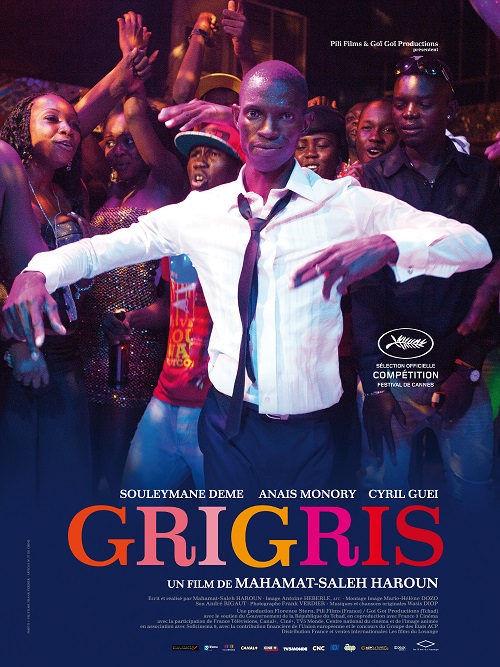

Mahamat-Saleh Haroun‘s Grigris is at first glance a touching, sympathetic and entertaining look at a disabled dancer and his prostitute girlfriend as they find themselves in trouble with smugglers. More importantly, this film, which premiered in Cannes and just screened at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, is an insider’s attempt to show complicated social and cultural politics of Chad in particular and Africa in general. Haroun, with whom we talked at Cannes, explains the relationship between politics and romanticism, talks black-white dynamics and addresses the question of why there are no bees in his film.

Keyframe: How did you find your character? Was he working as a dancer?

Mahamat-Saleh Haroun: I saw Suleymane Démé during an official dance performance, on stage. It was February 2011 in Ouagadougou (the capital of Burkina Faso). It was dark and then this amazing creature appeared on stage, with his hair dyed white like some football players do, holding his leg the same way you see him in the film—like a gun. There was something so striking and unique about him that I immediately thought: this is my character.

Keyframe: So the idea for the film started with this meeting?

Haroun: No, it happened before. When I got to know a story about the smugglers in Chad, this is what I was planning to make a film about. I know people in my neighborhood who are in this business. I had a camera, so I went and shot the whole thing—how they pack the fuel, swim across the river, etc. At the beginning I even wanted to make a documentary, but of course they did not particularly like the idea, because they don’t want their [illegal] work on film. Some of them refused to participate, but others, mainly younger, treated me as an elder and accepted me, like an older brother. This is how I started working on this subject.

The first draft of the script was more of a thriller, and I really wanted to avoid that. I didn’t want to make a pale copy of a Hollywood film. I was stuck, I didn’t know what to do. And Grigris—Suleymane—appeared in my life as a gift from God, a magic amulet. I thought to myself he’s the one who’s going to help me surpass making a simple genre film.

Keyframe: Was it difficult to work with someone who had absolutely no experience in acting?

Haroun: Surprisingly it wasn’t. As a dancer, he has a sense of rhythm, tempo. What all artist are doing is trying to find what’s right for their work. He’s also looking for it and it made it all much easier. He also has this amazing intelligence, great presence and this kind strength or force coming straight from nature. It was all natural for us.

Keyframe: In the film there is a constant presence of contradictions: glamour and poverty, night and day. Also Grigris, the main character, has the same balance in him—the disability and his passion for dancing. Were you aware of that when shooting?

Haroun: I wouldn’t call it contradictions—it’s more of a contrast. And where opposites meet, something new can be brought to life, there is a result [out of such meeting]. It was all intentional. During the daytime they do legal things—he’s a photographer—and then in the night he becomes somebody else, a true character. As for Mimi—I have a lot of prostitutes in my neighborhood, who during the day want to be respected, they have families, children. But in the night they also turn into somebody else. I wanted to show the marginalized people looking for a solution, finding sense in their existence.

Keyframe: I feel like it is music, that is the heart of the film. It really reflects who Grigris is, when he’s dancing…

Haroun: I think so too. When we started working on it we flew to Burkina Faso with the musician Wasis Diop. We saw a performance just like Grigris’. Later Wasis told us that every time he looks at Grigris and then at Suleyman he goes to his room and works on his computer to modify the structure of the music. So it has been done in accordance with his own way of dancing. Wasis, who was a photographer before, was so touched by Grigris, that he wanted the music to be his true companion.

Keyframe: Why did you decide that the main female character has to be a prostitute?

