When you think of “body horror” in the movies, what comes to mind? Cronenberg’s The Fly, or Lynch’s Eraserhead? Maybe Tokyo Gore Police, Ichi the Killer, or Tetsuo: The Iron Man? These movies prey on the deep, abject fascination we have with our bodies, and with boundaries: what belongs inside and outside, the chaos of transformation, the wet nightmares that live beneath the concealing smoothness of our skin, and so on. Everyone is, on some level, aware of their body’s potential to rot, to recede, to revolt, to reveal.

The real revelation of body horror is the fear of being trapped in one’s own skin, prisoner to its whims instead of in control of its presentability, hygiene, and function. The brain is, without question, a part of the body, but is the mind? Often, horror conventions use in-scene reactions as a cue for the response we should have — gasping, recoiling, screaming, and running away. But every once in a while, the reaction is instead one of confusion, denial, or even ridicule, implying that the disease is in the mind, not the body, and therefore that the sufferer is an unreliable narrator. This “phantom body horror” shifts the blame out of the unruly body and into the untrustworthy mind, and while it is not nearly as visceral as its traditional body horror counterparts, it is often just as emotionally harrowing. Thus, this trope functions as a way for directors and even genres not normally associated with the body horror canon to explore powerfully abject themes.

For example, Todd Haynes is certainly not someone who might come to mind when considering the prominent directors of this subgenre, as his films tend to focus on society and the psyche. But in his 1996 film Safe, his protagonist, an upper-middle-class housewife played by Julianne Moore, begins to develop physical symptoms. These reactions, which range from coughing and vomiting to nose bleeds and seizures, take her from the doctor to the psychiatrist to, eventually, an igloo-like sanctuary in the arid desert. The exact source of these symptoms cannot be identified, and thus it seems to proliferate — if it can be anything, it can be everything — and the only thing anyone can find “medically wrong” with her is an allergy to milk, which she paradoxically drinks frequently and seemingly without issue.

Safe has been variously described as an allegory for the AIDS epidemic, an indictment of both patriarchal capitalism and self-help culture, and a warning about the environmental hazards wrought by the toxicity inherent in contemporary life. Viewed through today’s lens, it also brings to mind the growing awareness of so-called “invisible illnesses” and chronic pain. It’s not that Moore’s character can’t be believed, exactly, it’s that she can’t be diagnosed. She can achieve relief only through isolating herself more and more completely.

The same year that Safe was released, playwright Tracy Letts premiered a play called Bug. Ten years later, it was adapted for the screen by Letts and director William Friedkin. In movie form, Bug is a chamber piece that stars Ashley Judd and Michael Shannon as two strangers are thrown together by fate who become embroiled in a rapidly spiraling folie à deux. Insisting that the government performed tests on him while in the military, Peter (Shannon), easily convinces Agnes (Judd) that an infestation of “bugs” has been sent to surveil and torment him. Though it differs from Safe in a few marked ways, both movies portray a consuming need for purification and eradication.

Friedkin is, of course, most famous for helming The Exorcist, which with its focus on demonic possession and its gallons and gallons of “pea soup” is nothing if not an exercise in the abject. In other words, though The Exorcist is not often included in lists of body horror movies, it definitely qualifies. And Bug is, in its own way, about possession, in the form of obsession. Much like the events of The Exorcist might seem unbelievable to those not present in the room to witness them, Bug creates a dichotomy of “us vs. them” rather than the “me vs. my environment” trope that characterizes the conflict in Safe. While Safe is ultimately about isolation and surrender, Bug is about the need for confidants, corroborators, and co-conspirators.

Likewise, experimental documentarian Penny Lane’s newest offering, The Pain of Others, takes a look at the craving for connection that a controversial, self-diagnosed illness engenders.

