Tchoupitoulas opens with pre-teen William Zanders telling us about a dream he had the night before in which he grew up to be an NFL player, a lawyer, and an architect. At such a young age, William is clearly a hopeless romantic already (“Girls like men that have feelings,” he’ll explain later on), and that makes it equally obvious that he’ll be susceptible to the excitement of the big city lights when he and his two brothers take a trip to New Orleans for the night.

Tchoupitoulas follows them on their journey, which does not disappoint: “This is everything I hoped for,” William says when he gets to New Orleans’ French Quarter, “naked pictures, clubs….”

In accordance with these preoccupations, directors Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross cast their lens on New Orleans’ sinful side. While using a verité style to document the Zanders’ night out—a handheld camera offers unobtrusive companionship on the brothers’ adventures through the city—the doc also features some quite obvious narrative tampering: the siblings’ journey through the New Orleans streets is intercut with behind-the-scenes footage of the concert halls and strip clubs that all three peer into with fascination.

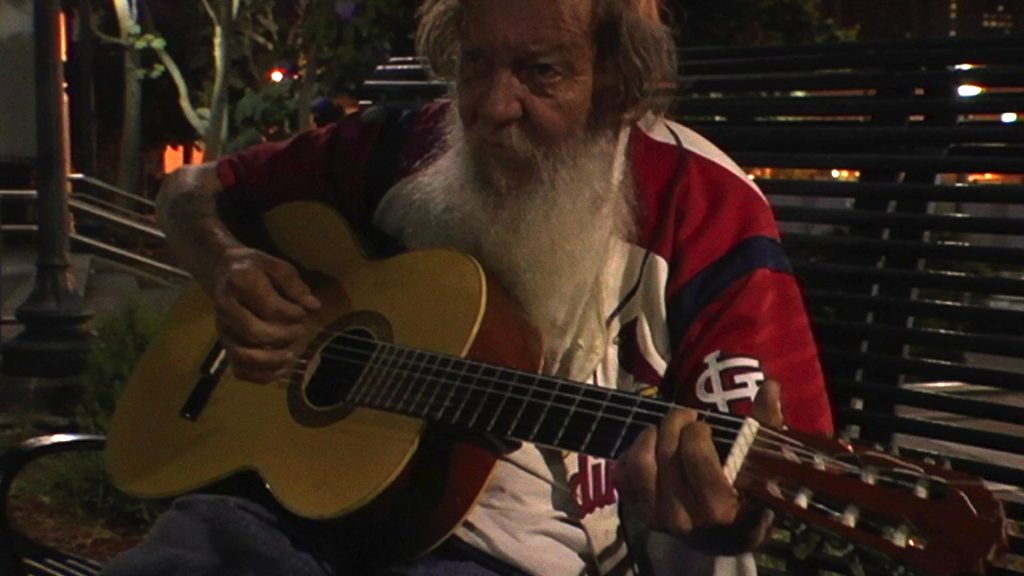

On the one hand, the combination fills out the movie’s vision of New Orleans; the exhausted faces of musicians and dancers that we’re shown help silently draw the line between what’s performance and what’s reality. That division is not always so clear cut. On the streets, we encounter many people who seem to disregard it, with the beaded revelers, the second lines, and the floats that fill the New Orleans streets giving the city a distinct theatrical quality.

