[Editor’s note: This feature marks the sixth piece in an Orson Welles series celebrating the 100th anniversary of the filmmaker’s birth, which is today. See previously published pieces: “Orson Welles: The Enigmatic Independent, “The Orson Welles Bookshelf,” “Rosenbaum on Welles at 100” and “Schooled by Orson Welles: Roberto Perpignani,” “Orson Welles Goes Around the World” and others in the Keyframe archives.]

“[I]t’s my own picture, unspoiled in the cutting or anything else…. The producers were heroic and got it made, and there isn’t anything I had to compromise—except no sets, and I was happy with the other solution, as it turned out, even though I was kind of in love with all the work I’d done. Still, I was happy enough to scuttle it, as I always am.”

–Orson Welles on The Trial, from This is Orson Welles

Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1959) is now celebrated as a masterpiece, but the version released in 1959 was not the film that Welles had intended and it was largely dismissed as a glorified B-movie. It had been for Welles one last attempt to make films inside the studio system and he brought the film in on time and on budget. Yet Universal thought that his labyrinthine nightmare of a crime movie was too dark and confusing for audiences and took the editing from his hands. Welles’ famous fifty-eight-page memo (which became the basis of a 1998 revision undertaken by producer Rick Schmidlin and editor Walter Murch) was politic, polite and even supportive of some of the changes made by Universal’s editor as it made the case for editing refinements. Welles played by the rules right to the end, attempting to work with the producers rather than fight them, but it became clear that Hollywood simply did not want the kinds of films that Welles made and he left for Europe. Never again did he work with the budgets or the resources of a major studio production. That was his trade-off for creative control.

The Trial (1963) was not Welles’ first project after Touch of Evil—he started shooting Don Quixote in Mexico and Spain and made a series of documentaries for Spanish TV—but it was the first film he completed after leaving Hollywood. Michael and Alexander Salkind, a father and son producer team, offered Welles his choice of literary adaptations from a list of public domain properties (Franz Kafka‘s The Trial was on the list but not in the public domain after all and they had to purchase the rights) and promised him creative freedom. It was not an obvious project for Welles. He favored films about the great and/or powerful men who fall and stories of corruption and abuse of power, but he never wrote a character who gave in or gave up. So while Welles’ adaptation is remarkably faithful to Kafka’s text, he nonetheless puts his sensibility on the story. Joseph K. may not beat the system, but neither does he resign himself to it.

It was financed internationally so Welles gave it an international cast, the better to blur the specificity of the setting. Anthony Perkins was his first choice for Joseph K., the otherwise anonymous white collar worker arrested for an unidentified crime. He provided the film with a recognizable star and his boyish modesty and nervous indignation gives K an attractive everyman quality. The supporting cast came from France (Jeanne Moreau, Suzanne Flon, Michael Lonsdale), Germany (Romy Schneider), Italy (Elsa Martinelli), Switzerland (Max Haufler) and elsewhere (Russian-born Akim Tamiroff, a Welles regular) and Welles himself took the role of the Advocate, wielding the law like a switch to intimidate and dominate. Originally he was to play the Priest but when his first choice for the Advocate, Jackie Gleason (fresh off The Hustler) turned down his offer, he stepped in to provide the necessary stature.

