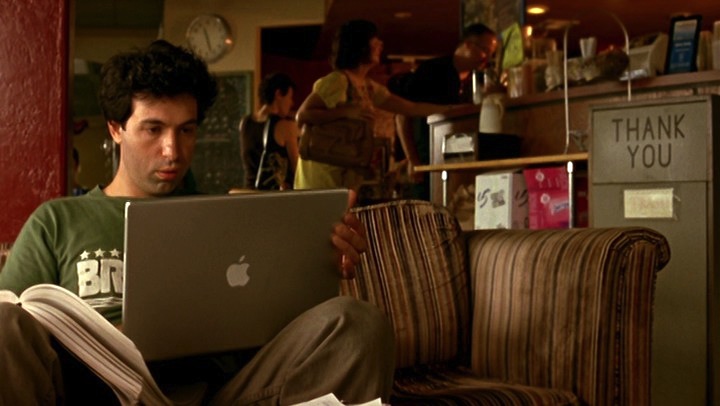

There’s a certain kind of independent film director who is destined, or cursed, to be venerated maybe five, or fifteen years down the line by diligent curators who’ve enjoy his modest, casually insightful works. Usually it takes at least a few retrospectives to make his (or her) name, then he might go on making similarly solid films, for a similarly stalwart audience, until he no longer deigns to do so. Simultaneously more easily misunderstood than similarly hard-working contemporaries like Joe Swanberg and less flashy than more ‘intellectual’ perfectionists like Shane Carruth, Alex Karpovsky could be this kind of director.

Unlike Swanberg, whose Olivia Wilde-starring Drinking Buddies will come out this fall in wide release, Karpovsky’s four narratives (and one documentary) would never make sense in a multiplex—unpacking the hopes and fears of a character audiences might not always like isn’t an affair to be conducted in a large auditorium. Their common fascination with jerks, failed relationships and his own ‘death anxiety’ seems uniquely tailored to a more intimate stage. It seems to makes sense that he’s found the greatest acclaim on the small screen, as a particularly unflattering version of himself, the all-too-relatable misfit Ray on HBO’s Girls.

So relatable, apparently, that publications far and wide are writing editorials on how cute his hair is or what a big crush they have on him—hyperbole Karpovsky himself would probably agree wouldn’t be conferred on another, similarly genetically blessed man. The Woody Allen comparisons haven’t hurt either. His stock in New York is high enough that his new films Red Flag and Rubberneck, which he made back-to-back for an absurdly low amount of money, received prestigious Lincoln Center screening simultaneous with their VOD release.

It says something interesting about Karpovsky, and about the times we live in that anyone remotely compared to Allen could be more famous for his acting than his other, admittedly accomplished, work. The picture becomes clearer upon inspecting his filmography, which pegs his current number of roles as an actor at a whopping twenty six since his first role in Andrew Bujalski’s Beeswax only six years ago. The well-earned understanding and that makes him stand out as an actor also underpins the success of his films: that’s why people watching them now instead of ten years down the line, and what a relief. In anticipation of seeing Karpovsky, and Red Flag, in a spotlight program at the San Francisco’s Jewish Film Festival this weekend, we spoke to the actor/director/writer about work,

Keyframe: I was looking at your website and realizing you’ve done almost fifty interviews in the last three months. You must be tired.

Alex Karpovsky: I have a very talented publicist. When you don’t have sort of a P & A budget, the only way to get word out is by doing interviews.

Keyframe: Considering the scale of your own films, I’m sure it’s been a big help.

Karpovsky: Very much.

Keyframe: If I can call on a distant memory, I was hoping I could take you back to [Andrew Bujalski’s] Beeswax, which was the first time I noticed you as an actor. I’d been a fan of Bujalski’s since he did Funny Ha Ha, which seems to me to have been an unbelievably long time ago at this point. While I don’t want to use a silly phrase like ‘godfather,’ he’s in some ways a forebear of the kind of projects you’ve worked on, from Girls to your own films. What was making Beeswax like for you?

