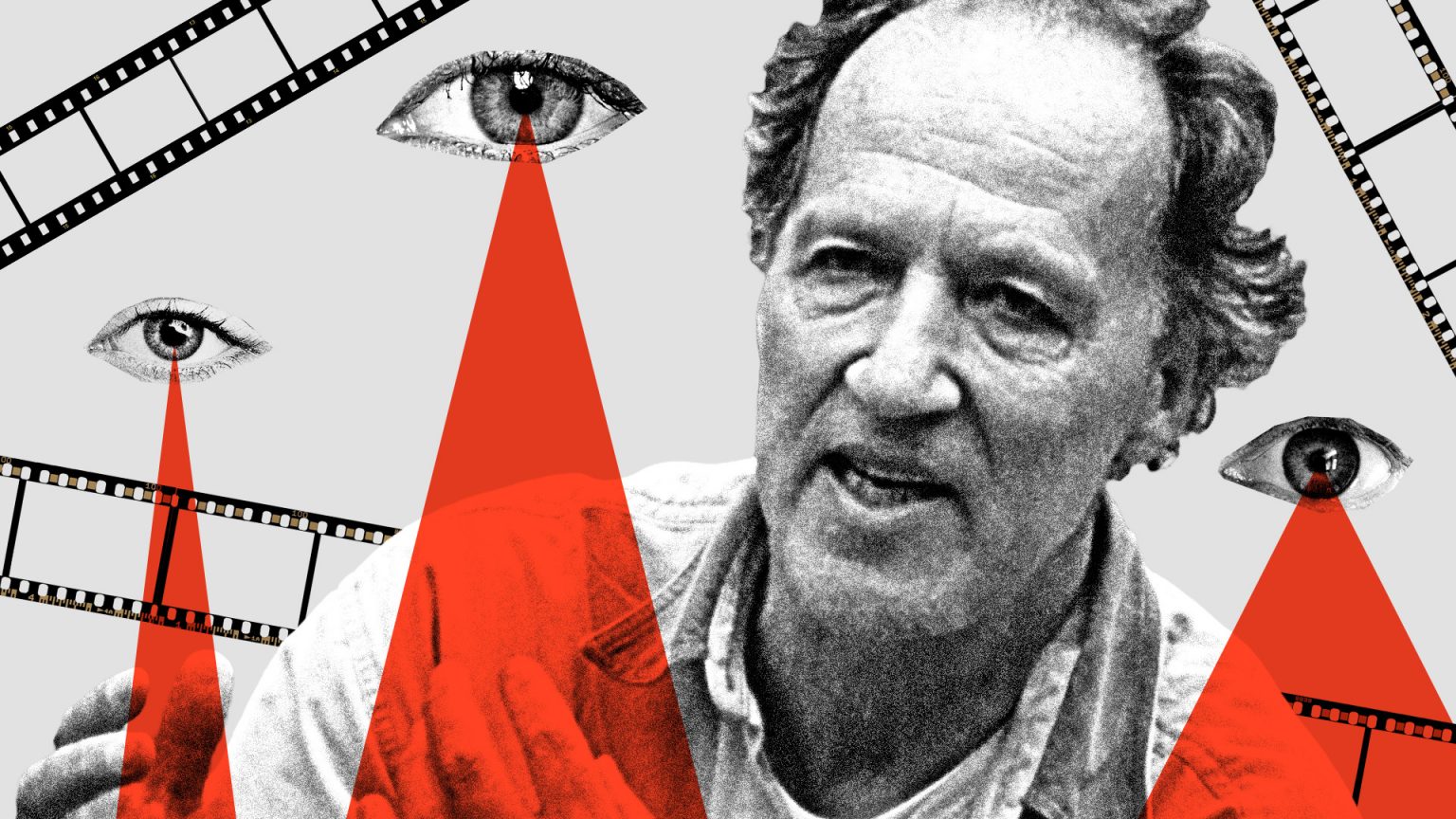

In 1999, Werner Herzog spoke at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. He took the stage and read from a prepared statement. This statement, which he calls the Minnesota Declaration (which should tell you that even when serious, Herzog’s tongue is planted firmly in cheek), outlined the director’s views on the role of truth and facts in documentaries. If it’s not immediately obvious why a conversation on truth vs. facts is absolutely necessary, I welcome you to open any newspaper and skip to the “Politics” section. In fact, Herzog wrote a six-point addendum to the piece in June of 2017, specifically targeted at this new age wherein we seem to have found the melting point of fact.

