk filming the literary chestnuts Dracula and Frankenstein in 1931. Unexpectedly, both became sensations, making respective stars of Bela Lugosi (who’d played the Count on stage) and hitherto little-known Boris Karloff. Their directors, erstwhile Lon Chaney collaborator Tod Browning and British expat James Whale, also benefited from the spectacular success—though like the actors, they grew frustrated by being “typed” as horror/fantasy specialists. (For that and other reasons, each found their careers pretty well over by the decade’s end.)

Underdog studio Universal was considered by many to be taking a stupid risk filming the literary chestnuts ‘Dracula’ and ‘Frankenstein’ in 1931. Unexpectedly, both became sensations, making respective stars of Bela Lugosi (who’d played the Count on stage) and hitherto little-known Boris Karloff.

Though the resulting horror vogue spread to all major studios, Universal continued leading the pack, sticking with a good thing through such subsequent classics as The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), The Black Cat (1934), The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Dracula’s Daughter (1936), and The Wolf Man (1940, with Lon Chaney Jr. in the title role).

Drive-ins, Teenagers, and the Atom Bomb

The arrival of the Production Code in 1934 made it more difficult to get macabre subjects past the censors—some of the “pre-Code” horror films had already been banned outright as too grisly in other countries, notably Great Britain. That factor, plus changing audience tastes, contributed to a gradual juvenilization of the form. The 1940s were a low point for the genre: Monsters and fantastical themes were relegated to kiddie serials and Poverty Row “B’s,” when not simply milked for comedy. Universal’s biggest “horror” hit of the decade was 1948’s strictly-for-laughs Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, which kickstarted a whole series of spoofs starring that lowbrow duo.

Among precious few exceptions, the most significant were producer Val Lewton’s innovatively suggestive, atmospheric, psychologically complex thrillers for RKO—some overtly supernatural (like Cat People or I Walked With a Zombie), some less so (Bedlam, Isle of the Dead). But despite their unusual finesse and consistent profitability, at the time they were regarded as little more than ghoulishly effective potboilers. When a supportive studio executive died in 1946, Lewton’s services were no longer desired; he suffered a string of further career disappointments before dying himself just five years later.

Three things can be safely said to have come to horror’s rescue in the 1950s: Drive-ins, teenagers, and the atom bomb. The first two were linked, in that the postwar era’s boom in prosperity, car culture, and babies made it logical that the movie industry should start catering to young adults in need of an entertainment (and snogging) space away from prying parental eyes. Drive-in theatres, which began surfacing as early as 1933, provided a madly popular solution.

Young patrons didn’t want heavy drama, or anything else that would require their whole attention. Better that the films be formulaic genre items allowing plenty of viewer makeout time between periodic jolts of action, scares, rock music, and sex appeal. New studios like American International Pictures emerged explicitly to fill that demand, cranking out umpteen low-budget exploitation flicks that sometimes launched whole mini-genres (the “beach blanket” musical, biker flicks, etc.).

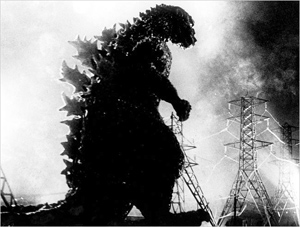

The A-bomb—along with the Cold War and its U.S.-vs.-U.S.S.R. space race—changed the content of horror films, which now often incorporated sci-fi elements. Monsters were no longer created by occult forces or mad scientists, but by the imagined mutating aftereffects of radiation exposure, or by malevolent aliens bent on conquering Earth. (The latter were often Martians standing in for the Communist Threat.) Thus arrived The Thing (from Another World), memorably remade decades later by John Carpenter; The Creature from the Black Lagoon; giant ants, tarantulas, crabs, shrews, blobs, and so forth. (This latter trend would arguably reach its lunatic apex with 1972’s Night of the Lepus—yup, giant killer bunnies.) Adding a foreign counterpoint in 1954 was Godzilla, a serious commentary on Japan’s nuclear trauma that proved so popular (both at home and in much-edited versions abroad) that it launched a still-active series too silly and child-targeted to be taken as horror.

Godzilla cast a long shadow in other ways, too: It was one of the first films since the silent era (which naturally suffered little from language barriers) to be widely, popularly exported. Soon several other nations’ movie industries were creating product with a particular eye toward breaking into the lucrative American market, movies whose basic appeal—i.e., sex and violence—translated as easily as their dubbed dialogue. Horror was a natural fit, since little star power or production expense was required—audiences didn’t expect spectacle, just some cheap thrills. On the other hand, Hollywood did strain some muscles trying to keep viewers away from that damned new domestic usurper, television, deploying everything from CinemaScope and 3-D to the goofy gimmicks of horror specialist William Castle in order to create the “you-can’t-get-this-free-at-home” experiences. The era’s most famous original 3-D film House of Wax as well as several Castle thrillers made suave yet campy Vincent Price the decade’s only notable new U.S. horror star.

