May 1, 1990. San Francisco, CA. Earthquake weather, unseasonably warm. Alt-country anti-hero Steve Earle is onstage at the storied South of Market nightclub Slim’s, two hours into an epic solo acoustic set. The self-professed hardcore troubadour has already slayed the capacity crowd with definitive renditions of a couple dozen of his finest songs, including “Angry Young Man” and “My Old Friend the Blues.” Earle is making a damn good case for himself as the neo-Americana genre’s preeminent practitioner. At least one audience member—dressed in faded Levi’s, thrift-store button-up, turquoise bolo tie and a pair of too-tight Durangos—is insisting to his buddy that no, he’s not crying, there’s just a little something in his eye.

Following yet another six-string stunner, Earle pauses, looks wistful, gently strums his guitar, and silences our applause with the slightest nod of his head. He’s got something important to tell us: “Townes Van Zandt is the best songwriter in the whole world, and I’ll stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say that.” Transplanted Texans and bespectacled collectors of out-of-print albums hoot and holler and raise their glasses aloft in beery cheer, their criminally neglected cult crooner at long last receiving recognition from tonight’s aces-high acolyte.

Earle’s fearless proclamation of Van Zandt’s greatness—c’mon, better than Dylan?—sent the teary twentysomething with tentative taste for torch and twang on a Townes tear. He heard “If I Needed You,” “Waitin’ Around to Die,” “Lungs” and the transcendent “To Live Is to Fly;” heard that voice, at once soft-spoken and stentorian; heard the words, both tender and self-lacerating. Could Earle be right?

Then everything went wrong. Earle disappeared from the scene for several years, caught up in heroin addiction and a stint in the slammer for weapons possession. Now drug-free, happily married for the seventh time, and justly proud of his gifted singer-songwriter son, the aptly named Justin Townes, Earle has lived to tell his own tale and also that of his idol, whose story has no such happy ending but whose remarkable music and reassuringly certain legacy live on in Margaret Brown’s elegiac yet unsparing 2004 documentary, Be Here to Love Me: A Film About Townes Van Zandt.

Earle figures prominently in the film, recounting the highs—both literal and drug-induced—of Van Zandt’s universally acclaimed though never commercially successful musical output, and the devastating lows of his increasingly hardscrabble country-outlaw lifestyle. Earle’s presence—along with that of reverential peers including Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, Joe Ely and Kris Kristofferson—also serves as a reminder of what might have been, if only Van Zandt had gotten clean, if only his records had been properly distributed, if only he hadn’t known far too well the particular loneliness of dingy motel rooms… But if so, would he still have written so many wise, gorgeous, grimly affirming songs?

