Let’s begin by dispatching the inescapable bête noire. Let’s address “vulgar auteurism:” the term, the movement, the meme everybody loves to hate. If it’s somehow eluded you, here is a history in miniature. Andrew Tracy coined the idiom in an essay on Michael Mann in Cinema Scope in 2009: it was “one of the defining traits of latter-day cinephilia,” he wrote, a dire proclivity bristling with “tendentious interpretations” and “specious formalism.” The term was soon appropriated by genre film enthusiasts and writers who took seriously work that was widely considered trash. It became a shorthand for a certain kind of action movie: disreputable, low-budget, flamboyant, critically maligned. According to Wikipedia—and I swear I did not write this myself—vulgar auteurism “remained obscure until the publication of an article by Calum Marsh” in 2013. The piece was “immediately controversial,” apparently, and before long the term would be devoured by infamy. If it’s invoked now at all it’s only sardonically—a film critic’s inside joke.

Yes, well, this is all no doubt for the best. Vulgar auteurism enjoyed its moment of notoriety, launched briefly into the critical consciousness, and now it has receded from view as a bit of silly marginalia. But I wanted to bring it up here because I think it offers a useful illustration of the problems we face when talking about a director like Paul W.S. Anderson—a director who for one reason or another found himself at the very center of the V.A. discussion. As a critical perspective, a lens through which to look at and appreciate films, vulgar auteurism was unnecessary: no director is inherently unworthy of the “auteur” designation, which is to say that the ordinary brand of auteurism can accommodate vulgarity just fine. That was the central objection to the concept, if I recall the furor it aroused. But that wasn’t really the central idea. Vulgar auteurism wasn’t so much an approach to thinking about movies as a way to classify and categorize a particular kind of them. It was an appealingly vague term under whose aegis films and directors few respected could be legitimized and relished.

I suspect the idea emerged at least partly out of frustration. It was plain to see that Hollywood’s stalwart action directors—Tony Scott, John McTiernan, John Hyams, and, of course, Paul W.S. Anderson among them—were doing formally interesting and in some respects even audacious work in a field widely regarded as frivolous, and serious critics therefore scarcely took note. Broadsheet journalists would write about a film like Unstoppable or the direct-to-video Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning with thinly veiled disdain, paying scant attention to their formal aspects and instead ridiculing their flat acting or implausible stories. And what a tiresome habit that is. As ridiculous as vulgar auteurism could sometimes seem, at least it was attuned to film form and took movies like these on more reasonable terms. The tendency in mainstream criticism to lambast low-brow genre films for according with the generic convention—while simultaneously ignoring virtually everything else about them—makes it rather easy to sympathize with the counter-impulse of vulgar auteurism.

