Few can write about Pasolini without recalling his poetic/prophetic death. Found repeatedly run over by his own Alfa Romeo at the age of fifty-three, his murder is a permanent cold case. His accused killer was a “rent boy,” a gigolo with ties to the neo-fascists, thus coloring the tragedy with political implications. The hustler was from a residence like those Pasolini made spare poetry out of in films like Momma Roma (about to play in the San Francisco Bay Area as part of a touring Pasolini retrospective that will eventually hit Washington, D.C., Ohio, and Toronto, among other destinations). The marshy projects Mussolini erected with foundations full of utopian promise were indeed home to great drama, struggle and squalor. Pasolini recast all the traits of classic tragedy in post-war Rome; when hasn’t Rome inspired such narrative heights?

Pasolini published frequently and his first poems were in the Friulian dialect, one he adapted when living in Casarsa with his mother. She was born in Friulia and his affection for the place seemed analog to his affection for her. Part of his hope in publishing in the dialect was to help the peasants who spoke it be “historically aware” and he’d write later about the danger of losing the native languages to the bourgeois standard Italian audible everywhere there was TV or radio. His attachment to native traditions (like dialects) was a constant fixture in his works, and often resembles internal conflict. He is, after all, a modern man aware his is an old culture, adjusted with time. This is precisely the romance that leads to activism. Relentlessly, Pasolini is inside and outside.

In 1949, years before his first film, officials charged him with “corruption of minors and obscene acts in a public place;” the crimes were unclear, their sexual orientation were quite clear. Pasolini left Casarsa rejected also by the Casarsa branch of the Communist Party, but this didn’t stop his political efforts. Pasolini was a homosexual and a Catholic—this is one of many formative anecdotes that describes a man beholden to and fascinated by contradiction.

While his contemporaries were making quiet epics about soul-eroding industrialization (Antonioni) or ballsy fables that straddled “popularity” in the past and the present (Fellini), Pasolini was dipping his pen into political inkwells, often making enemies with its strokes. It’s impossible to contain his contradictions with a phrase, but we can see in his films a relief in ancientness, a reliance on the power moves of radical activism, and an eventual relenting to the necessary and universal truth that we are all made of flesh. We can all be cleansed by soap—and soap opera.

His films have been written about as if he is has his own genre arc: his early romances about the subproletariat were dubbed “The National Popular Cinema” (Accattone, The Gospel According to Saint Matthew), while a rash of works critical of the bourgeoisie were called “The Unpopular Cinema” (Teorema, Medea). Those frustrations aside, he made his “Trilogy of Life” (Arabian Nights, The Canterbury Tales, The Decameron), a winding stream of vignettes tied loosely together by a shared appreciation for sex and scat jokes. He followed the trilogy with Salo, which called an “Abjuration of the Trilogy of Life” and seems to distill his disgust for the elite with his appreciation for the rolling narratives of towns, houses, timelessness. Even with such varied subjects, all his work feels of a piece.

