Peter Watkins’ cinema is known for its difficulty, its intractability, its utter lack of compromise. Several of his films are also known for their daunting length. His arthouse breakthrough, Edvard Munch (1974), was 210 minutes long; The Freethinker (1994), his biography of August Strindberg, is 276 minutes; and his final film to date, La Commune (Paris, 1871) (2001) is 345 minutes long. But in 1987 he released what in some ways has come to be his definitive project, The Journey, an 873-minute global documentary focused on nuclear proliferation, the military-industrial complex and the media’s collusion not only with our leaders but with a generalized incapability to envision a better, safer world.

Whether The Journey is Watkins’ most successful film, simply by dint of being far and away his longest, is an open question. However, the scope and ambition of the film, and its patience in articulating connections across multiple scales of living (local/global; First/Two-Thirds World; family/nation) is unparalleled. What’s more, Watkins takes the time to relate history—in particular, photo documentation of the devastation visited upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the atomic bomb—to the present. (One refrain involves photojournalist Bob Del Tredici showing and discussing his images of factory production of nuclear warheads.)

But above all, Watkins emphasizes that people from all walks of life are connected by the nuclear issue. Ordinary citizens get involved, learning more, and the film is both a document of that process and an attempt to further said process. “This film is about systems: the systems under which we all live, and the mechanisms by which they deprive us of information and participation.” Most impressively, Watkins does not exempt cinema itself from this collection of systems. The problem of making and of watching a fourteen-and-a-half-hour documentary about one of the grimmest subjects imaginable is by no means lost on Watkins. In fact, it is a kind of intellectual ghost that haunts The Journey as an endeavor.

Watkins notes how much was being spent on the global arms race at the time, using the statistical metric of $1.5 million USD per minute. He therefore comes into the film periodically with his voiceover to remind us of how much money has been devoted and diverted to this obscenity during the very time it takes to watch his film. In this regard, Watkins is exercising several simultaneous critical maneuvers throughout The Journey, some of them auto-critique and some of them aimed squarely at his audience.

While the primary purpose of the running tally of nuclear arms expenditure is an indictment of the right-wing defense culture of the Reagan/Thatcher/Mulroney eighties, The Journey also implicitly challenges the idea of armchair radicalism, of “activism through spectatorship.” There is a political impact in Watkins’ fourteen-and-a-half-hour film that is knowingly ambivalent. On the one hand, Watkins the media critic insists that they adequate engagement with a structural geopolitical issue such as nuclear proliferation requires expansive time. On the other hand, The Journey throws down a challenge to those who are able to devote the time to watch it in the first place. What are we doing to make activism and social justice a part of our lives? (Each reel ends with a question mark, and it could be taken as a placeholder for this very conundrum.)

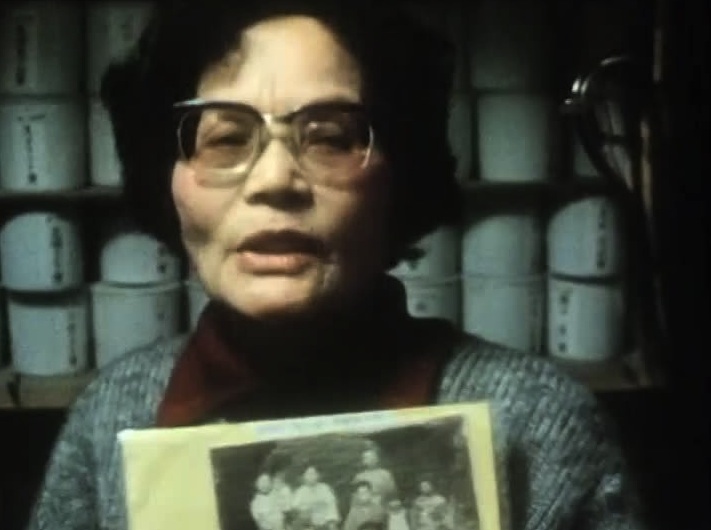

This is why The Journey situates itself among activists as well as ordinary families and groups who simply share Watkins’ concern for the future of the earth. These are people who, to one extent or another, have rearranged their lives in order to make time to fight the bomb. They have made action against nuclear weaponry, on both a local and a global scale, a part of the new fabric of their daily living. The Journey itself, over the course of its production, also becomes an organizing tool, as several of the participants wanted to meet each other after viewing footage of people in other parts of the world. Seeing that there were others who shared their concerns, the participants effectively came to comprise a pre-Internet global network, which is undoubtedly part of Watkins’ aim in making the film on an international scale, and part of The Journey’s didactic, extra-filmic strategy.

As we watch, we learn more about the problem not only of nuclear weapons but the way that they are but one (rather striking) example of how citizens’ desires and demands, or even our right to know basic information about the actions of the state, are radically marginalized. So The Journey as a film represents an attempt to explore this problem with all the complexity it deserves. Watkins focuses on specific local problems, and then makes a slow, careful argument about how all such local activities of the state are subtended by a much broader world-system, and that a fundamental component of this system is an information management scheme which reduces political questions to photo ops (such as the highly stage managed “Shamrock Summit” between President Reagan and PM Mulroney), or pulverized clips and soundbites within a rapid-fire news format. All of this, Watkins insists again and again, bludgeons the spectatorial consciousness, to the point of a kind of psychological acceptance of helpless dependence.

At the same time, as Watkins moves through The Journey, logging the amount spent on nuclear weapons during the running time—a politicized form of structuralist self-reflexivity—he is actively demonstrating just what cinema cannot do, and why even a work as unconventional and high-minded as The Journey is deeply limited, if not a kind of Western luxury. While it is necessary to recompose our way of life, and especially our manner of taking in critical information about subjects such as the life and health of the planet, in order to become smarter and more engaged, we must also recognize that this option, this potential change, currently exists only for a select few of the world’s citizens.

The Journey, then, as a fourteen-and-a-half-hour-hour experience, can be considered as both a necessity and an expenditure. The filmmaker states, “two of our principle concerns in this film are money and time, and the way that we use them on this planet.” We must understand that our current time-models for learning and for leisure (to say nothing of the hard distinction between the two) will always place tight controls on how much we as citizens can know about the systems in which we are ensnared. It’s not just that news stories are too short or edited too rapidly, although Watkins sometimes tends to focus on the production angle, as if it were a unilateral attack perpetrated upon unsuspecting citizens. His point goes deeper than this.

We actually have much more information at our fingertips now, and it is somewhat harder to control, than it was when The Journey was made, although much of what Watkins tells us is still quite true. But instead of being kept in the dark by a handful of corporate interests, in a directly propagandistic way, we ourselves are shaped by the clipped, censored, and meme-controlled media landscape. That is to say, our attention spans are colonized by these dominant forms and formats, so that the fact of having more choices and more access represents no real threat to the power structures that promote anti-democratic agendas.

The Journey is, among other things, a documentary about its own length and its slow, careful deliberation. And at the same time, this time of viewing and understanding is a commodity that cannot be so easily extracted from, say, the women of the farming collective in Mozambique, or others who might be featured in a more contemporary version of The Journey—the working poor in North American slums, or the various colonized and marginalized indigenous peoples of the planet. The Journey demands sustained attention from those of us who can afford to pay it, even as we convince ourselves that we are too busy to give it our precious time.