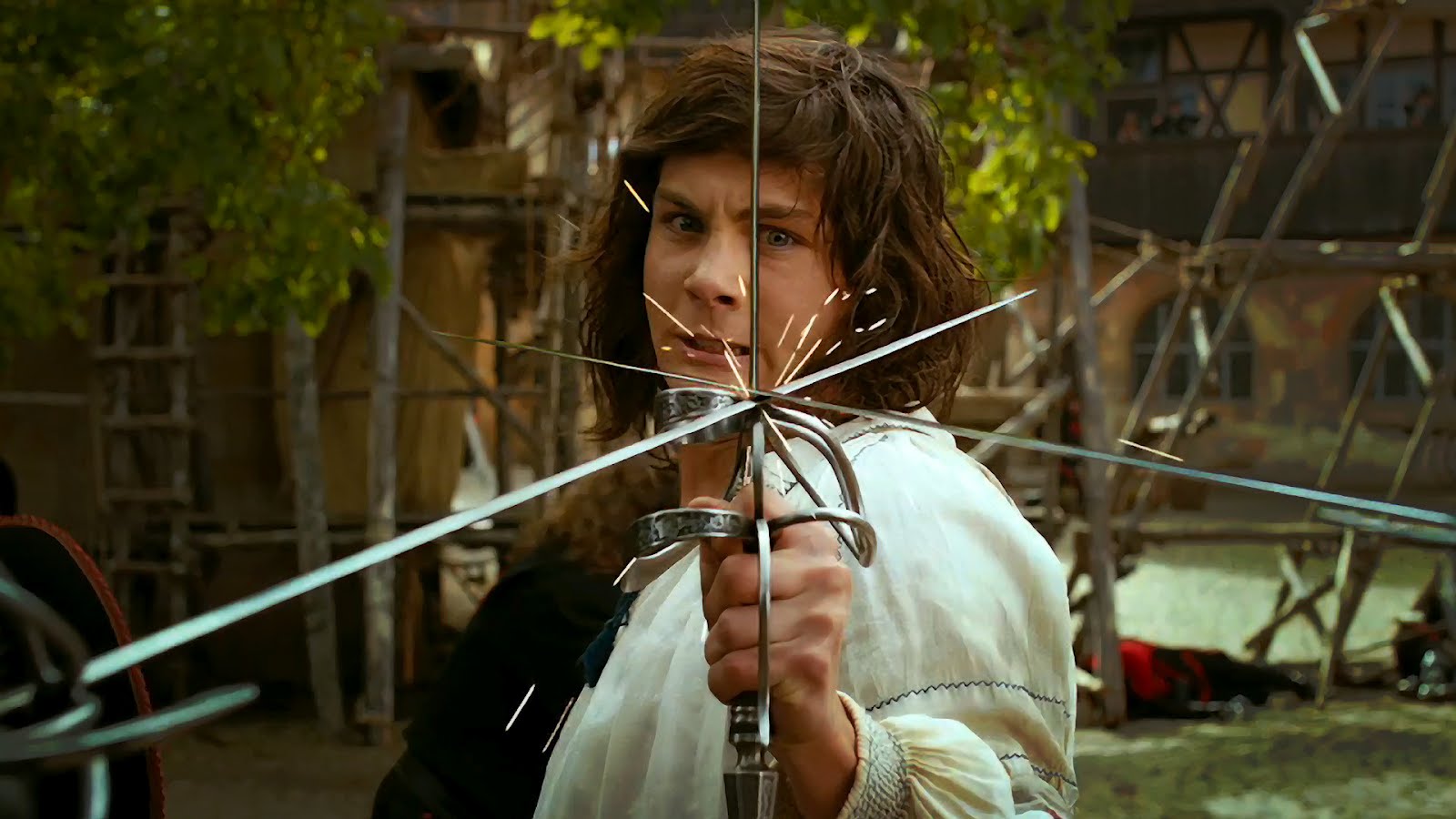

Paul W.S. Anderson is the ideal candidate for this sort of critical resuscitation. Anderson has directed eleven feature films over the last twenty years—and not one of them boasts a “fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Indeed, his best-reviewed movie to date, 2008’s Roger Corman remake Death Race, sits at a meager approval rating of forty-three percent, accompanied by this “Critics Consensus”: “Mindless, violent, and lightning-paced, Death Race is little more than an empty action romp.” For Anderson that qualifies as charitable. Most of his films hover around the twenty-five percent mark, with his lowest, 1998’s Blade Runner “sidequel” Soldier, clocking in at a paltry ten percent. Of AVP: Alien Vs. Predator (twenty-one percent), Rotten Tomatoes concludes: “Gore without scares and cardboard cut-out characters make this clash of the monsters a dull sit.” Of The Three Musketeers (twenty-four percent), my favorite of Anderson’s films, critics agree that it “offers nothing to recommend.” Critic Jeff Bayer, of some publication called The Scorecard, puts the consensus most succinctly: “Ugh.”

This is where the vulgar auteurists swoop in with a flourish to redeem Anderson’s exquisite cartoon epics. And so we get stuff like this, from a “critical discussion” of Anderson’s most recent film, Pompeii:

“Pompeii feels both alien and inevitable in his cinema. None of Anderson’s prior films are so deeply gestural as this; here he reduces romance to purely physical terms. Exchanges of glances, or the offering of a hand. Yet it feels entirely anticipated in his cinema. Resident Evil: Retribution and The Three Musketeers (2011) revel in bodies in motion, the grace of people within the director’s rigorous lines. Pompeii fittingly reduces this to the bare essentials, for his first romance…”

Well! Anyone allergic to things like “gestural” or (later in the same piece) “hyper-Sterbergian” ought generally to avoid this sort of praise, which responds to the philistinism of the Rotten Tomatoes crowd by charging headlong in the opposite direction. I’m not so sure I’d go so far as to call Anderson “more akin to John Ford or Roberto Rossellini than Josef von Sternberg or Fritz Lang, to whom some have compared him” (!), but I sympathize with the desire to regard the director of four video game adaptations this intensely and with this much conviction.

I like many of Paul W.S. Anderson’s films a great deal. But I do worry that talking about them in terms of his “deeply gestural” work or “rigorous lines,” or whatever other sub-academic abstraction feels vaguely appropriate, we are conceding that perhaps it’s more difficult to account for our tastes than we’d like. When somebody argues that, say, The Three Musketeers is vacuous and that its performances are poor, it’s difficult to articulate a defense that doesn’t merely contradict those opinions: it isn’t vacuous and its performances are quite good. And if nearly everybody seems to agree with the negative assessments, a compelling positive response may be harder to come by—unless one sidesteps those complaints altogether and offers positive evidence of one’s own. Hence, I think, the temptation to delve into a more idiosyncratic vernacular: when you start talking about the narrative as “so classical in trajectory that it goes beyond archetype,” which sounds like it means something important, the people who called it cliched start to look a bit daft. That fans of Anderson’s have taken it up as a line of defense is hardly surprising.

Which isn’t to suggest, mind you, that the hardcore vulgar auteurists are disingenuous—those responses are come upon naturally. With all of this in mind I returned recently to Shopping, Anderson’s once notorious debut. At first blush it seems more conventional, which is to say less irresistibly ludicrous, than many of the Anderson features that followed: unlike Mortal Kombat, his follow up, it isn’t based on a video game, and in fact has no fantasy or science-fiction elements at all. It’s a comic thriller with a story ripped from the headlines, as they say. Jude Law stars (in his first role) as a twentysomething “adrenaline junkie” obsessed with the art of ramriding—the apparently once-ubiquitous practice of driving a stolen car through the window of a shop before robbing it. The kids blow through the London suburbs ecstatic with their natural high, blasting early-nineties techno and looking for new stores to raid.

It’s pretty silly stuff, as you might expect, though Anderson stages and shoots the store-smashing sequences with admirable gusto. But the failures and merits of Shopping are apparent enough without recourse to any special critical perspective. You don’t need an analysis of visual space to see that Anderson has a keen eye for action and directs the film’s high-octane spectacles well. Nor do you need to furrow your brow to work around the film’s clumsy dramaturgy: all of that is clear. Anderson would go on to make more outrageous blockbusters, and over time he would hone his action-movie craft. But I wonder if perhaps the relative modesty of Shopping helps dispel the aura that has clung to Anderson since—the aura that makes some critics see his over-the-top lunacy as misunderstood genius while other critics merely cringe. Beneath that is a much simpler, if less glamorous truth: a director with a lot of talent who through no fault of his own has become both vaunted and maligned.