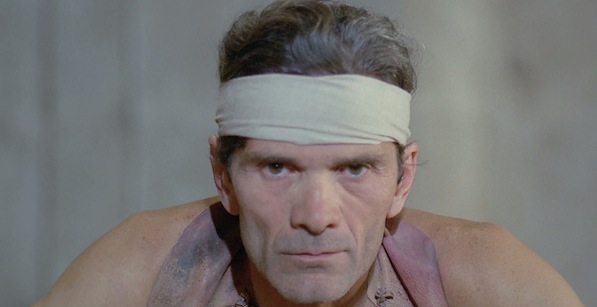

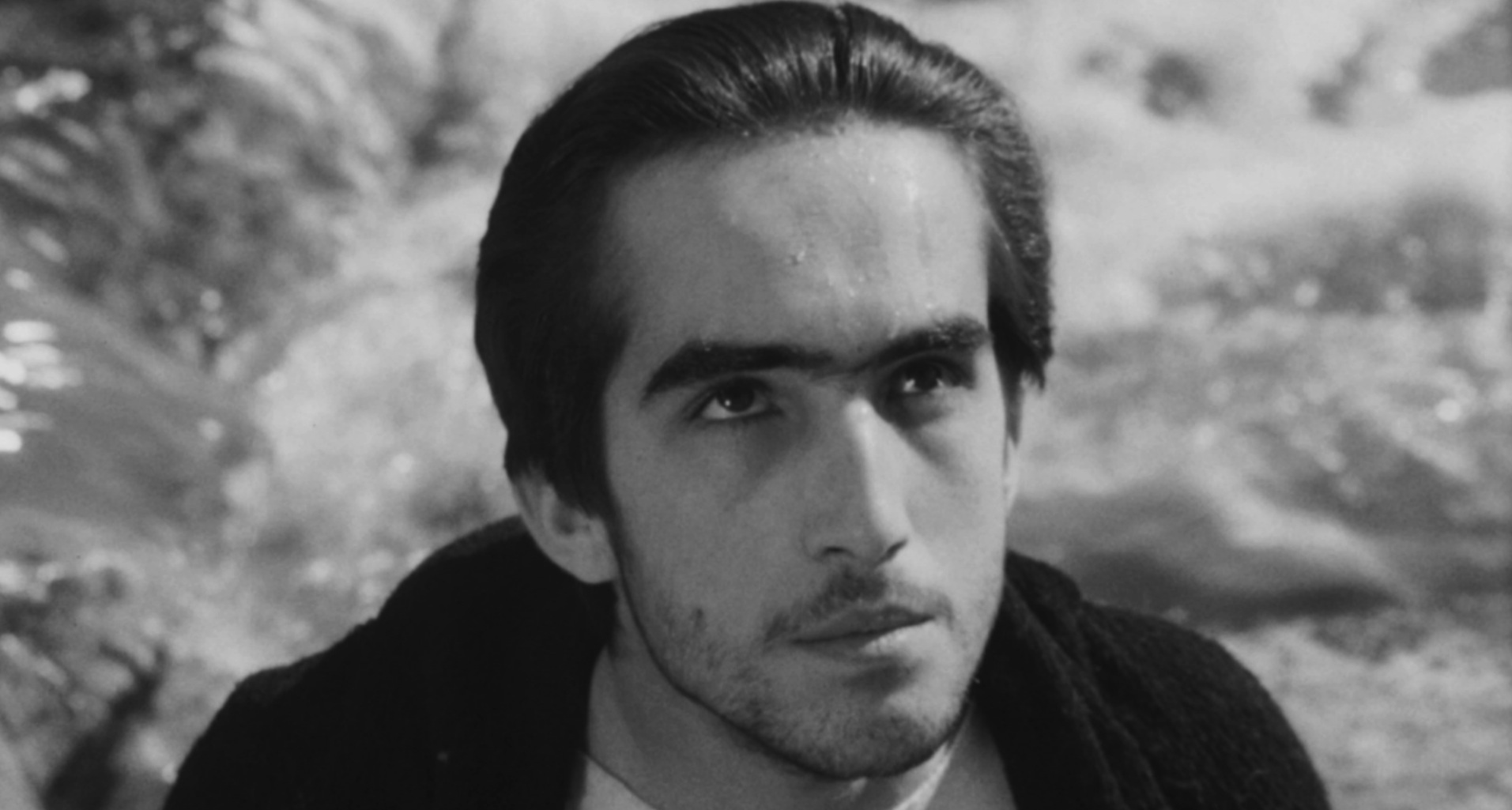

In Pasolini’s second film, Anna Magnani plays Momma Roma, a life-loving prostitute who regains her teen son after years of estrangement. He’s almost out of the nest when Momma brings him to a Roman project where the kids are higher quality and she’s far enough from the oldest profession and its army of arm-twisting pimps to be a good influence on the boy.

Pasolini treats her prostitution like a brand of martyrdom. He’s not alone: Pedro Almodovar turned Penelope Cruz into a mother and a saintly streetwalker for Trembling Flesh. Kenji Mizoguchi, whose sister financed his film school education plying “the trade,” would feature prostitution as an apologetic homage. Pasolini’s fascination with the mother/whore is the product of the same poignancy: these women are powerful because they give themselves for their children. It’s biblical they should also be rebuked for their lack of chastity—especially by their own children.

