A car moves through a city at night, its headlights illuminating old haunts, while a smooth-voiced radio announcer accompanies its journey. “Tonight, we dedicate our show to the Latin American revolutionary folklore,” the voice says, seemingly addressing itself to the whole of São Paulo lying before the car. It makes reference to a mythical-seeming time of national pride, when Brazil was still seeking its identity. The voice then says that, while some may see Brazil as distinct from the rest of Latin America, the voice says that “History shows us the opposite: We are also part of this Latin issue.”

The “Latin issue” under discussion in Michael Wahrmann’s debut feature, Avanti Popolo, which begins with this scene, is dictatorship and its popular resistance. Like many other Central and South American countries, Brazil’s 20th century contained a period of right-wing dictatorship, engineered with the CIA’s help. On April 1, 1964, the Brazilian military deposed the liberal reform and foreign independence-minded President João Goulart, and then stayed in power for 21 years subsequently. During that time, expressions of public resistance to the government were rare, to the point where recent history was suppressed and buried. Eduardo Coutinho’s 1984 documentary Twenty Years Later gives a poetic metaphor for the public memory of the period, providing filmed images from before and towards the end of the dictatorship, and then relying on people’s oral histories to testify to the lost space in between.

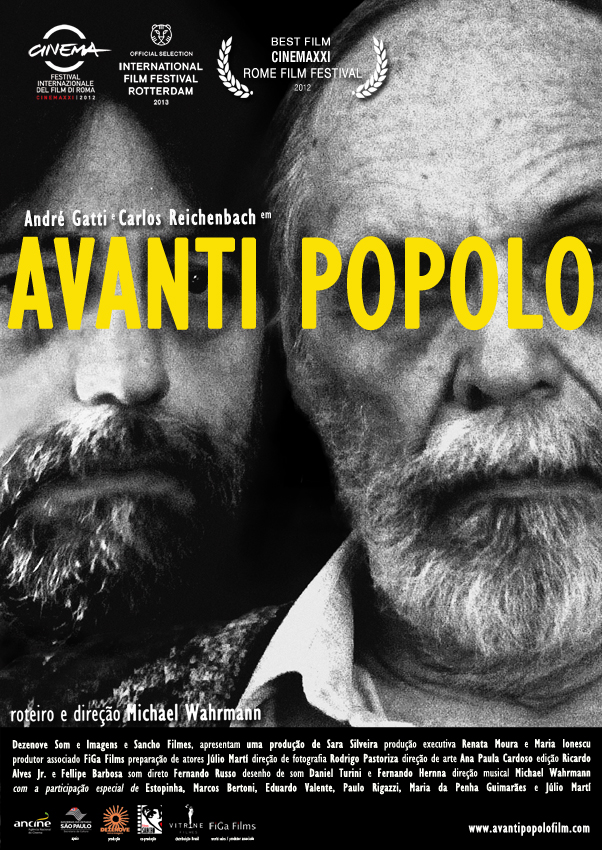

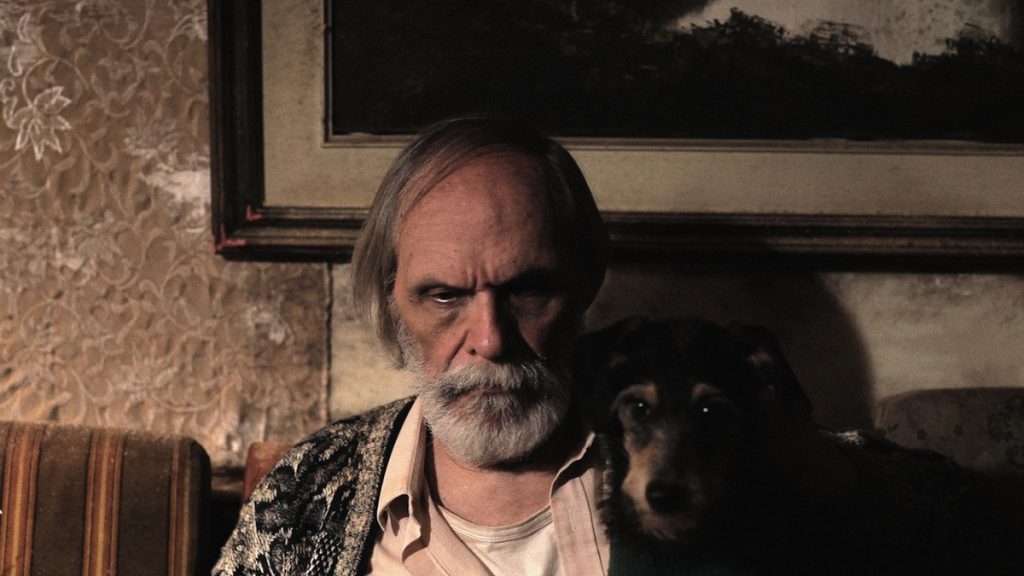

Avanti Popolo—which will be making its North American premiere with Wahrmann in person on Saturday and Sunday as the lone Brazilian selection in Latinbeat, the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s annual panorama of new Central and South American films—supplies its own metaphor for the lasting impact of the dictatorship through a broken family unit. The opening car’s passenger is the disheveled, middle-aged André (played by André Gatti), who is moving back in with his father in the wake of his divorce. The widowed father himself (played by Carlos Reichenbach), eternally accompanied by a little dog named Baleia (the Portuguese word for “whale”), exists within a kind of frozen time. His dark, disheveled living room on whose couch André sleeps stands beneath a boarded-up room that once belonged to André’s brother, who traveled to Russia in the mid-1970s and never returned. Over the course of the film Baleia, too, will go missing, sending the father out to wander beyond the house’s white gate. Meanwhile, André comes across a supply of old Super-8 films, and views the silent, late 1960s-to-early 1970s images of his united family members relaxing outdoors together while relying on his memory to fill in dates and names.