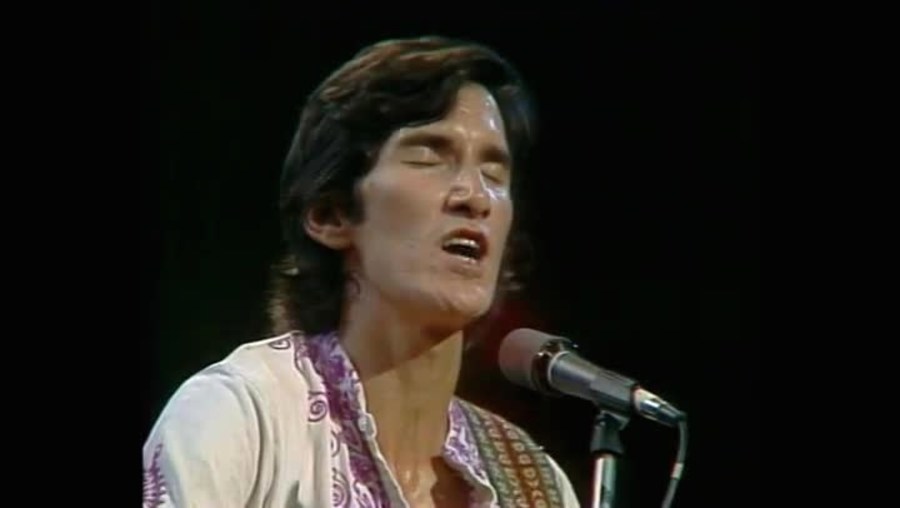

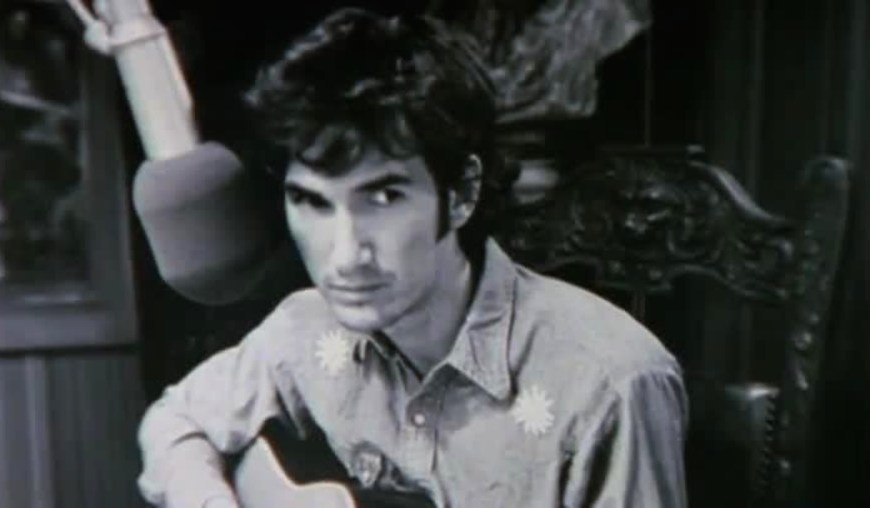

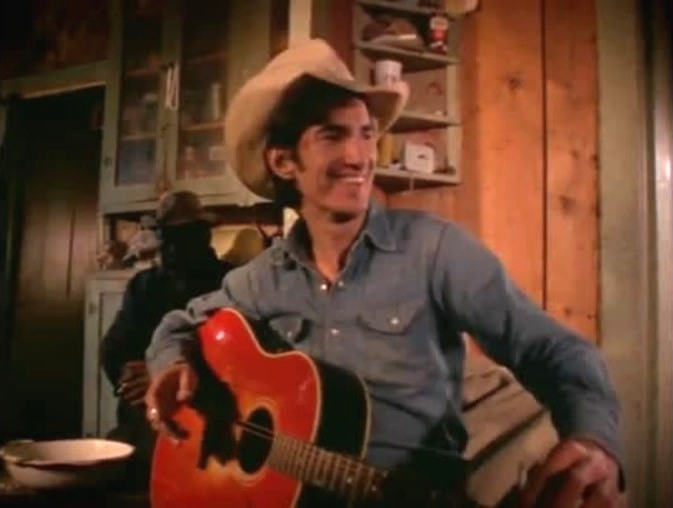

Brown’s melancholy film—lovingly assembled from archival footage, performance excerpts, and candid interviews with steadfast yet flummoxed friends, shady business associates, mourning family members and fellow musicians—subtly critiques the enduring allure of the suffering artist mythos that seemed to enchant Van Zandt, who time and again rushed headlong and heedlessly toward destruction. Through a stupefying concoction of minor chords and major chemicals, hard work and easy virtue, good looks and bad habits, Van Zandt—who died in 1997 at age fifty-two—willfully indulged the Thanatos instinct that led to the sort of clichéd country-music scenarios (a fall from a four-story balcony, shooting up in the presence of his eight-year-old son, hammering out his upper teeth, blithely taking swigs from a whisky bottle while toting a loaded shotgun) that he assiduously avoided in his own perfectly etched narratives (shorn of arrangements, his lyrics read like short stories akin to those of Raymond Carver and Thomas McGuane).