Karpovsky: It was six ago this month that we shot the movie, 2007. I didn’t ever really think I was going to be an actor; it was never something that I aspired to or that my daydreams wandered towards. I wanted to be a writer/director, or an editor—I was content with one of those behind-the-camera positions. I did put myself in my first movie, but that was somewhat out of necessity in the sense that I didn’t go to film school, I didn’t do any short films, I just kind of cannonballed into the feature film film pool. I knew I’d make a lot of mistakes, and I certainly did. I knew it would take a lot of time because of that and it certainly did. I put myself in my first movie just because I felt that I couldn’t rely on anyone to be around for two years and not change their haircut and all the rest of it.

So I made my first movie then I started with my second and I was editing my second movie when Andrew asked me to come on board for Beeswax. But I wasn’t in my second movie, nor was I in my third movie, which I started making a few years later: I’m really being honest when I say I didn’t have any intention of being an actor. But for whatever reason, Andrew saw me in my first movie The Hole Story and wanted me to be in Beeswax, and that was the first time I had to act in anything that wasn’t my own. If it wasn’t for him, I would never have any acting future. I’m pretty confident in saying there would be no way. It took two years for Beeswax to come out, and in the interim I wasn’t asked to act in anything else. So I know for certain that I would have never acted in anything else ever again.

There’s that and, on a different note, watching the director work, a director who’s so focused on the character, and the performance and the dynamics and the relationships and the personal chemistry—all that stuff that drives him much more than the technical and aesthetic aspects sometimes—that was really great, because those are my interests as well. To see him communicate with actors and express a sensibility that’s so clear but yet he’s able to share it in a way that’s really accessible. All that was an extension of my film school which was really great. He continues to be one of my favorite filmmakers and is probably the nicest guy making movies that I know of. Just a very genuine, sincere, honest person.

Keyframe: He comes across that way in interviews. [See ‘Bujalski Then and Now‘ interviews on Keyframe.] There’s something about the way he uses character that you’re so well suited for. There’s a line in Beeswax that seems really pertinent to the internal tension in the characters you create where you say, ‘In my mind it sounded so different than the way it came out. It sounded hilarious. But it came out so not hilarious.’ There’s a funny way that’s played out in your career—it’s the whole crux of Rubberneck for example.

Karpovsky: I’m definitely interested in character -driven stories, and one of the things that I think drives character-driven stories is internal conflict. Sometimes for dramatic visual effect and sometimes for comedic effect but yeah there’s definitely an internal war going on and we’re only getting the reverberations that get to the surface. That’s also true in Red Flag as well. [My character is] sort of negotiating with a lot of conflict and dissonance on a very daily level.

Keyframe: And in Red Flag it comes out funny where in Rubberneck it becomes sinister.

Karpovsky: Exactly right. One thing I’d also like to add, thinking back on Beeswax, which I haven’t done for a while: it’s also maybe one of the few times if not the only time I’ve ever played a nice guy. I usually play jerks or cynical bastards and in that movie I feel like i was really genuinely a pretty honest and righteous fella. It’s funny when I think back that was my first role and I’ve never really played that role again for some reason. Shortly thereafter I was cast as a jerk and I’ve stayed a jerk pretty much ever since.

Keyframe: Do you like being typecast as a jerk?

Karpovsky: I never said I was typecast, but I am cast repeatedly as a jerk. I wouldn’t say typecast because I think people have different ideas about being typecast—some people think it’s based on a recurring pattern and others think it’s based on who you really are. But anyways, I enjoy playing the jerk—I do. It’s fun for me to do because I’ve found there’s only a handful of ways you can even portray a straight man or a nice guy, but there are an infinite number of ways to play a jerk and that versatility, that spectrum, is something that I’m interested in.