The A-bomb—along with the Cold War and its U.S.-vs.-U.S.S.R. space race—changed the content of horror films, which now often incorporated sci-fi elements. Monsters were no longer created by occult forces or mad scientists, but by the imagined mutating aftereffects of radiation exposure, or by malevolent aliens bent on conquering Earth.

An early but aggressive player in realizing the horror genre’s border-crossing appeal was Mexico, whose horror contributions ranged from the atmospheric to the strange and outright silly, not least because they so frequently featured masked wrestling hero Santo. Revival of traditional supernatural suspense (and its brand-name villains) was spearheaded by hitherto horror-skittish England and an upstart studio named Hammer. It was 1931 all over again, albeit in color with a lot more blood, as 1957’s The Curse of Frankenstein and the next year’s Horror of Dracula did for Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing and Hammer what those stories had once done for Lugosi, Karloff and Universal. (Naturally enough, the latter studio handled U.S. distribution.) Like their predecessors, those actors too would eventually feel suffocated by their identification with the genre—but they undeniably brought it more skill and nuance than it had seen before.

‘Psycho’ Opens Floodgates

The early Hammer films were considered rather shockingly violent, and with all those Victorian maidens’ heaving, low-cut décolletage as Dracula caved to bloodlust, extremely sexy. But what kicked off the whole 1960s “violence in cinema” debate in earnest was a movie from a prestige director who’d always specialized in suspense but never lowered himself to vulgar horror. Psycho, which fittingly started off a new decade of bloody unrest both on and off-screen, looked like decidedly minor Hitchcock with its modest scale and by now almost incongruous B&W photography. Then Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane—the sympathetic protagonist we fully expected to stick with to the end—was abruptly, savagely, obscenely stabbed to death in her room shower at the Bates Motel, just 46 minutes into the nearly two-hour the film. A new era in horror had dawned.

It was nastier, more brutal, more interested in abnormal psychology than the supernatural, and arguably more misogynist than horror had been before. Partly this was due to the gradual crumbling at last of the Production Code, which had required all films to adhere to one family-friendly standard for acceptable content. By the end of the 1960s it would be long gone, replaced by the current MPAA system of age-restrictive ratings.

The floodgates were opening, and there would be no turning back. It would take a while for extreme gore (pioneered by Herschell Gordon Lewis’ subterranean 1963 Southern drive-in cheapie Blood Feast) and graphic sexual content to penetrate, ahem, the mainstream. But the sexual undercurrents in so much horror would never again be as discreet as they had been, liberated by a “new frankness” reflecting modern audience sophistication, cynicism, and impatience with censorship.

The new horror of the ’60s was nastier, more brutal, more interested in abnormal psychology than the supernatural, and arguably more misogynist than horror had been before. Partly this was due to the gradual crumbling at last of the Production Code, which had required all films to adhere to one family-friendly standard for acceptable content. By the end of the 1960s it would be long gone, replaced by the current MPAA system of age-restrictive ratings.

In the short term, Psycho had the effect of triggering a bazillion “psychological thriller” imitations. Many centered around fragile young men with mother complexes—just like Norman Bates—who turned out to be killing attractive young women in sexual frustration, confusion or something. (Such was the movie psychology of the era: Repressed homosexuality was often taken for granted as a cause for murder—because gays want to be women, right? And the best way to become them is to kill them, right? This kind of thinking would surface in films as late as 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs.) Pretty girls spied upon, undressing, running, screaming, bleeding, dying…this entertainment staple really came into its own in the 1960s, and has been with us ever since. Just try to come up with a few serial-killer type movies in which all the victims are male. Bet you can’t count past the fingers of one hand.

A curious sidebar of the psycho craze didn’t involve comely youth at all, however: When 1962’s Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? united veteran stars Bette Davis and Joan Crawford (who hated each other) as sisters in a grotesque Grand Guignol of madness and murder, its enormous success created a whole subgenre of once-glamorous Hollywood royalty playing crazy old hags or infirm victims. Lasting about a decade, this vogue’s campy highlights include Crawford solo blowout Straitjacket and Tallulah Bankhead as the mother-in-law from hell in Die! Die! My Darling.

These weren’t the only fairly respectable, bigger-budgeted horror titles of the era. Between West Side Story and The Sound of Music, A-list director Robert wise made upscale-spookhouse tale The Haunting (1963); another Academy Award winner, Deborah Kerr, starred in the classic ghost story The Innocents (1961), based on Henry James’ novella The Turn of the Screw. True-crime horror arrived in the form of major Hollywood productions In Cold Blood and The Boston Strangler. Even bottom-feeding American International let Roger Corman wax more ambitious on a series of stylish Edgar Allan Poe adaptations (usually with Vincent Price), while cut-rate indie productions occasionally surrendered up something special like Herk Harvey’s dreamlike original Carnival of Souls or Dementia 13, an unusually potent Psycho knockoff directed by an unknown named Francis Ford Coppola.

