The following is the fourth in a series of on-set reports by producer Jeremiah Kipp on God’s Land, a feature film written and directed by Preston Miller. God’s Land will be viewable online exclusively at Fandor this weekend, Friday, October 27th – to Sunday, October 29th, Miller’s first feature, Jones is currently available on Fandor. The entries are reposted here with the kind permission of The House Next Door (who are re-posting the odd numbered entries of the production diary).

As Mr. Kipp details in his 4th production Diary, there are many frustrating challenges to shooting outside at night with a small crew. As the early AM hours approach, bundles of cables grow heavier, eyes grow more red with each take, and everyone on set would give their left arm for an extra intern or production assistant or a dedicated grip (Oh what I would give for a dedicated grip). But the crew soldiers on because that’s what good soldiers do. And Kipp, fighting exhaustion, is the man on the front lines, happy to provide us yet another thoroughly entertaining and educational production diary. – Paul Meekin, Keyframe

I was away from God’s Land for a few weeks, producing an independent feature in Sarasota, FL. It was a rigorous experience, and while we are not supposed to talk about “project mayhem,” I can say that we were chased by alligators in a rubber raft, I saw armadillo and wild boar in the wetlands, shot on planes and speedboats over the Gulf of Mexico, filmed an elaborate and risque magic show, and set up car rig shots on designer cars that, when fitted, seemed like vehicles from Mad Max. Ah, yes, “project mayhem” was an intense and enjoyable time, but when I come back to NYC, I’m dog tired and it’s hard to settle back into the rhythm of God’s Land, which is slow, meditative, put together by a handful of loyal crew members, and hangs together by what feels like cardboard boxes and chewing gum, and the will of director Preston Miller.

Our latest shoot involves night exteriors. I think it was Repo Man director Alex Cox who said that for all the pain that has been put upon screenwriters over the years, they have the sweetest revenge when they write the words “EXTERIOR: NIGHT” because these scenes always involve more lighting, more cable running, more of a heavy workload—and considering Preston’s crew size is generally three or four people, it stretches the production incredibly thin whenever he has a scene like this. Since I’m still wiped out from my previous feature, I wonder how much support I’ll be able to provide—I look and feel like death warmed over. House Next Door editor Keith Uhlich didn’t even recognize me when we attended a screening together, since I was pale, hollow-eyed, and seemed to have come back from a war. I figure, what the hell, maybe I should use this persona in God’s Land—and enlist myself as an extra. Since with my headband, sunglasses and camera I look like Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now, I play a rock and roll journalist/photographer during one of our big scenes.

The problem with lighting night scenes isn’t as much lighting the people in the frame, who can either go dark Gordon Willis-style or be lit with classical three-point lighting. More important is lighting the background to provide depth to the frame, to provide a reference of where the characters are, and if you only have four lights without heavy wattage and that small lighting package is nevertheless tripping the circuit breaker from the lines you’re running from the house, you’re walking into an independent film horror show. Director of Photography Arsenio Assin and I perform the grip and electric duties, and I’m reminded that, on most night shoots, you need at least six guys to do this properly. Our stalwart Assistant Director, Alex Gavin, occasionally lends a hand, and even Sound Mixer David Groman offers to help when he’s not rigging mikes and camouflaging his own cables behind trees, bushes and flowerbeds.