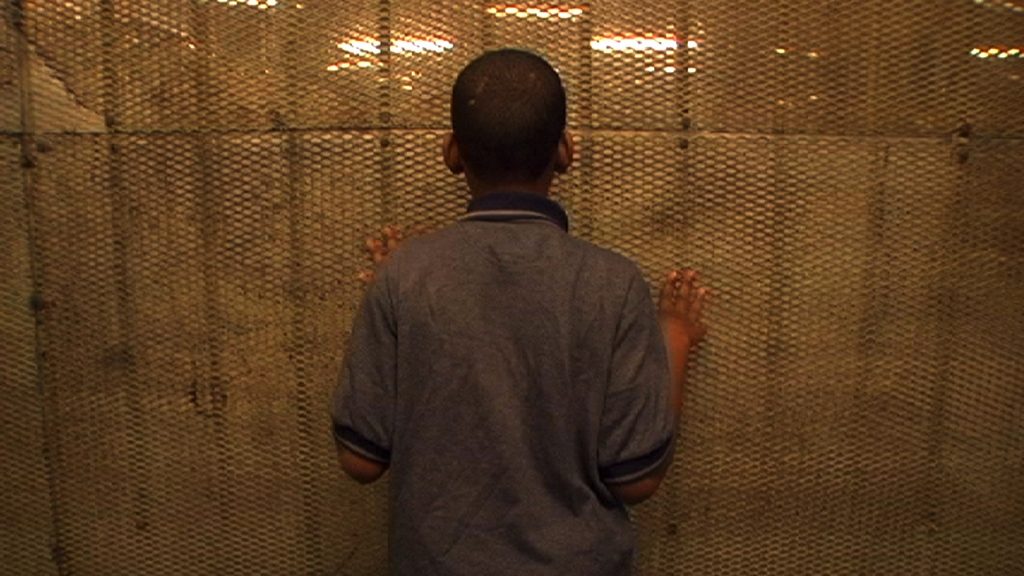

At the same time, the film’s bifurcated approach helps accentuate how the brothers’ vision of New Orleans is only half-drawn, made up, because of their ages, of sneak peeks through curtains and windowpanes. The point is not to contrast naïve childish wonder with dark realism, but rather to emphasize the doc’s predominantly fantastical sheen: the brief realist scenes allow us to better accept the otherwise dream-like tone of the film.

That style gets increasingly accentuated over time. Throughout the film, footage of the Zanders’ night in New Orleans is spliced with William’s voiceover narration. Presented over abstract compositions of blurred city streetlamps and car headlights, William’s language can sometimes seem too reflective for his young age (“Life ain’t gonna be always what it seems, so you gotta keep moving”). For the most part, though, his words show off the freeform wandering thoughts of a young boy, which help cast the film with the feel of a reverie.

The latter mood also places Tchoupitoulas in the tradition of the lyrical documentary, a classification further accentuated by the doc’s unrooted nature—although it’s set within the prescribed time frame of one New Orleans night, there’s little sense of a defined path or plot for it to take. It’s as happy to meander with the boys, to spend a moment taking in their surroundings in awestruck wonder, as it is to capture moments of sudden excitement.

And while there are Frederick Wiseman-esque attempts to create a vision of the wider world of New Orleans, ultimately Tchoupitoulas has the personal focus, rather than grand socio-political scope, that further makes comparisons to lyrical documentaries easy to make. The personal element here is not rooted in the two directors’ vision but in that of the three brothers; there’s not a sense here that the Ross’ are trying to argue that reality and fantasy can be hard to distinguish in this world. It’s only that, for the young Zanders, the line between make-believe and real life still remains blurred, if cautiously so for the older brothers.

In this respect, the film recalls Ben Rivers’s fantastic Two Years at Sea, a film far more defined by its character’s seclusion and isolation than the city-bound Tchoupitoulas, but which also blurs truth and fiction in a manner that suggests more about the protagonist’s worldview than about a director’s philosophical thesis.

The brothers’ point of view, and how much it is able to accommodate the city of New Orleans, comes to further dominate the film when the three miss the last ferry home and are forced to spend the night wandering the New Orleans streets. The event causes some anxiety, especially for William, who is the youngest. Soon, though, they resign themselves to their fate.

Ultimately, the city before dawn, populated by street cleaners rather than the drunken masses, seems more suited to the boys’ adventures. Earlier, they could only get a faint taste of the forbidden; now, the three find an abandoned ship, which they cautiously board, exploring the different rooms, freezing upon hearing any foreign sound, and ultimately running away with manic excitement.

That climactic scene captures a childishness that colors what has come before it. The brothers, we realize, are still too young for the city. The sins of grown ups may fascinate them, but it’s clear that the three don’t quite understand what they’re seeing. Their final clandestine mission better fits their age, a fact that’s obvious from the energy they display while performing it. Their view of New Orleans before was curious and awestruck, but never as engaged.

Tchoupitoulas captures both the beginnings of coming of age, particularly for William, and the nightlife of New Orleans. And at first the two seem perfectly suited for each other—the latter prepared to expand the minds of its young visitors. By the end, however, they remain distinct and, to some extent, still not quite ready to mix. After leaving the ship, while running from perceived danger, one of the brothers yells: “Today we became men!” Fortunately, that’s not entirely the case, because as William says in his narration, “this is the devil’s world,” and none of the Zanders are entirely ready for either its perils or its pleasures.

Tomas Hachard is an Associate Editor at Guernica Magazine and a film critic for NPR. His writing has also appeared in The Atlantic and The Los Angeles Review of Books.