Not all women are created equal: Ettore’s love interest is the girl “all the boys go with.” When her baby becomes terminally ill she shakes off her sadness by helping Ettore shake off his virginity. For Pasolini, sex was a mortal sin of great consequence—even if he sort of didn’t believe it counted in purgatory.

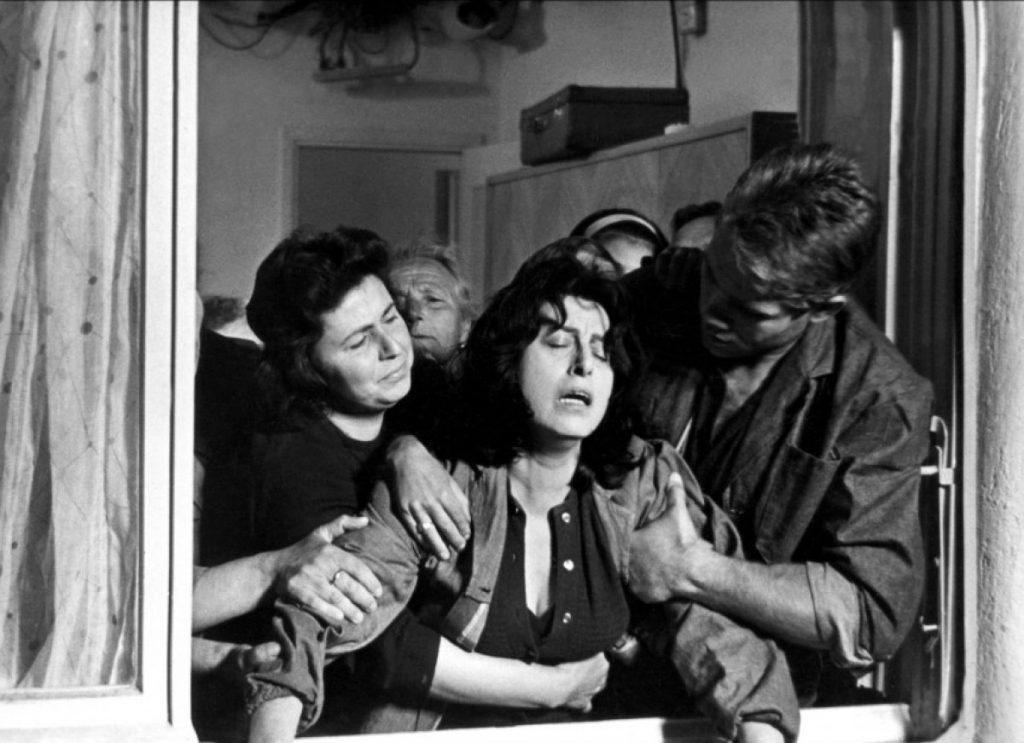

Madea, another film in the traveling retrospective, is a masterstroke. Pasolini cast opera singer Maria Callas as the glamazon sorceress who silently strikes fear into the hearts of kings. Naturally his retelling reveals some modern sensibilities but the story is part of an oral tradition and known to many changes. He begins with Jason’s pursuit of the Golden Fleece, which Medea steals and delivers to him. Their romance is brief and jarring. They have two children. Medea realizes her husband is remarrying despite their union and she prays to regain the contact with the old ways she once had. Her response is serene, even sweet despite her severity and mascara. She tries to sway Jason, is generous to his new bride and honorably requests she and the boys not be thrown from their home, abandoned to live like gypsies or worse. Ultimately the film sides with the murderess, and almost explains the inexplicable: what circumstance could force a woman to kill her own babies? Her words are eerie, surreal, too wise to bear: “Now nothing is possible anymore.”

