Year 2013’s highest sci-fi concepts play on space, whether outer or terrestrial, as a void, emphasizing the isolation of any single person—even a movie star with a smile as bright as the North Star. See Tom Cruise on a lonely planet in spring’s Oblivion; Smith père and fils, currently unwelcome on Earth; or Sandra Bullock in the deep black in fall’s forthcoming Gravity.

But the cinematic frame is itself formless and void—at least in the beginning. How heavily or lightly life is inscribed upon it, once it’s exposed to light, may vary. Such a notion is the impetus for this list of both science-fiction films, and films with a science-fictional conception of negative space as an existential condition.

1. Dark Star (John Carpenter, 1974)

The astronaut is a single point in a landscape of infinite emptiness—that is, a readymade metaphor for mortal consciousness in an indifferent universe. In space, no one can hear you scream—or cry or love or ponder. The ultimate film on this theme is probably Solaris. But there’s another way of contemplating the endlessness of outer space, one exemplified by this expanded-to-feature-length student film, a dry run for Carpenter’s comically resourceful genre films, and co-writer Dan O’Bannon’s intergalactic haunted-house slasher flick Alien.

Dark Star’s perspective on human inconsequence and the vastness of space is probably a function of its budget: by necessity, we spend more time in cramped sets than with the knowingly shoestring special effects than on slapstick downtime on cramped sets. Setting aside a mid-film cat-and-mouse setpiece featuring the cheapest-looking alien in the history of cinema (the semi-famed “beachball with claws”), the basic philosophical premise of Dark Star is as follows: Space is so big that, even when you’re traveling at the speed of light, there’s a whole lifespan of spacetime between the points when anything actually happens. In Dark Star, bored, benumbed, bearded spacemen sigh indifferently into the stale air of their falling-apart spacecraft, letting the ship’s computer do all the work, the better to engage nonstop in spectacularly low-energy bickering and cabin-feverish reveries. Decades into their mission (a desultory, mostly random search-and-destroy targeting “unstable planets”), they’re starting to forget their own names; the climactic act of Cartesian defiance is left to their payload of sentient thermostellar bombs. It’s like Waiting for Godot in space, and ends so fittingly, with a demonstration of the principle of inertia.

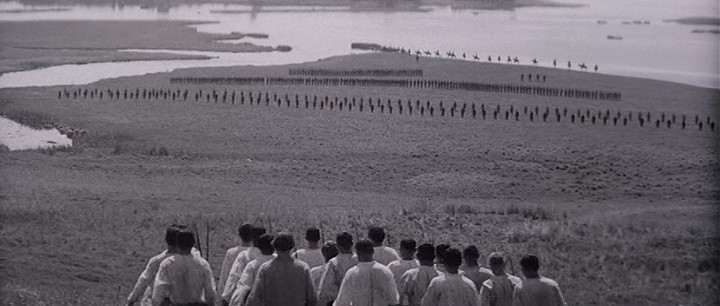

2. The Red and the White(Miklós Jancsó, 1968)

The theater of war as Brechtian bare stage. Nominally a politically safe restaging of Hungarian involvement on the Bolshevik side in the Russian Civil War, the film is really a showcase for Jancsó’s technique, and a godlike-imperious way of showing how war is dehumanizing. It’s almost a cliché at this point to describe his long takes as “balletic,” but the term is so appropriate here: the camera tracks sinuously across depopulated battlefields, as, within a single shot, multiple potential protagonists enter the frame for blank-faced solos. Every man dies alone, indeed.

3. Go West (Buster Keaton, 1925)

Westerns often treat the Wild West as a canvas for the hero to write upon: Manifest Destiny, and all that. It’s there in the spiritual affinities that John Ford is able to draw out of Monument Valley and the determined set of John Wayne’s face.

Buster Keaton’s equally famed face, in contrast, is a fathomless mask of passive endurance: even when a card cheat draws on him in this Western riff, he maintains the same faintly concerned, faintly startled expression with which his sap-head characters meet everything else the world has in store for them. Here, he plays a character named “Friendless,” who, buffeted to oblivion by New York City street traffic, decides to heed the call of Horace Greeley and sets out for wide open spaces and the prospect of self-determination.

Shooting much of the film on location in the blistering Arizona desert, Keaton finds a suitably momentous horizon-as-destiny to contemplate from the saddle of a horse—though the saddle, and the rider, are flat on the ground, having slid off the back of the horse. Even after Friendless finds work as a cowboy, Keaton never swaps out his trademark flat boater hat for a Stetson; his set pieces, as in so many of his features—particularly Steamboat Bill, Jr.—are slapstick variations on a greenhorn’s incompetence at manly tasks. Horses spook him instead of the other way around; he has trouble fishing his tiny Lady Derringer out of his massive holster.

