[Editor’s note: Nathan Silver’s Soft in the Head premieres on Fandor today. We ran this piece originally in late October as his latest, Uncertain Terms, was showing in a variety of film festivals, including the Viennale.]

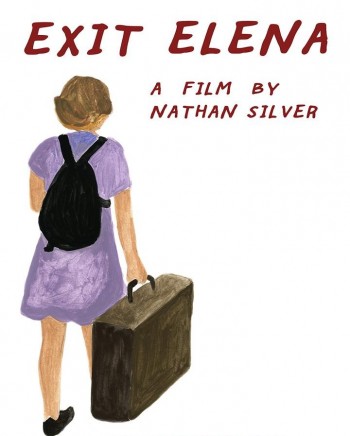

In the films of Nathan Silver, characters are constantly hurtling headlong into the unknown. Each of the thirty-year-old American director’s films have thus far featured protagonists suspended in a state of limbo, stuck between stations yet hell-bent on moving forward—though in most cases by taking a few steps back first. Even the titles of his projects—Exit Elena (2012), Soft in the Head (2013) and Uncertain Terms (2014) among them—suggest a kind of transitory or unsettled sense of existence; his latest, Stinking Heaven (currently in post production), projecting something even more intangible, an unexpected kind of purgatory perhaps. This liminal condition, however, is never quite alleviated within the confines of Silver’s narratives. In each case the central character is introduced in media res, continuing then to push on through their respective drama before arriving at a juncture of new, if equally ambiguous, concern and consequence. The end of one film, then, and the beginning of another we’ll likely never see.

At a glance, Silver seems part and parcel of a new generation of micro-budget American filmmakers preternaturally consumed by the oddities inherent in localized, everyday life. And indeed, one could easily place him amidst a spiritually akin yet otherwise disparate class of contemporaries such as Joel Potrykus, Charles Poekel, Josh and Benny Safdie, and Alex Ross Perry (all, coincidently, premiering substantial new films this year). Silver’s films, however, betray a recognizably singular kineticism, an irrepressible energy that careens forth from his characters, who externalize in words and actions feelings they can’t quite reconcile, and whose behavior is often times then transferred between their respective object of interest/desire/obsession until the self-contained worlds in which they reside can no longer accommodate anything so much as rational thought. And yet even while trafficking in the emotionally erratic, Silver’s filmography is surprisingly uniform in presentation: Each film, created in collaboration with family and friends, runs almost exactly seventy minutes in length and is formulated around a similar narrative conceit, with an outside force infiltrating a small, volatile community—even the credit sequences utilize the same yellow typeface.

The friction between these structuring devices and the mercurial nature of Silver’s narratives finds further articulation in the aesthetic constitution of his films, tightly framed yet fleetly edited into recognizably dynamic dioramas. When we first meet our eponymous heroine in Exit Elena, she’s finalizing her apprenticeship to become a certified nurse’s assistant, and soon she’s accepted her first job, as a live-in caretaker for the ailing mother of a middle-aged suburban couple. Shot with an unembellished, handheld immediacy, in a manner that initially belies Elena’s internalized self-reckoning, the film is at once Silver’s most deceptively modest and compassionate work. At times evincing an almost documentary-like intimacy, Exit Elena bears witness to a young woman—from whom we otherwise don’t glean too much personal information—purposefully placing herself in situations as dubious as they are potentially illuminating in an effort to construct a newly autonomous identity apart from whatever may have led her to this point in her life. As played by Kia Davis (who also co-wrote the script with Silver), Elena is a modest, self-consciously average young adult who nonetheless wants more out of her prescribed existence, even if she has to continue to leave everything behind in search of it.

Such restlessness is a hallmark of Silver’s characters. Soft in the Head is thus as appropriately temperamental as one might expect, and as a title not an inaccurate description of not only this film’s protagonist, but the majority of Silver’s creations. Natalia (Sheila Etxeberría) also seems to be searching for something not immediately evident in her life, but in contrast to Elena’s proactive steps toward maturation, she’s looking in all the wrong places—namely, in dead-end relationships and the bottom of the closest liquor bottle. Temporarily leaving behind her abusive boyfriend, Natalia belligerently crashes a family gathering hosted by her friend Hannah (Melanie J. Scheiner) before spending the night on the streets of New York City, where she’s quickly taken in by the benevolent if slightly sinister seeming Maury (Ed Ryan), a gentleman who houses homeless and hard-bitten citizens in his nearby apartment. Natalia’s energy, sloppy but endearing, is both stimulating and disruptive in this exclusively male context, an effect echoed in her complicated relationship with Hannah’s brother, Nathan (Carl Kranz), who misreads Natalia’s offhand sexuality as genuinely passionate advances. No one knows quite how to respond to Natalia’s presence and the inability for her to properly account for her own actions pushes the film towards inevitably tragic ends.

Among its many attributes, Soft in the Head, also co-written by Davis and frequent editor and director of photography Cody Stokes, confirmed Silver’s latent interest in the psychology of the female mind, which Exit Elena certainly suggested and which the director’s latest, Uncertain Terms, once and for all solidifies. Set in a remote upstate home for unwed, pregnant teen mothers, the film again centers on an occasionally acknowledged but underrepresented, at least cinematically, community of individuals who have arrived at an indeterminate phase of life. The outside element disrupting the established order this time comes in the form of Robbie (David Dahlbom), separated from his wife and brought to the facility as a handyman as he weighs the implications of an impending divorce. As one might expect, Silver stages the ensuing drama like a battlefield of hormones and misplaced emotions, complicating the already unstable female dynamic with an equally irrational dose of masculinity. As in all his work, impulsive action produces equal and opposite reactions which Silver’s narrative can eventually no longer sustain. And in that sense, the film’s final line—“Can we go home now?”—is one both slyly rhetorical in the context of the narrative and ironically symbolic of Silver’s greater methodology, which is both collaborative and unapologetically self-reflexive in spirit.

In fact, Silver—and, by extension, the Silver family—is present in all his work, whether literally or figuratively. The director has small, self-deprecating roles in both Exit Elena and Uncertain Terms. In the former he plays the graceless yet aggressive son of Elena’s employers, while taking on the role of an insensitive cousin and confidant of Robbie in the latter (in which he can also be heard as himself in an early scene discussing his films in a radio interview). And while he’s not physically present in Soft in the Head, he may as well be: As an obvious stand-in for the director, the Nathan character is a quintessentially Jewish suitor for Natalia, and one who he seems to delight in placing in an array of awkward romantic situations. Silver’s mother, Cindy, is likewise featured in all her son’s films, with significant roles as the mother in Exit Elena and the matron of the house in Uncertain Terms. It’s a communal/familial approach to filmmaking that’s reminiscent of probably Silver’s most direct antecedent, John Cassavetes, and one which further lends his films not only a personal but coherent identity of their own. Amidst all the fight-or-flight energy of his narratives, it’s this collaborative integrity which grounds Silver’s filmography, and yet one that continues to push him, like his characters, into an unknown yet urgent future, rife with possibility.