Each year’s Oscar lineup for Best Picture leaves a bitter taste in my mouth. Invariably, I find myself dissatisfied with the films chosen by the Academy. While this year’s lineup was improved by films like Lady Bird and Get Out, the other movies chosen to be nominated were disappointingly safe. Call Me By Your Name, by Italian director Luca Guadagnino, which charts the summer-long relationship between 17-year-old Elio (Timothée Chalamet) and graduate student Oliver (Armie Hammer), may seem like another example of a movie operating outside of mainstream cinema finally getting the attention it deserves from the Academy. But, more significantly, it strikes me as an indication of the flawed populism of the Academy, as well as Guadagnino’s insecure pacification of André Aciman’s novel.

Cards on the table, I did take issue with the film prior to its nominations (and subsequent win for Best Adapted Screenplay). I attribute my underwhelmed emotional reaction to the film’s white-male-privilege, bourgeois narrative, and its academia-influenced emotional detachment. That detachment, which acts as a bulwark towards real conflict, and the privilege, which when paired with Guadagnino’s intense focus on surfaces (statues, monuments, bodies), never manages to give way to the interiority of the characters, and left me feeling apathetic — even if the movie is well-crafted. Guadagnino sacrifices vitality for the aesthetic of grandiloquence. See the locale of the Italian idyll, which allows for beautiful shots, but infects the film with sleepiness that mutes the passion and raw desire that first loves should inspire; or see Marzia’s (Esther Garrel) character arc: Elio promises not to let their sexual escapade turn into a one-night stand, and then promptly does. She is then written out of the film almost entirely, save for one last scene near the end in which Elio is absolved by a sincere apology from her that wraps a neat bow on the film. Can you say wish fulfillment?