Keyframe: Let’s talk about Rubberneck and Red Flag then, because you’re playing a jerk in both of them in different ways. I understand you shot them simultaneously. Why motivated you to work that way?

Karpovsky: They were my fourth and fifth movies and one thing that I’ve noticed from working on earlier movies and and acting as well is that you can lose perspective very easily and you can lose enthusiasm very quickly, especially if you’re working on lower budget movies where you’re carrying alot of the weight and there’s not really a delineation of responsibility and you’ve got a pretty big load. It can make you tired. It can make you disengage emotionally and creatively from the endeavor. Hoping to sidestep that trap, I basically tried to do two movies more or less at the same time that were very different tonally. Even if it took twice as long for them to individually come out, that was OK. I just wanted to make sure I had a real ‘escape’ when I moved from one movie to the other, temporarily. So, we shot Rubberneck first but before I was able to roll my sleeves up and get into the edit, we started Red Flag, and before I was able to get into the edit of Rubberneck, I had to edit Red Flag, and that allowed me to come back to one project pretty refreshed and enthused, and very eager to explore this new place.

Keyframe: That could be the reason they have parallel structures, in some ways.

Karpovsky: That could be a reason they have parallel structures; another reason is because I only know how to tell stories with one structure, I think time will tell. [laughs] There are also similarties to Woodpecker and to The Hole Story as well: they’re all kind of sort of the same length at eighty or eighty-five minutes. My editor joked that you could play all four of them at the same time and they would all rise or fall, in terms of character arc, at the same time, but we’ve never done tests.

Keyframe: I guess he would know more than anybody.

Karpovsky: Exactly. She would.

Keyframe: I was reading another interview with you and I’d noticed that someone compared Red Flag to Michael Winterbottom’s The Trip, which I think is one of the funniest movies of the last few years.

Karpovsky: It was a huge influence. I really liked it. I just love Michael Winterbottom to begin with, especially his comedy, like 24 Hour Party People and Tristram Shandy. I also just kind of get a kick when people play amplified versions of themselves if I’m initially interested in who they are. Larry David, Woody Allen, Louis CK, you can argue that all these guys are playing comedically amplified versions of their real personas, often using their real names. Stuff like that I like doing; I think it’s fun, I think it’s interesting. Those guys just did it with This Is the End, I don’t know if you’ve seen it. I think they did it in a more broad tone, but the idea is driven by the same sentiment. The Trip was a huge influence because of that. Two guys [in Red Flag] playing themselves, going on a road trip–the similarities are pretty evident.

Keyframe: Steve Coogan is an actor I enjoy, but I think Winterbottom has a special way with him. There’s something to be said for getting the best out of an actor and that relationship between actor and director.

Karpovsky: That’s true, I think his best performances have been in Winterbottom’s movies, but there are a few exceptions, I enjoyed his small roll in Tropic Thunder. You’re right though, there are certain directors that know just how to exploit what certain actors do.

Keyframe: In terms of being in tune, let’s talk about Girls. As the story goes, you met Lena Dunham at SXSW, you subsequently did Tiny Furniture, and the rest is history. Once you were friends, how easy was it for her to convince you to do a TV show as you’d never done one before?

Incredibly easy! Look: it’s HBO, which is great; it’s a TV show, which is for me weird and foreign and interesting; and it’s Lena Dunham. I was just a huge fan of Tiny Furniture. I was really happy with the way that congealed. If she wanted to take me and Jemima [Kirke] and Jodie [Lee Pipes] from Tiny Furniture to a web series, to anything, I would have followed. There was never any hesitation.

Keyframe: It always seems to me in the way that Girls is written, and the development of the characters, that it’s a collaborative process, and given that you’re all friends, that’s how I envision the way that show is created. How far off am I?

