At Halloweentime, fans of shocks and tingles have thousands of movies to choose from, in a wide range of subgenres, subjects, and tones. Books can be written on the history of the horror pic, from the atmospheric black-and-white movies from the century’s first half to the modern, low-budget splatterfests that routinely bypass theaters and end up in cruddy VHS video boxes or streaming online. However, one film can be described as the lynchpin for all of it, the centerpiece of history. It was the film that gave a farewell embrace to the old, while simultaneously ushering in the new. It was a genius product of its time, and yet it somehow remains timeless.

That film, Night of the Living Dead (1968), was the debut feature of director George A. Romero. A Pittsburgh resident, Romero and his colleagues had been making commercials and industrial films before deciding to indulge in the horrific for a budget of $114,000; they might not have known what they were in for, but they must be credited with a certain amount of inspiration beforehand. The movie opens, in old-fashioned black-and-white, on Barbra (Judith O’Dea) and her brother Johnny Blair (Russell Streiner) making an annual, lengthy drive to a graveyard to change the flowers on a relative’s grave. Barbra is meek and scared, while Johnny loudly gripes and makes funny voices. His Boris Karloff (“they’re coming to get you Barbra!”) is an early acknowledgment of horror films past, which will quickly be chewed up and spat back out.

A “ghoul”—or a “thing”—(the word “zombie” is never used) begins shambling toward Barbra. It’s brutal. It’s the ultimate taking of power, a true moment of horror. The mindless thing is focused on Barbra, who holds her head down, as if unable to do anything but hope the danger passes by. Fortunately, Johnny steps in and becomes the first victim of the plague, but Barbara becomes nearly catatonic for the rest of the film. She’s a constant reminder of the frailty of human flesh and spirit, and just how terrifyingly close we are to the zombies.

‘Night of the Living Dead’

From there, she meets the hero of the movie, Ben (Duane Jones). Jones, who died in 1988, was a trained actor and a theater teacher. He was also an African American. Romero has claimed that race had nothing to do with Jones’s casting, merely that Jones gave the best audition for the role. And, indeed, it has been noted that no one in the movie ever makes reference to Ben as a black man, not even the uptight, contradictory Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman), who could very easily have conjured up a racial slur or two during their many onscreen arguments. Romero must have known that he was doing something unique; this was during the Civil Rights movement, although Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination took place after the filming was completed and before the movie was released. For many Ben became a symbol of both African-American oppression (especially given the film’s ending) as well as heroism. (In the mainstream, Sidney Poitier was getting credit for doing the same, but without the force, Jones has in this movie.)

Ben, Barbra, Harry, and a few other survivors—Harry’s wife Helen (Marilyn Eastman), Tom (Keith Wayne), Judy (Judith Ridley), and Harry and Helen’s 11-year-old daughter (Kyra Schon), who sustains a zombie bite—hole up in an abandoned house. It’s all geographical perfection: inside vs. outside, upstairs vs. downstairs. One of the goals is to reach a gas pump outside, fuel up one of the cars, and make a run for it, although there are complications (keys for the gas pump, etc.). Not to mention that there’s a surprise waiting somewhere in the house. But then the argument comes up as to which is safer: going into the basement, which is easily barricaded, but leaves no other way out (Harry’s choice), or staying in the main house, with its many options (Ben’s choice).

Early viewers focused on the gore, which included zombies munching on flesh and intestines (really pork and chocolate sauce), as well as a topless female zombie. Gore like this was still fairly new to the cinema—Hershell Gordon-Lewis was officially credited with inventing the gore flick in 1963—and several pundits tried to discourage people from seeing Night of the Living Dead, fearing deep, lasting psychological consequences. But Romero displayed a showman’s mastery, using deception to sneak in the point of his story. In actuality, the point of the movie is not the zombies or the gore, but the behavior of the humans inside the house. One human assumes the role of leader, almost without thinking. It’s just the natural, animalistic order of things. Other humans fall in line behind him, but others challenge him. The zombies outside create a certain amount of tension—an attack could come at any time—but during the wait, the humans create the rest of the drama themselves.

In another brilliant twist, Romero occasionally gives us glimpses of the outside world, in the form of TV news. At some point, a band of gun-toting yahoos (“they’re dead… they’re all messed up!”) goes out hunting, their weapons giving them a different kind of authority. It’s clear how Romero feels about these guys, and yet they are in charge, with reporters asking them questions about the entire ordeal. Power is so easily wrested away in Romero’s world, for no good reason at all.