Haroun: She’s a prostitute, because she’s considered a bastard, have father remains unknown. [In our culture] it’s very important to be integrated: we know who you father and mother is so we can marry you. If you have no parents you have no roots and such individual is not welcome. To be accepted she needs to put a wig on and look for love in maybe only possible place for her, which is the prostitution business, where you can pay for love and get it. She’s been rejected, excluded. And the same thing goes for Grisgris, who’s handicapped, has a dead leg. When you are in prison, you meet other prisoners. When you’re a reject, you meet other rejects.

Keyframe: Some claim the relationship between Mimi and Grigris is more political than romantic. How do you respond to that?

Haroun: [Like I said before] I really think in such places [as I portray in my film] you get to meet rejects like them. They recognize themselves as one of a kind and fall in love. So in my mind it is romantic and not political. Maybe people who say such things don’t know romanticism well enough? All the reviews have some standpoint about Africa to offer, everyone has their own opinion. Even if I talk about my own country, there will always be someone who’ll be like: ‘Oh, but I know Africa better and it’s not like this.’ After the screening of this film [in Cannes] there was a guy who came to me and started saying how well he knows Africa and that he travels a lot. I was wondering: what is he trying to say? And he said: ‘Where are the bees? There are a lot of bees in Africa and absolutely none in your film!.’ If there are people denying your film truthfulness because of such thing, well… It’s a fantasme .

Keyframe: Most of Mimi’s clients are white. Does this reflect the current situation in Chad, where many natural supplies are being taken over by western companies?

Haroun: It’s not really that. By the way, not all of them are white; there is a third man, who’s black. We have a French military base in Chad and when you go to N’Djamena you see a lot of French people. The men who inhabit the base have no families and they need women. I don’t know why, but they do. So they are meeting with the prostitutes, and that’s the everyday reality. But also Mimi is looking for a father figure there. Her own father was French and she’s never met him. I don’t criticize her. I don’t make films to criticize such things. There are lot of people here [in Cannes] or Nice, having sex with older women because they are looking for their financial support. But it’s just a detail.

Keyframe: This question was an attempt to link the film with the social situation in Chad. And there are issues in Grigris—like health, prostitution business, financial divisions…even if unintentionally, you are making some references here.

Haroun: Absolutely. It deals with all of those things. But more important are maybe the environmental context and, of course, the social issue. That was the challenge for me—to bring all those elements into a single film. I think with enough courage and thought it is possible to do that. The film definitely paints a certain picture of Chad. I didn’t want to make a simplistic film, like Hollywood filmmakers often tend to do. Someone gets killed, there’s a huge manhunt etc, etc… I wanted to show all the facets of the city.

Keyframe: Were you ever concerned that Grigris’s disability might take away from the narrative itself?

Haroun: Yes, absolutely, that was a real danger. I didn’t want people to pity him; my goal was exactly opposite. I wanted to show someone, who first of all has a life of his own, a career and a passion. And who, by the way, also happens to have a disability.

Keyframe: In your film there is a village where only women live. They form a strong community and take radical actions. Is this a realistic vision or just an artistic creation?

Haroun: I can’t say it is a realistic portrait. It’s a rather utopian desire, if you like. What makes Grigris different [in the eyes of the women from the village] is that he’s not like their men, husbands, brothers. With his fondness of children and ability to take care of those around him he really stands out. The women have solidarity, this is their strength. They also have desire for such different kind of man. With his qualities he corresponds with their needs and desires for an ideal male partner. Fifi, Mimi’s friend, has left the city and stopped working as a prostitute to move to the all-female village. She’s been accepted there. All of them in a certain sense abandoned their previous lives to create something new together. Fifi says to Mimi, at certain point: ‘Does he know who you are?’ and the response is: ‘Don’t tell him. With men, you never know.’ This is a philosophy of all those women. They are not criminals, but they kill this one man [together]. Afterward there’s just one big silence, as if they were asking themselves ‘What have we done?.’ In Africa, to build something new, to start something, you need to sacrifice something else first. In a symbolic way the killing of this man becomes such sacrifice, the beginning of a new community.

Keyframe: Was this project an enriching experience for you as an artist?

Haroun: I think that for an artist a challenge always is just trying new things. [We did things that] in a normal production no one would accept—it’s risky to combine all those styles, smoothly jumping from comedy to tragedy. But I think that if you’re free and nobody’s counting your money… nobody puts money on me, planning a huge box-office hit. If I was a horse, they wouldn’t bet even one dollar! I’m from a country where life is like walking on a rope with no safety net, this is how I felt growing up. If you fall, that’s it. But in my head, I kept telling myself, that falling is not important. What is, it’s whether you can stand up and walk again. Sometimes it’s just your heart that you have to follow.