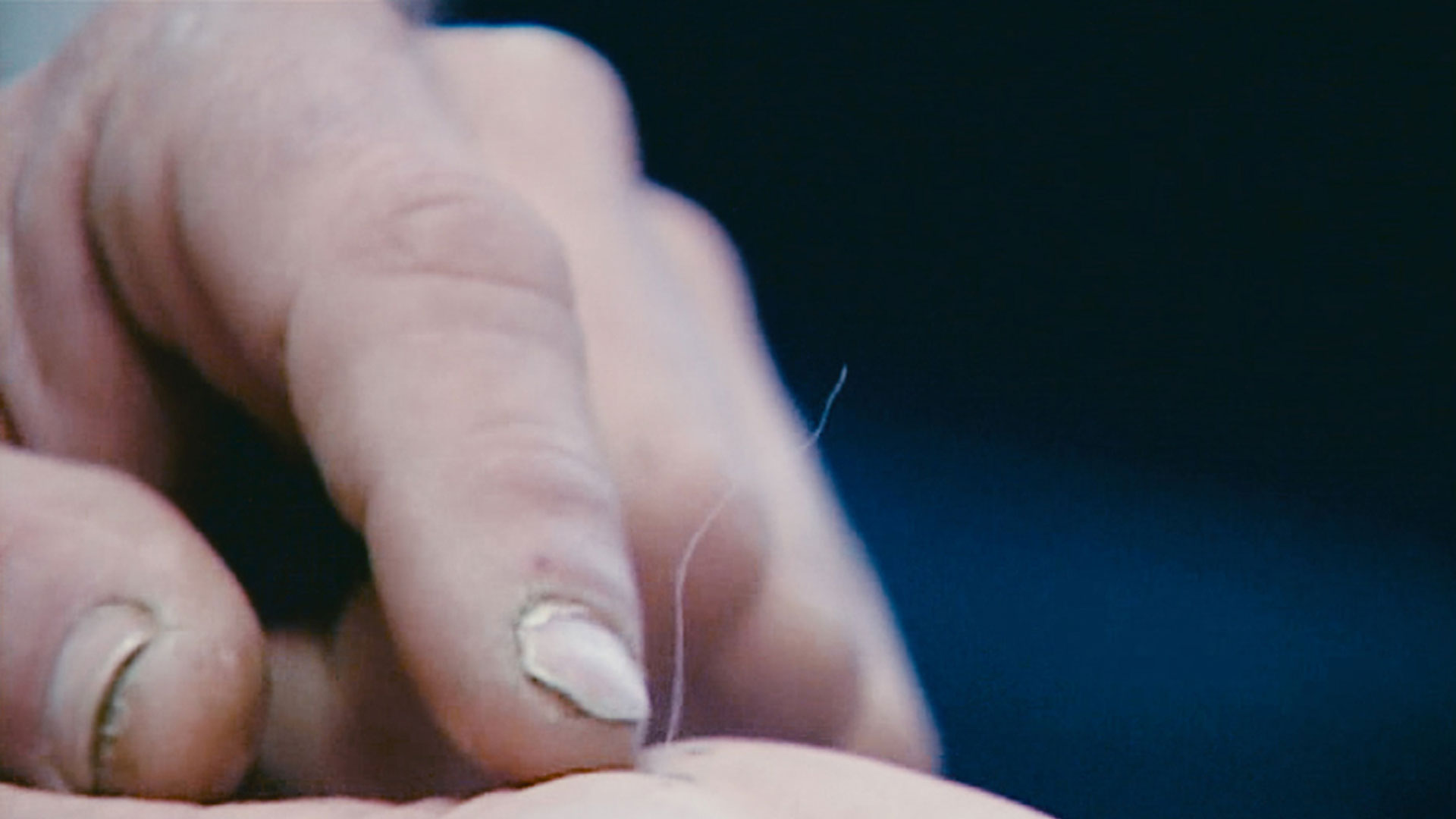

Morgellons disease is characterized by painful sores and the perception of “fibers” that extrude from them, and is not recognized by the mainstream medical establishment; nonetheless, there are many people who claim to suffer from it, who turn to platforms like YouTube to connect and share their stories. It is from this vast repository of documented yet controversial suffering that Lane built her movie, and while nonfiction, even creative nonfiction, might not often be thought of as a realm for body horror themes, she proves that experimental documentaries have something to contribute to the genre, especially in the “post-Internet age.”

While The Pain of Others might be one of the more uncomfortable movies to watch in the phantom body horror sub-genre, it is similar to both Safe and Bug through the absence of an observable cause for what is afflicting the characters in these films. The suffering is undeniable, but the reason for it… well, less so. Are the body horror home movies featured in The Pain of Others nothing more than a deluge of delusion? Are they the product of people so desperate to disassociate from their trauma that they externalize it? Or, are these the martyr-like canaries in the cultural coal mine, warning of a danger we’re otherwise blind to?

In conventional body horror films, the answer would be much more clear, and indeed central to the meaning of the story. But in these movies, ambiguity is the real threat. In that way, phantom body horror is a perfect trope for a “post-truth” cinematic landscape, in that it presents us with “post-truth” bodies. That they’re suffering is beyond or outside reason is beside the point.

Watch Now: If you’re “itching,” so to speak, for some phantom body horror, Penny Lane’s haunting found-footage documentary The Pain of Others is available for streaming exclusively on Fandor! And Bug, directed by William Friedkin, is also available on Fandor now through October 31, 2018.