Universal Shock Appeal

Abroad, things got even more interesting. Horror was now perhaps the most widely exportable genre, encouraging the manufacture of myriad mostly cheap ‘n’ cheesy exercises from Mexico, now joined by the Philippines, Spain and Italy, among others. Hammer stuck to its Gothic formula, to eventually diminishing returns (by the late ’70s they’d stopped making features, re-starting the brand just recently with 2012’s The Woman in Black), but the Italians innovated. Mario Bava, now considered one of the great horror directors, created a rare female horror star in Brit Barbara Steele with 1960’s witchy Black Sunday. He then pioneered the “giallo” genre of gory murder mysteries in 1964’s gorgeously shot murder mystery Blood and Black Lace. (Along with the latter, one can view Bava’s 1963 The Whip and the Body, a perverse tale with Christopher Lee, was closer in feel to Corman’s Poe films.)

Prestigious European “art house” directors occasionally dipped into horror, notably with the 1968 omnibus Spirits of the Dead, which consisted of three Poe-derived stories directed by Roger Vadim, Louis Malle and Federico Fellini, involving such major international names as Brigitte Bardot, Jane Fonda, Alain Delon, and Terence Stamp. After making a splash with his Polish-language films, Roman Polanski went international with the exceptional psychosexual horror Repulsion (1965), then a few years later gave Hollywood its biggest mainstream horror success yet in Rosemary’s Baby (1968).

From Japan, which had started exporting prestige productions in the 1950s, there started to issue a series of visually impressive ghost stories like Kwaidan and Onibaba, though arguably such macabre whatsits as Jikogu (Hell) and Blind Beast proved more interesting. The freewheeling marketplace of the era allowed just about any quasi-horror weirdness to be profitable so long as it didn’t cost much, leading to the emergence of such enduring cult figures as Brazil’s José Mojica Marins aka “Coffin Joe,” Spain’s Jess Franco and Paul Naschy, France’s Jean Rollin, and many more.

By the dawn of the 1970s movies had undergone changes more drastic than any since the switch from silents to sound. Widely accessible hardcore porn was still a couple years away, but otherwise most of the barricades had fallen in terms of depicting graphic violence, nudity, and “mature themes.”

Needless to say, filmmakers serving the exploitation markets took their new freedom and ran with it. Much has been made of the bitter Vietnam War era disillusionment as a political undercurrent running through the most influential independent U.S. horror films of that period, all by youngish directors identifying with the counterculture: George Romero’s 1968 Night of the Living Dead—wellspring of a zombie craze that’s stronger than ever—Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left (1972) and The Hills Have Eyes, Tobe Hooper’s 1974 Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and other less famous but equally distinctive titles. Offering his own weird parallel series of horror films queasily obsessed with the mutating body as symptom of a sick society was the Canadian David Cronenberg (They Came from Within, Rabid, The Brood).

The freewheeling marketplace of the post-Vietnam era allowed just about any quasi-horror weirdness to be profitable so long as it didn’t cost much, leading to the emergence of such enduring cult figures as Brazil’s José Mojica Marins aka ‘Coffin Joe,’ Spain’s Jess Franco and Paul Naschy, France’s Jean Rollin, and many more.

Meanwhile the same-old was still being churned out, from the ebbing Hammer horrors to a new wave of nature-gone-wild thrillers that replaced 1950s radiation-giganticism with creatures created or simply enraged by our pollutive mistreatment of Mother Earth (Frogs, Dogs, Day of the Animals, Lost Weekend, Prophecy, et al.) Italy continued to produce some of the more lurid as well as distinguished exercises in gory suspense, with Dario Argento taking over from Mario Bava as the most stylish auteur working in giallos (Four Flies on Grey Velvet) and supernatural shockers (Suspiria), followed by Lucio Fulci and numerous others.

The Age of the Slasher

Despite all this activity, with rare exceptions horror had remained looked-down-upon as strictly “B” fodder by the major studios, despite occasional mainstream successes like the rat-attack-driven Willard (1971) or Brian DePalma’s 1976 Carrie, the latter the first of many, many Stephen King adaptations. But three films of the decade disturbed the wisdom of that attitude. William Friedkin’s 1973 The Exorcist, a deadly serious tale of demonic possession from a bestselling novel, was a pop-culture phenomenon that earned ten Oscar nominations (winning two).

Two years later Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, of which nothing special had been expected, made more money than any movie had previously with a beautifully handled but very basic big-hungry-thing-eats-people premise. (Its unprecedented box-office takings, however, would be trumped all too soon by Star Wars.) Then Richard Donner’s critically dissed but enormously popular The Omen (1976) reinforced the notion that respectable folk could make (and attend) a high-end horror movie without disgracing themselves.

These films were all imitated to varying degrees of shamelessness for years. But the two films that would most influence horror going forward were, respectively, anything but prestigious, and not even “really” a horror movie (or so its makers claimed).

The “slasher” movie had more or less existed before enterprising B filmmaker John Carpenter made 1978’s Halloween, its essential parameters established by cult objects like the aforementioned Blood and Black Lace and the Canadian Black Christmas (by the future director of Porky’s!). But the ingeniously simple gist of youth (primarily female) being stalked and slain by an Unstoppable Killing Machine was Halloween’s own to set in stone. The 1980s were the Age of Slasher, inciting debates a