Romero would go on, during the rest of his extraordinary and largely unsung career, to point out more foibles and hypocrisy in human behavior, while disguising his commentary under horror and spectacle. In other words, he makes movies that Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson) in Sunset Boulevard might approve of. (“I just think that pictures should say a little something.”) In the first sequel, Dawn of the Dead (1978), which was, of course, filmed in color, given that it was now the modern era of horror, his topics of choice included consumerism. Images of zombies shambling mindlessly around a shopping mall, confused by the escalator, were relevant then and even more relevant now (picture the zombies staring emptily at cell phones). Day of the Dead (1985), made at the height of Reagan’s reign, made a commentary out of military intelligence and weapons stockpiling.

A master filmmaker of Romero’s caliber was, of course, marginalized (Orson Welles-style) and he worked only sporadically (in a career of nearly fifty years, he has completed only sixteen features). But twenty years later he came back with a masterpiece, a full-fledged summer blockbuster backed by a major studio, Land of the Dead (2005). (It didn’t exactly set any records, but it grossed around $20 million and at least made back its budget.) Along with that year’s War of the Worlds and Red Eye, it was one of the first movies to acknowledge the fear and confusion instilled by 9/11. It contains tales of a high rise, a wealthy megalomaniac, the haves and have-nots, and—again—issues of leadership and race (an African American becomes a leader of the zombies). The fifth film, Diary of the Dead (2008), tackled media saturation, and the unfairly maligned sixth, Survival of the Dead (2010), tells the story of an old-time human feud in the midst of a zombie apocalypse.

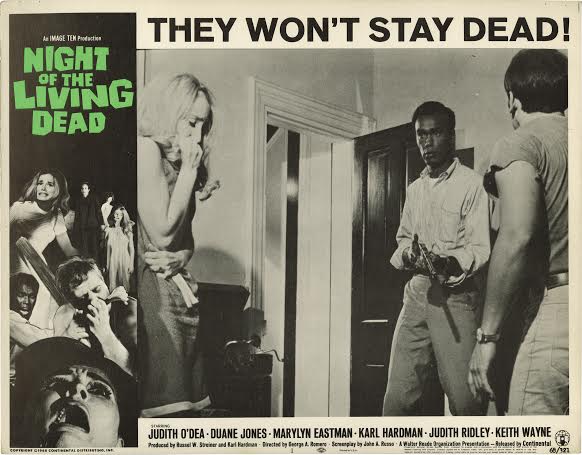

Lobby card for ‘Night of the Living Dead’

Of course, remakes and ripoffs followed too. Because of an error, the twenty-eight-year-old Romero never copyrighted the original film, so it’s all fair game. (Imagine if he had copyrighted the term and the image of the zombie; his career would have been quite different.) The very funny The Return of the Living Dead (1985) was created by Night of the Living Dead co-writer John Russo; makeup artist Tom Savini directed an official 1990 remake, and Zack Snyder had a genuine blockbuster with his remake of Dawn of the Dead (even though it offered nothing that the original hadn’t already done better). Other ripoffs happened, too, but they are barely worth mentioning.

This would be a good moment to discuss the “fast zombie” phenomenon. Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002) introduced the concept of zombies that run and descend on victims like packs of jaguars. It was a critically acclaimed cult hit, despite the fact that the cruddy-looking movie is an obvious knockoff of Day of the Dead and other 1980s horror flicks. The fast zombies, copied in several other movies after, including Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead, simply provide a two-second jump-shock, nothing more. They have nothing to do with the original horror that Romero invented, the unexpected way that a slow, shambling thing can—inevitably—make its way toward you. Romero’s method is more primal, more nightmarish as if your feet are planted in the mud, and as if the attack is personal.

In the years after its original money-making and outrage-inducing debut, Night of the Living Dead has taken its place as a classic. In 1988, John Kobal published a book-length poll of critics and filmmakers, John Kobal Presents The Top 100 Movies, which included it among works by Fellini, Kubrick, Welles, and Hitchcock. In 1999, the Library of Congress inducted it into the National Film Registry, making it “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” Today, the website They Shoot Pictures, Don’t They? ranks it as the 242nd best film of all time. (Romero’s Dawn of the Dead ranks at #335. Snyder’s remake doesn’t rank at all.) And, this Halloween, what better movie to choose than one about people trapped inside a house while ghouls prowl around outside, looking for good things to eat?