A hapless rube in an indifferent desert landscape, Keaton takes his indignities in stride even as he falls down, repeatedly, but the situation develops some pathos once Friendless befriends Brown Eyes, a cow (trained by Keaton for the role). Like a pet dog, she follows him around the sandy, sun-blasted expanses, and the sight gag domesticates the setting. To save his only friend from the slaughterhouse, Friendless departs on an extended cattle drive as pratfall, complete with genre signifiers: a train robbery, attempted rustling, and, climactically, a running of the bulls through contemporary Los Angeles, echoing a similar urban stampede in the same year’s Seven Chances.

4. The Bothersome Man (Jens Lien, 2006)

The eternal revelation of Keaton’s onscreen persona is the pathos of underplaying. One contemporary manifestation of his influence is in the mid-aughts festival-circuit craze for deadpan comedy (surely you recall…), particularly the presentation of protagonists as absurd, apologetic augmentations to an obviously self-sufficient environment.

The titular man in this droll Norwegian allegory, Andreas, is played by Trond Fausa Aurvåg, who, with his yearning eyes and long dour face, actually bears some resemblance to Keaton. If he’s “bothersome,” it’s only in relation to the austere, cool-colored, Scandi-modern interior décor and business-casual wardrobes that characterize—or, rather, don’t—the nameless city where he lives and works. Lien strands Andreas in the center of his manicured compositions, and stages universal signifiers of urban isolation: Andreas eating in front of the TV in a barely furnished apartment; Andreas typing away in a characterless office. The city streets are frequently as emptied-out as Pyongyang, and as silent—the negative space is aural as well, offset by crisp sound effects. This Edward Hopper-esque portrait of a city-dwelling hermit feels, throughout, tweaked into the realm of absurdity.

The character is a mental blank slate as well: at the film’s outset, Andreas disembarks from a bus into a sub-arctic desert, to match his presumably amnesiac state; the city, then, is a kind of alternate reality, one emptied of… something, anyway. The yuppie and free spirit with whom Andreas pursues relationships are equally zombified, and the stylized affectlessness of their interactions is matched by sharp elisions in the editing. The whole life of the city seems clean, orderly, and naggingly arbitrary; modern life is portrayed as a disorientingly involuntary no-exit scenario.

5. Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

Cinema’s ultimate expression of isolation in an urban environment is of course film noir, whose foreboding visual shorthand for solitude, all streetlamp spotlights and backlot fog of film noir, has its roots in German Expressionism. The Weimar silent-film stylists, with their suggestive lights, deep shadows, extreme angles and wild décor, splashed their sets with subjective terrors, like an overwhelmed mind’s perception of the world.

A prime example is this adaptation of the national fable, the last film Murnau made in his native country. Sets are stripped-down and medieval; faces in close-up, haloed in light against naked backdrops, have the look of icon paintings. The dark corners of the frame leave plenty of room for flung shadows; for volcanic, hellish smoke; and for Muranu’s bold use of superimpositions. Mephistopheles (Emil Jannings) looms above model sets, as crazily large as the sum of all fear and desire. The screen space feels like an early, speculative, superstitious map: Here Be Monsters.

All this is only appropriate for a narrative concerned with one man’s aspiration to transcend death and insignificance. Faust is primarily an elemental moral drama: Like Job, the subject of a wager between God and the Devil, Dr. Faust is tempted by the latter with knowledge, power, eternal youth and pleasure. But also like Job, his struggle is secretly an existential one as well: divinity, personified as an angel with heart-shaped wings, remains aloof (especially compared to Jannings’s devilish face-pulling) as the Black Plague strikes, and as Faust corrupts the innocent Gretchen. Mephistopheles would seem to offer Faust not the spoils of evil, but the possibility for affirmative action. The moral of the story, and its definition of faith, is that goodness offers this as well—but the way Murnau fills the screen, or doesn’t, is strikingly evocative of a divine absence.

6. Carabosse (Lawrence Jordan, 1980)

Cut-out illustrations, tinted in a nocturnal blue, spin delicately against a black background, to the accompaniment of a piece by Erik Satie, whose compositions are about the spaces between the notes as much as the notes themselves. Even before a wandering planet emerges as the protagonist of this surrealist collage animation, the feel is sci-fi: the precariousness, as archaic illustrations change shape or fly out of orbit, of something rather than nothing.