Karpovsky: Lena spearheads the writing, and I personally am not involved in the writing at all. I don’t know that any of the other actors are involved in the writing, but I don’t want to speak on their behalf. The scripts come to us and they’re really pretty wonderfully written for the most part. For me personally, I don’t feel any compulsion to improvise, to tweak really. Since Lena knows me pretty well and there are alot of similarities between this character and who I am—who I was earlier in my life—I feel like it’s already ready to go. So it might not be as collaborative creatively as you may think. I just kind of get the script, I try to understand it, and I try to execute it as closely to the way that it’s written on stage. I also don’t really have conversations with her about where the character can go or what new things we can introduce in the future. I leave that to her and her producers to play with, because I trust her and I trust her sensibility and I feel like it’s done good stuff for the show already and I don’t want to mess with it.

Keyframe: That’s surprising. The way that you and Adam Driver’s roles play out seem so fleshed out, but so different from the other characters, that I’d always imagined you were furtively writing lines in the back room before shooting.

Karpovsky: No, that’s not going on. I think that sentiment is a testament to just how perceptive Lena is and how good of a writer she is, that she can capture those sorts of things, more than any other collaboration that’s going on.

Keyframe: Speaking of Adam, you recently finished shooting Inside Llewyn Davis, the new Coen brothers film, which he also features in. I’d read that you hadn’t seen it yet in a recent interview. Still waiting?

Karpovsky: I haven’t seen it. I understand that it might be coming to a festival in these woods at some point soon so I hope to see it then. I had a few friends that went to Cannes and they saw it, and Driver saw it here at a local screening. I know that I’m not cut out, that’s all I know.

Keyframe: How was the experience of working with the Coen brothers? You’re on the record as a big fan of theirs.

Karpovsky: I’m a huge fan. I was only on there for a couple days, but it was pretty special. They’re probably some of my favorite filmmakers working today. One of the things that was really nice is that they have such a specific cinematic sensibility that comes across in their films, and if you’ve been watching their films, as I have, for the last twenty or thirty years, you can dial in to what they want pretty quickly. In that sense, they don’t really need to direct you too much. Their body of work is already a central foundation for what they want out of you. So that was interesting. I’ve never worked with ‘masters’ before, where you already know a lot of what they want based on the very specific and idiosyncratic sensibility they’re constructed over the years.