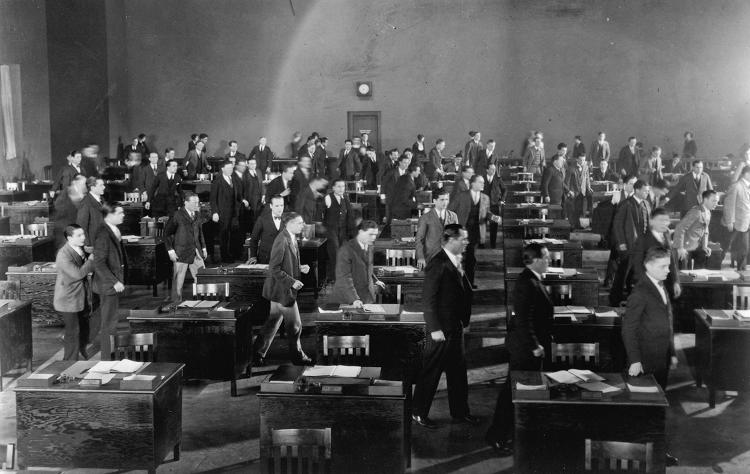

The Salkinds wanted to shoot predominantly in what was then Yugoslavia (now Croatia), where production costs cheaper, with additional studio scenes in Paris. Welles scouted locations around Zagreb, where he found a block of post-war block apartments in a rather despairing location that suited his vision of Kafka’s alienated world. That style of Soviet architecture sets a particular sensibility of impersonal efficiency and drab modernism, both new and neglected at the same time, and Welles adds to the isolation by shooting Perkins on a landscape bereft of human activity. It also associates Kafka’s nightmarish world of oppression through intimidation, bureaucratic indifference and official obfuscation with modern Soviet culture. Kafka’s 20th-century nightmare echoes through the “socialist ideal” behind the Iron Curtain. Other, pre-Soviet Zagreb buildings provided unreal locations for Joseph’s odyssey: the cavernous office packed with desks and typewriters laid out in conformist rows (recalling both The Crowd and The Apartment), the grand opera house, the mammoth exterior of the church and the deserted city streets.

This was not Othello, where Welles had to suspend shooting to go in search of completion funds, but there were financial problems nonetheless. When promised funds failed to materialize, the Zagreb shoot was cut short and Welles and his cast and crew returned to Paris to complete the film. On Othello, Welles worked around the challenges of a peripatetic production, which he shot piecemeal over locations spread across multiple countries and separated by months and even years, by matching shots through careful framing and creative location scouting and by meeting adversity with ingenuity. For The Trial picked up exteriors in Paris, Milan and Dubrovnik and built the labyrinthine world of K’s odyssey in the Gare d’Orsay, the massive abandoned Paris train station that was later used by Bertolucci in The Conformist and ultimately reclaimed as the famous Musée d’Orsay. Welles had designed elaborate sets to be built in the studio but he threw them out and started again from scratch, taking inspiration from the opportunities offered by the space and even the detritus left behind, from tables and chairs to bundles of abandoned paper records. The vaulted ceiling gave him the cavernous rooms of the Advocate’s house. The overhead scaffolding and catwalks take K deeper into the hidden bowels of the impenetrable government. The portrait painter’s surreal garret, a cage-like shack of haphazard slats, is suspended in some impossible location and connected to the courts by dizzying staircases and surreal tunnels.

The legal system is a literal maze in Welles’ visualization and the disparate locations all lead back to one another. The Trial favors long takes and sustained shots to the fractured editing that defines so much of both the European Othello and the American Touch of Evil, but as we leaves Joseph’s familiar world and follow him through the surreal legal labyrinth, the editing becomes faster and more fragmented. The logistics of space is distorted and exaggerated by the editing to show the perverse conspiratorial integration of the incestuous system. Shots between locations, and even within the same scene, are cut together from diverse sources and Welles doesn’t match them so much as connect them, using action and momentum and graphic cues to carry us through the incongruities.

Welles use of young and unknown editors and cameramen was not a matter of economy but control. Having been betrayed too often by editors beholden to the producers, he brought in his own crew of largely novice cutters and oversaw the entire process with detailed instructions. His cinematographer, Edmond Richard, had never shot a feature film before, but his background in camera design, special effects and lab work gave Welles an expertise he could tap. Welles framed his own shots and planned his elaborate camera movements. He needed someone to execute those images within the restrictions of his budget, equipment and shooting schedule. Richard worked quickly and gave Welles images that pushed the black-and-white contrast to unnatural extremes.

Finally, there is the highly stylized soundtrack. You don’t need to be a Welles aficionado to hear his voice throughout the film. He dubs almost every male actor in the film, eleven characters by his own count, even those that speak perfect English. (The exceptions are Perkins, of course, the distinctive Akim Tamiroff and Jess Hahn, one of the two policeman who first confront Joseph). It gives the film an added layer of unreality and Welles an added dimension of control. French Welles historians Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas suggest that it also ties all those characters together as an entity and subtly adds to the paranoid atmosphere.

Orson Welles is the total filmmaker on The Trial. He applied the lessons learned on Othello and Mr. Arkadin to a more controlled situation, shaping every aspect of the film, planning elaborate shots where he could, improvising to make use of opportunities where they presented themselves, embracing change and incorporating it into his vision with the support of his cast, crew and producers. It was antithetical to the Hollywood model, where everything was planned out and departments took charge of their piece of the production, but it was the way he worked in the theater and on radio and it was the atmosphere within which he was most creative. Perhaps that’s why he proclaimed to Peter Bogdanovich that The Trial was “the most autobiographical movie that I’ve ever made, the only one that’s really close to me.”