So what does any of this mean? Well, in a nutshell, Herzog says that Truth and Facts are both important, both nourishing — but they provide two different kinds of nourishment; In Herzog’s own words, “Facts create norms, and truth illumination.” But again, what does that mean?

Facts can be considered, to borrow Herzog’s word, a “norm” on which we, as in humanity, either consciously or unconsciously, agree to, and through which we collectively understand reality (as much as is possible). Okay, stick with me on this: Metaphysically speaking, if we pick up a stone, show it to someone, and ask, “What is this?” they will, almost invariably respond, “a stone.” Why? Maybe because it’s hard, or gray, or rough to the touch, or because when we throw it, it skips neatly across the surface of a lake or makes a very satisfying “glunk” sound as it sinks; it resembles countless other stones we have seen and examined over the courses of our lives. To put it succinctly: We can agree that this thing in our hands is a stone because it possesses “stone-ness,” or in other words, it possesses the essence of a stone. If a person responds with any other answer than “a stone,” they lose their credibility, because, after all, we all agree this thing is a stone. And we can take that same approach to documentary films: If a film zooms in on a stone and says, “This is a chair,” well, it would sort of make us doubt everything else in the movie, right? I mean, unless it did it in an exceedingly poetic way — but more on that in a moment.

The problem we run into on a day-to-day basis is that those in power are more than happy to call a stone a chair and think that if they repeat it enough that we’ll start to believe it.

And many people have.