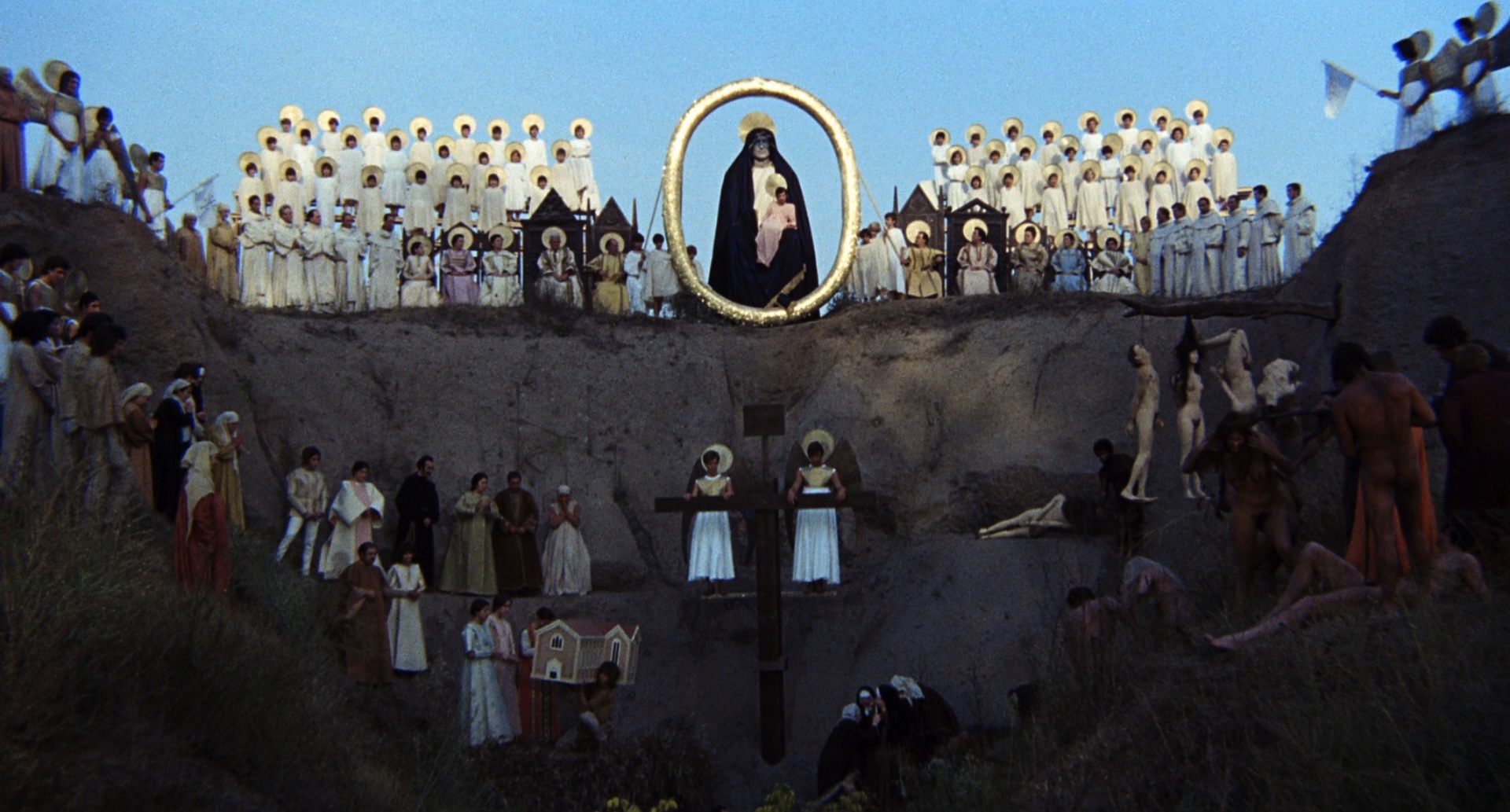

Pasolini’s previous reverence for the children and family unit (if even perverted in Teorema or inverted as in Oedipux Rex) moves aside for the Trilogy of Life. Primarily based on classical texts, these stories escape politics and the present day at once. The Decameron jaunts through the Pasolini’s imagining of Bocaccio’s 14th century. Nine vignettes (anecdotes in their way) transform Naples into the world’s raunchiest high school, full of sexually curious nuns, affectionately lecherous wives, double crossed city folks and comically swindling clergy. If Grease had been at a Catholic school (and been more liberal about skin show) it might resemble The Decameron—without the singing, of course. Its sweetest suggestion (offered by a ghost returned from purgatory) is that perhaps the church made sex as a mortal sin as a gift—isn’t the forbidden fruit the sweetest?