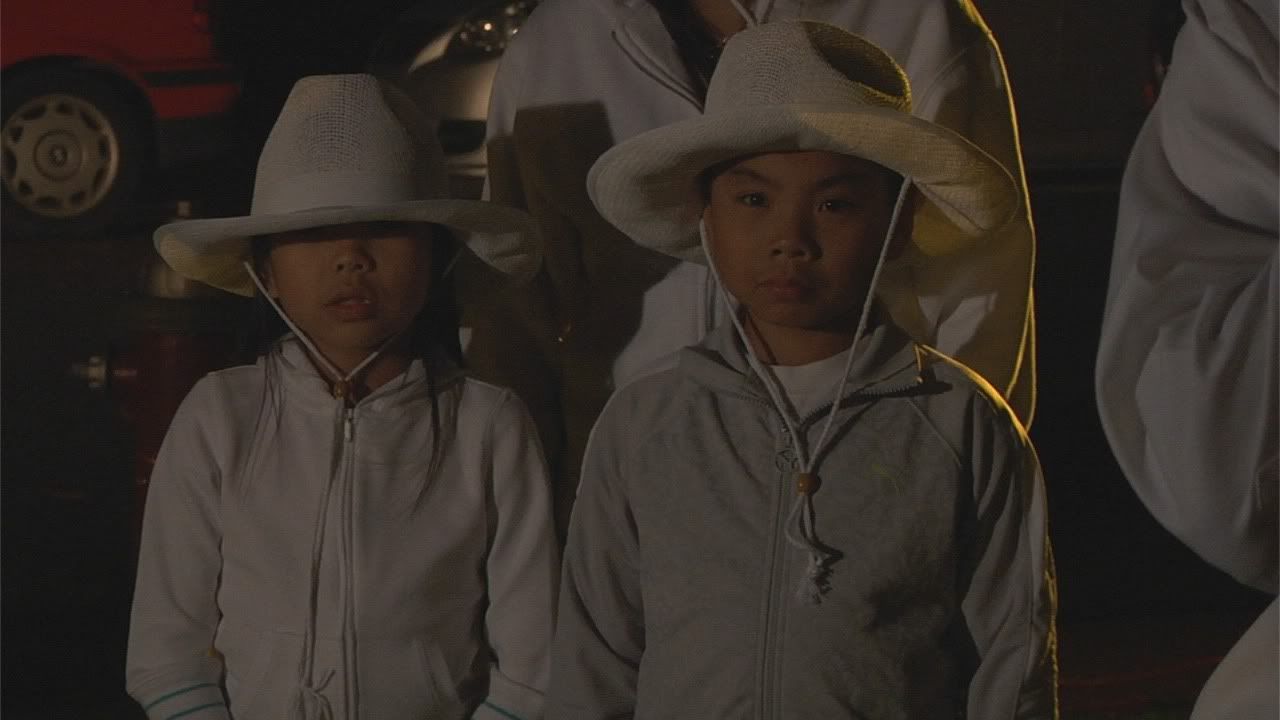

Still and all, Preston is in full-on Captain Ahab mode and remains undeterred by the struggle; I don’t think he considers it all that much. While he’s friendly, smiling, polite and, generally, an all-around nice guy, he has the tunnel vision of a director. He tunes out these problems and does his job, which is concentrating on the performers. The night shoot involves a large group of cult members during the darkest hour of their faith. There’s a quietly intense speech given to the crowd—all dressed in white jumpsuits, cowboy hats and boots—informing them that this moment, while not literal suicide, should feel like standing on the edge of a great abyss.

The script, as written, demanded a Steven Spielberg budget involving 350 extras, helicopters, policemen, an army of reporters and onlookers—and when Preston was unable to raise the millions it would take to shoot that version of the scene, it took on a more intimate quality, more about the disintegration of a belief system. I often say that the making of a movie is the movie itself, and Preston’s dream of a multi-million dollar spectacle scene has dissolved into cold, harsh reality. The cult members are facing the pain of that reality as surely as Preston is. The handful of lights and crew, the grueling endlessness of night shooting, which gets us home at about four in the morning, the frustration of not having enough house power to draw on—this, too, is a harsh reality. And Preston allows these things to happen, so in his own gentle, quiet way, he lets real life inform the scene. I don’t think he’s even aware of it, and even if he was, I doubt he’d care. When you’re making movies in this low-budget way, getting the shots done puts the director into a kind of trapped survival mode where he’s racing against the clock, and against fatigue and the frustration of his team.

The moment involves our doomed protagonist, Hou (Shing Ka), and the cult company man, Richard Liu (Wayne Chang), during a scene at the film’s midpoint, which involves Hou releasing a hint of emotional baggage—for much of the movie, he keeps these parts of himself very close to the vest. But of course he’s unloading to a representative of the cult who is slick and tows the party line, so it’s like releasing into a vacuum. Wayne, whose character earlier in the night was having a quavering meltdown and had to lower his head and collect himself between takes, is back in the smooth operator mode, and Shing, throughout this evening, has been opening himself up more than I’ve seen him do before, even in person. He has a cool persona, a kind of rock star aloofness that I couldn’t see past when I first met him.

It was only when I saw him interacting with the actors playing his wife and child (Jodi Lin and Matthew Chiu) that I saw the kindness, depth and humanity underneath. In these scenes, we see the cracks forming in his façade, and through the cracks we see a glimpse of pain—which is the pain of not knowing whether this quest has all been for nothing. It’s powerful to witness a man as strong and secure in himself, and Shing allows us to glimpse that vulnerability. His face is as much an emotional landscape as seeing twenty white-cloaked figures running across a lawn in torment, and yet Shing is finely calibrated, very controlled. We go up to four takes on the scene, and Shing slowly opens himself up, allowing more of the ache to slip through. Preston is profoundly moved by his performance; it may be the moment he and Shing are closest as director and actor. We shut off the lights; the long dark night of the soul is over.