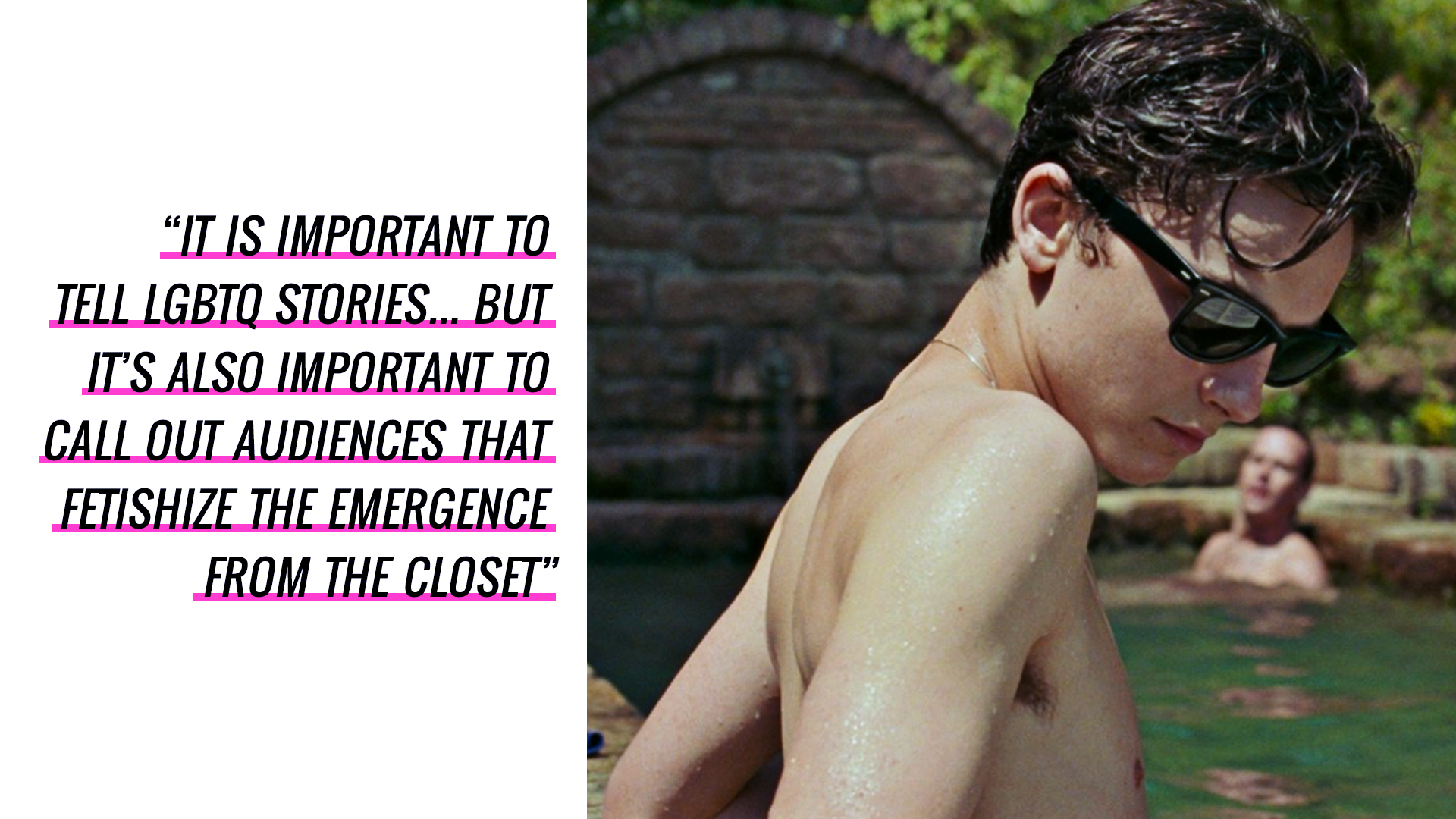

Apart of me wants badly to respect the conflictless nature of the narrative, which contrasts a heteronormative mindset that suggests any romance that isn’t between a man and a woman is somehow “irregular.” But here, the progressiveness feels suppressed by the characters’ wealth and power. Elio is left unscandalized, the film insinuates, because he lives in a community of rich, pompous intellectuals. In contrast, this pristine representation of their community is the ignominious way Guadagnino characterizes the difference between Hammer’s Herculean figure and Chalamet’s boyish body. The age gap between the two — Oliver is 24, Elio is 17 — is not entirely unethical, but I still find the paedophilic quality of the voyeuristic lens unshakably alarming.

The shallow emphasis on wealth and aesthetics extend to the slightness of Elio’s struggle with his sexuality — that sense of need that comes with the suggested “amour fou” — and never resonates outside of the now-famous peach sequence. And even that resolves anti-climactically, as the camera pans from the two lovers to a tree outside the window.

Guadagnino’s justification for the censorship of this sex scene—that the audience’s gaze on the act of sex would be an “unkind intrusion” — is apt. But placing the exaltation of this film in the context of some of the bolder (and better, in this writer’s opinion) LGBTQ stories told this year, such as Robin Campillo’s BPM, Alain Guiraudie’s Staying Vertical, and Olivier Ducastel & Jacques Martineau’s Paris 05:59: Théo and Hugo reveal a greater, more systemic problem exemplified by the chasteness of Call Me By Your Name: The film follows a pattern of gay tokenism which bestows critical acclaim, wide viewership, and Oscar buzz on films that manage not to offend mainstream sensibilities. It’s not that the film isn’t progressive, but rather that it isn’t doing anything new. Instead, it falls into the trappings of earlier iterations of queer cinema that exploit queer pain.

It is important to tell LGBTQ stories — especially ones that do not resort to absolute dramatics — but it is also important to call out audiences that fetishize the emergence from the closet yet remain unwilling to recognize the other unique cultural and social aspects of the experience. Rather than essentializing the “closeted gay” trope as mainstream culture seems to want to do, filmmakers should instead be celebrating the entire narrative, even if it may cause some initial discomfort.