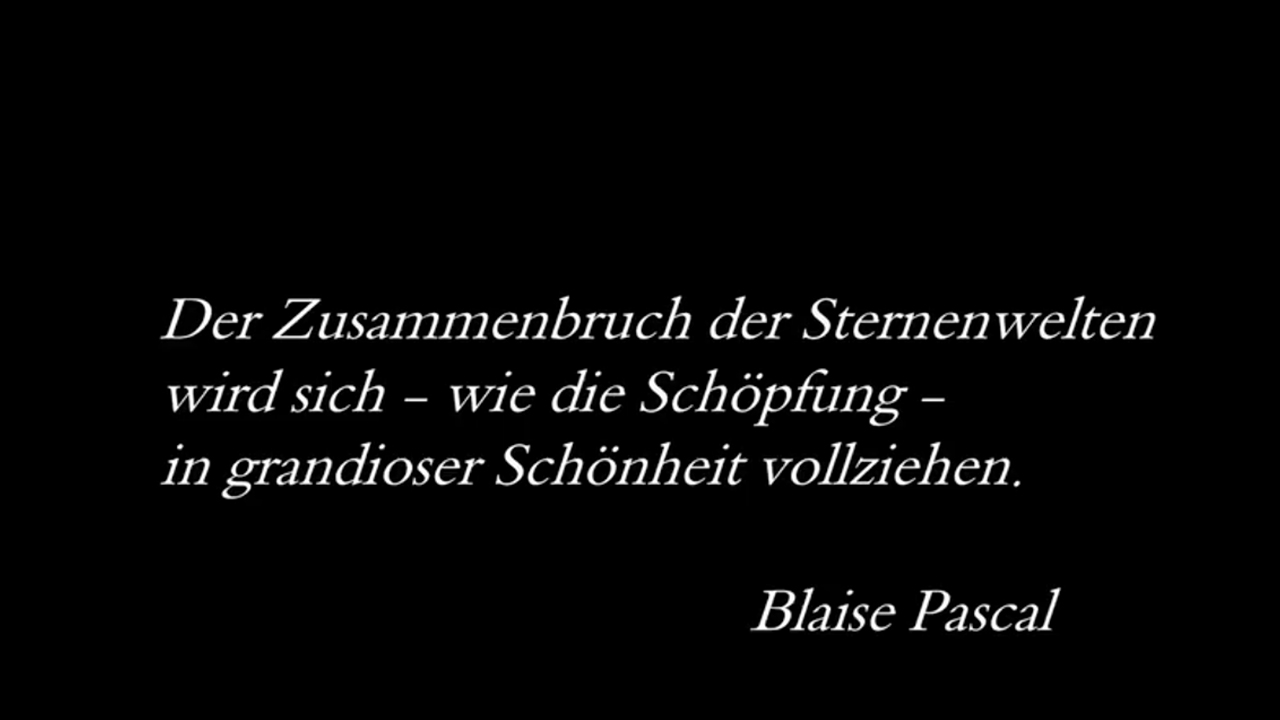

Truth is a different thing altogether. A politician should have a commitment to the fact, but the truth is all about perspective and belief. They should not bend facts to support their personal truth, or worse, to mislead people. But a filmmaker, even a documentarian, might play with fact in order to achieve truth. Here’s an example from Herzog’s film Lessons of Darkness:

Here’s the issue: Pascal never wrote or said that. It’s a Herzog original. But does knowing so make the sentiment any less truthful? Herzog argues that it does not, and I’m inclined to agree. Especially when the black card gives way to the scorched earth and fire of the oil fields of Kuwait. We’re at the beginning, but it feels like the end.

As Herzog says, “There are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.”

So how does this bending of fact differ from what Donald Trump and other politicians engage in? Or, even more directly, how does what Herzog makes differ from documentaries by Dinesh D’Souza or even Steve Bannon?

It differs because Herzog’s goal is to reveal some ecstatic truth about humanity — movies like Grizzly Man probe into a person’s relationship with nature; Into the Inferno and Encounters at the End of the World show the breadth and power of our natural world and our smallness in comparison; Cave of Forgotten Dreams returns us to the womb for the birth of art, and, not-coincidentally, humanity; Into the Abyss finds that humanity again, even in conversations with killers. All of these films search for and reveal truths, big and small; watching them, you get the feeling that something inside you is changing according to the film.

But politicians like Trump and filmmakers like D’Souza (who’s popular among the same people who go to Breitbart and InfoWars for their news) conflate truth and fact. Meaning, they present personal truth, sometimes in the form of meme-able sound bites along the lines of “Crooked Hillary” and “Make America Great Again,” as fact. There are no revelations to be found here, just grade-A spin that’s about as subtle as a hammer. But say it enough, and it begins to sound like the truth.

As Herzog says in his addendum to the Minnesota Declaration: “The argument of rearranging facts constituting a lie points only to shallow thinking and the fetish of self-reference.”

So what is the place of the documentarian in this brave new, post-truth, alternative-fact-driven world? Is it to present fact as rigid steel? There are plenty of amazing documentaries that operate on that level and reveal truth simply by supplying facts heretofore unknown to most of the audience. Documentaries like last year’s Oscar-nominated Last Men in Aleppo, Strong Island, and Abacus: Small Enough to Jail all achieve a level of grace through the facts they reveal in telling their stories. But the kind of documentaries that Herzog makes, the kind that, like Lessons of Darkness, openly present you with evidence of its own bending of facts to ready you for the ecstatic truth it strives for, is just as important.

Again, as Herzog says best: “Facts cannot be underestimated as they have normative power. But they do not give us insight into the truth, or the illumination of poetry. Yes, accepted, the phone directory of Manhattan contains four million entries, all of them factually verifiable. But do we know why Jonathan Smith, correctly listed, cries into his pillow every night?”

It’s documentaries like Herzog’s that might answer, “Why?” That is their power. That is why they are necessary. So today, I’d like to thank Werner Herzog. His movies have changed my life for the better; he’s helped me understand things I didn’t know I misunderstood and led me to answers I didn’t know I was seeking. Today, more than ever, we need people like him and movies like that.

Watch Now: Lessons of Darkness and many of Werner Herzog’s other films right here on Fandor.