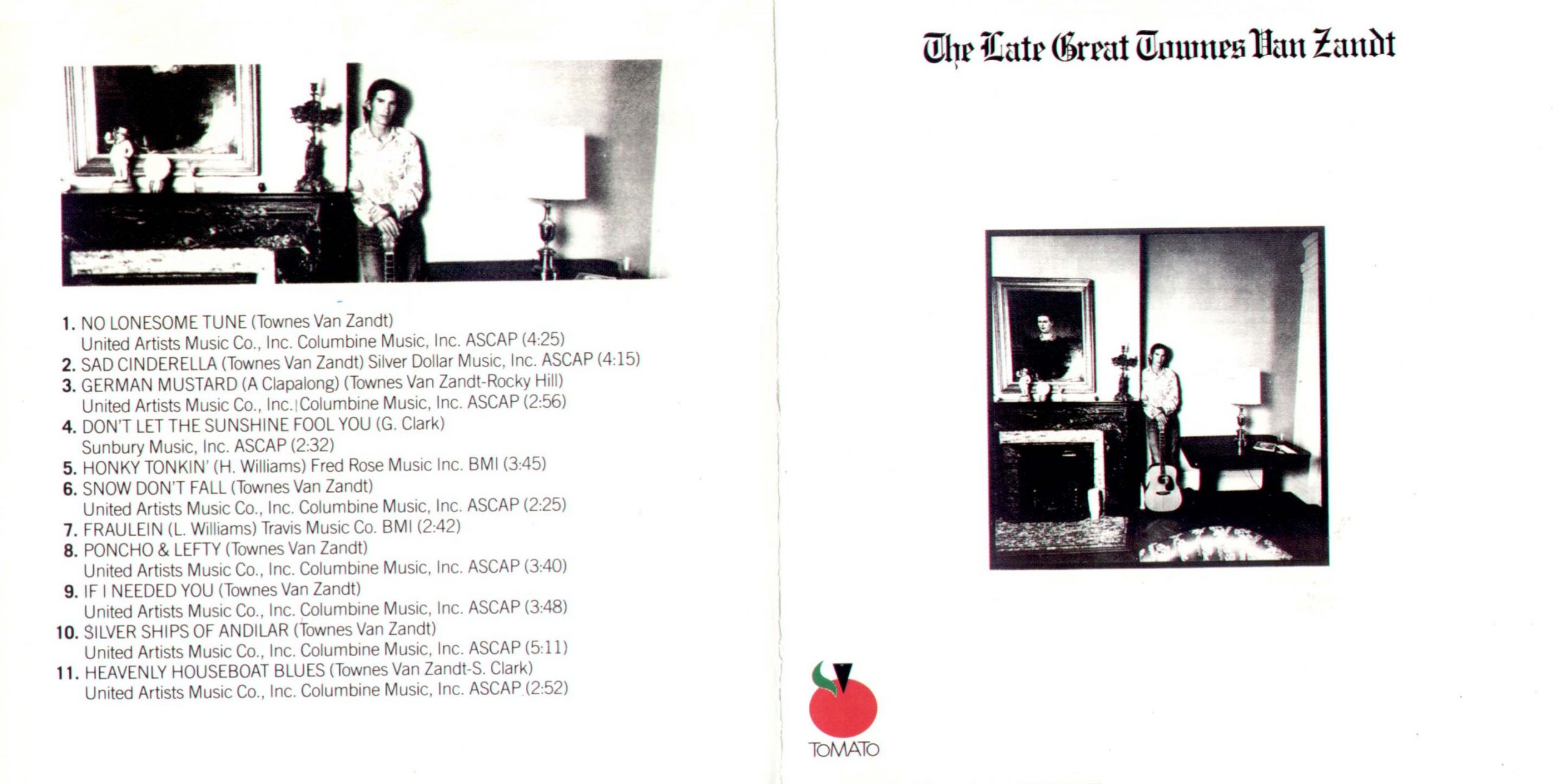

Van Zandt grew up comfortably upper-middle-class and was groomed for a career in red-state politics (I’m suddenly shuddering with revulsion picturing Bush senior and junior duetting on “Pancho and Lefty” in some hellish karaoke bar in Laredo or El Pico). Those plans were abandoned when he received an early diagnosis of manic depression and was subsequently treated with electroshock therapy, which erased big chunks of his long-term memory. Hooked (or “stuck,” as he liked to joke) on airplane glue as a high schooler, Van Zandt soon graduated to stronger stuff. Neurotic on weed, psychotic on booze and known to inject a what-the-hell combo of bourbon and Coca Cola, Van Zandt claimed to have once been declared DOA for a full ninety minutes before a doctor pummeled him in the stomach and brought him “back to this joyous earth,” as he recounted with ironic relish. Was it with the same irony or perhaps eerie prescience that he titled his 1972 album The Late Great Townes Van Zandt?

Misadventures in pharmaceuticals notwithstanding, Van Zandt remained suitably lucid to write, record and perform one great song after another, much to the amazement of his small but devoted following. Initially influenced by the work of blues great Lightnin’ Hopkins and tousle-haired folkie Dylan (he of the aforementioned coffee table), Van Zandt soon established his own inimitable approach to crafting somber character studies set to haunting melodies that left plenty of room for vocal resonance and moral ambiguity. Kindred spirit Guy Clark, who playfully chastises his much-missed pal for being a “kinky motherfucker” and unapologetically flirting with Clark’s wife, recalls Van Zandt’s peerless ability to casually debut “songs that just took your breath away.”

Three wives, three kids, critical accolades, scant sales, broken bones, broken promises…and decades without stepping foot in a grocery store (Van Zandt did all his shopping at the 7-11 around the corner). Until the end, he was, if not quite handsome, then certainly striking, resembling at various stages Sam Shepard (the intellectual cowboy), Sam Waterston (lawless and disorderly) and Harry Dean Stanton (roaming the desert in Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas).

Fittingly, Brown shares Wenders’ love of the wide open spaces of America’s topography, both geographic and emotional. She shoots the passing terrain through rain-streaked car windows, the details of the landscape lost amid impressionistic blurs—a visual corollary to Van Zandt’s descent. (Cinematographer Lee Daniel, who worked with Richard Linklater on Slacker and Dazed and Confused, does excellent work here.)

Brown’s graceful stylistics and finely honed storytelling skills are evident throughout Be Here to Love Me as well as in The Order of Myths, her 2008 doc about the racially divided annual Mardi Gras celebration in Mobile, Alabama; and in her most recent work, The Great Invisible, a study of the vicious and viscous aftermath of the 2010 BP oil spill, which won the 2014 SXSW Grand Jury Prize for Documentary.

As for Van Zandt, his music is now far more widely appreciated than during his own tumultuous lifetime. Earle released the covers album Townes in 2009, and Van Zandt originals have added gravitas to Crazy Heart, In Bruges, Seven Psychopaths, Deadwood, True Detective and Breaking Bad (with Walter White and Jesse Pinkman as Pancho and Lefty). His killer version of the Rolling Stones’ “Dead Flowers” serenades the final scene of The Big Lebowski. The Dude abides, indeed.

Sometime before crossing over into the wild blue yonder, Van Zandt got word of Earle’s oft-quoted declaration, and deflected his admirer’s hagiographic claim with customary nonchalance: “I’ve met Bob Dylan and his bodyguards, and I don’t think Steve could get anywhere near his coffee table.”