Pasolini melted into The Canterbury Tales—the juvenile humor, the ribaldry, the primitive absence of underclothing. He nearly leaves the frame story to the title—the fact these lechers and thieves come from upright, church-going citizenry is not a great concern to him; he prefers the universality of the stories and chooses them on those grounds. England has never seemed so whimsical as when a preacher enters hell, arms heavy with the food gifts he’s been hoarding from his brethren. The devils are naked men, painted brightly as if landmarks or evil tour guides for their respective corners of hell. When a giant red ass shows us where the bad clergy are kept, you might have a flashback to Being John Malkovich’s Jersey Turnpike. Pasolini sees Chaucer’s hell a burlesque of night terrors; if this Hades is a reason to avoid sin, Sesame Street is a reason to avoid meeting your neighbors. Cruelty is vile, contemptible, loathsome, but sin is spirited! It’s busting with vitality, despite the fact it’s occasionally destructive—there is justice (that fat friar was certainly scared) but this ancient, universal world is all a mess of enthusiastic wrongness and titillating piety. True malevolence will be dealt with later.

Arabian Nights follows the loosely gathered tales of the Middle East’s canonical 101 Nights. I presume Pasolini found Aladdin and Scheherazade too G-rated to include. Instead we have a surrogate frame story, begun by an enigmatic captive, a slave-girl whose self-possession knows no shackles: she is owned by none but herself (Eritrean actress Ines Pellegrini). When she’s stolen from her master her story spools out into the tales of others. She meets an unnamed Ali Baba, is anonymously crowned king and married and hears the tale of a man smitten by another on his wedding night. We travel from story to story like sands travel the wind. There’s no church to impugn Pasolini’s carnal displays (which are many) but the rules of the Trilogy favor the cheerful—the indomitable slave, the unsinkable victim of robbery, the Chaplinesque fool in the stockade still smiles because…why not? Pasolini is from the culture that described our pain and pleasure in the afterlife as “The Divine Comedy.” These sorrows brighten joy as a pinch of salt sweetens sugar.

One can say “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery” but Pasolini didn’t feel so great about the copycats his Trilogy inspired, in part because the aspect those knockoffs were keenest to replicate were softcore. It’s ironic since the trilogy embodies a purity that, perhaps, none could fake. This is why his last film, Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom, is the “Abjuration of the Life Trilogy,” but that’s clearly not the only reason.

Salo is an angry radical gesture, a film so absorbed by its disgust it can’t muster either the scent of happiness or relief. There is no joy in this castle of kidnapped virgins and highly-paid hookers. The men representing Mussolini’s ruling class delight in rape, intimations of pedophilia, shit-eating, murder. Their lust is for power but sex is their misused pathway to it. What are the men making? Why, an aberrant heaven in their shabby villa! Until they grow murderous the penalties they use to threaten the virgins are funny to them—the only crime punishable by death is screwing out of your social class. People have written about Salo as the work of a broken man, an artist aggressively rooting through his disappointments in society, which were also ammunition for his work. Regardless people outside of the industry knew the controversial film was in production and, it is rumored, reels were stolen from the film. Testimony from the director’s friend indicated that the night he was murdered Pasolini was going to meet with the thieves.

The teenage rent-boy who confessed to murdering Pasolini in 1975 recanted his confession twenty-nine years later, saying it wasn’t he who killed the “filthy communist,” it was three men with a southern accent.

The Pasolini exhibition will travel to UC Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archive from September 20 to October 30, to Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts from September 27 to October 27 (shipping films back and forth), to Washington DC’s National Gallery from November 2 to November 30, to Washington’s American Film Institute right after, to Columbus, Ohio from January 9, to February 25, 2014 and later to Toronto (dates to be confirmed).