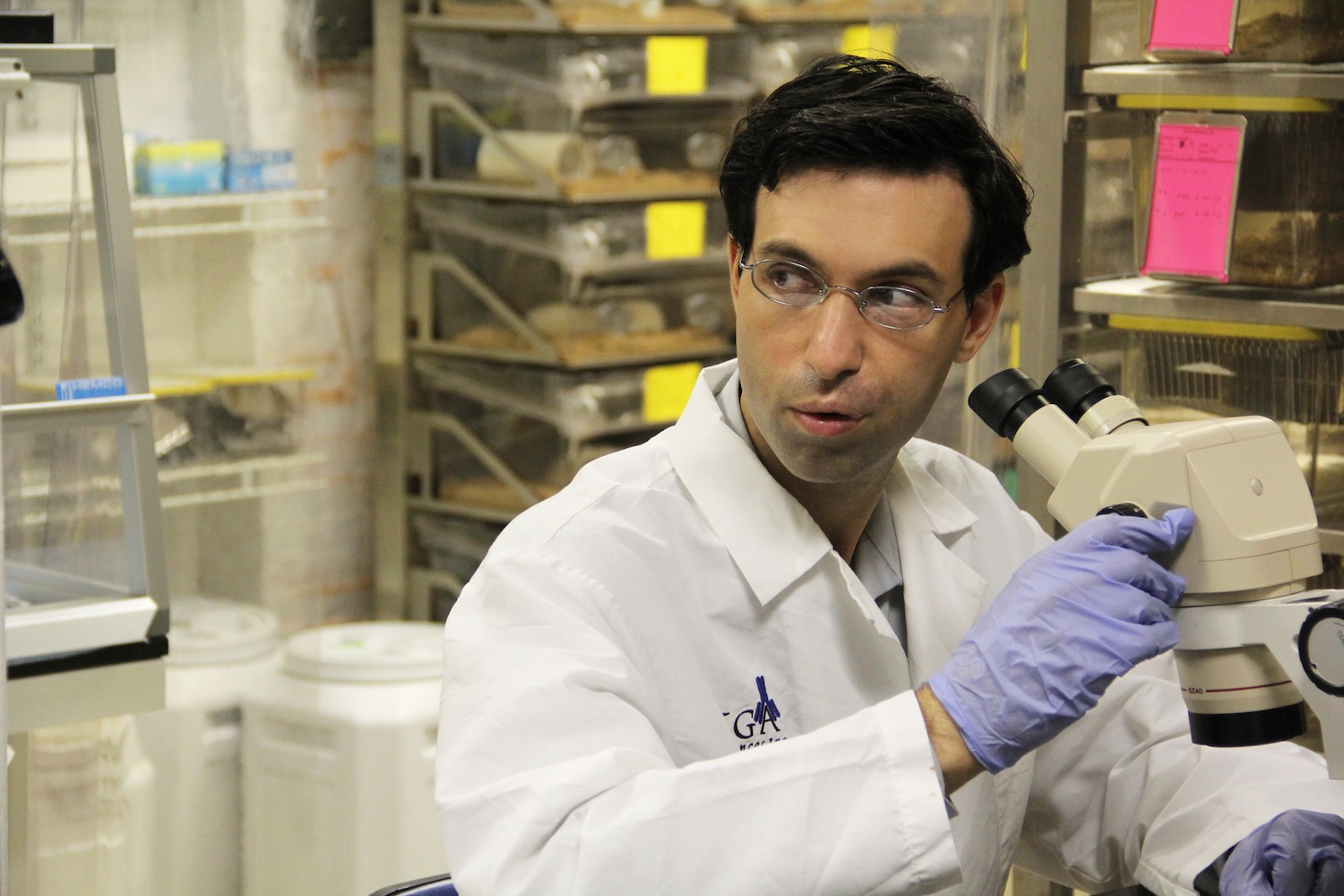

Keyframe: I noticed when I was going over your press materials that you majored in Visual Ethnography at Oxford. Do you think that ended up having any bearing on what you bring to your films? In almost everything you’ve done save Red Flag, there’s a preoccupation with the ‘scientific method’ or some perversion thereof.

Karpovsky: That’s interesting. I can’t say I’ve consciously made that a part of anything I’ve done over the past few years, but what I can say—and this may be a stretch, I’m not sure–is that what they taught us are ways and tools of analyzing cultures and breaking down their behavior, their histories, their traits and rituals into elementary parts that have universality to them. Then to be able to combine and recombine those traits as a way of analyzing differences between cultures. They showed us ways of deconstructing parts of a culture and its personality and its history very vigorously, and I may be going out on a limb but that one of the things I try to do as an actor when I’m given a script. Not in Girls so much because I know that character, but in other things, I try to break them down into elements of those personalities that I can combine and recombine in different ways until I feel like it’s works, based on conversations I have with the director or the actors. And also as a director I’m trying to do the same thing when I’m writing a character or when I’m trying to communicate what I want in a character, breaking things down in into their constituent parts is very helpful, and that they teach us in Anthropology. It sounds like I have to go, they’re grabbing me for another interview.

Keyframe: Can I ask you one more silly question?

Karpovsky: Sure.

Keyframe: I know it’s taken you a bit of searching to get where you are now. After college, did you ever work at a Café Grumpy in real life, like your Girls character Ray?

Karpovsky: The closest I worked in was place called Grendel’s, which actually sounds a bit like Grumpy, which I think is still around in Harvard Square. I worked the service bar, so I was basically the bartender in the kitchen which nobody sees. So in addition to doing drinks I was doing ice creams, fondues and coffee. That’s the closest I ever came to being a barista.