The thirty-four-year-old Wahrmann made two short films before Avanti Popolo, called Grandmothers (2009) and Oma (2011). In both shorts, young people (a small boy in the first, and Wahrmann himself in the second) ask their grandparents about their memories of the past; similarly, Wahrmann’s first feature presents an older generation’s memories of the past being left up to their descendants’ care. By giving historical context to these intimate, personal Super-8 images—which stand in contrast to the static distance from which the present day is filmed—Avanti Popolo looks to dig up a buried period. Public memory of the Brazilian military dictatorship remains obscured, even in Brazil today. What exists of it (as with many other aspects of Brazil’s complicated culture) is an opaque mixture of people and historical circumstances whose nuances must be excavated. Part of why this is so is that many primary records from the dictatorship period are still sealed off from public consumption. Brazil’s National Truth Commission, responsible for judging the dictatorship’s crimes, was only approved by the country’s government in late 2011, and the process of opening the dictatorship’s long-suppressed archives is ongoing.

Avanti Popolo’s casting of Carlos Reichenbach, a beloved cult figure of Brazilian cinema known popularly as “Carlão,” serves as a metaphor for opening memory’s archives. Reichenbach worked as part of a loose network of underground artists who have since collectively come to be known as Cinema Marginal, and whose films were often gleefully sexual, violent, and irrational. From his early work, including as cinematographer on João Silvério Trevisan’s amazing film-long howl of pain Orgy or: The Man Who Gave Birth (1970) onwards, Reichenbach was key to the movement as a cameraman, director, organizer, and teacher.

In real life, Reichenbach (who passed away last year at age 67) was a voluble talker and sharer, even hosting a regular São Paulo screening series of grungy bootlegged films from his private collection. By contrast, Avanti Popolo draws him inward and shuts his mouth. The task of recovering the history that he suggests is left to younger people.

Keyframe: Avanti Popolo feels autobiographical. What’s your life story?

Michael Wahrmann: OK. That’s pretty short. I was born in Uruguay. My parents separated, and when I was six years old my mother, her husband, and I moved to Israel. I grew up there, did my Army service as a sailor for three years, and then went to art school in Jerusalem. Then I went on a student exchange program to São Paulo nine years ago and never returned. My father still lives in Uruguay and my mother still lives in Israel, and I am far away from everybody. And regarding the film, well, I have an uncle who went to study in the former Soviet Union and never came back, but that’s another story.

Keyframe: We’re approaching 50 years since the coup d’etat that began Brazil’s military dictatorship. What do you think of modern-day Brazil’s relationship with this period?

Wahrmann: If you look through the history of Brazilian cinema, you won’t see many fiction films that deal with memory. You have lots of documentaries that deal with memory, because maybe the issue is more accessible in that form. But memories or collective traumas are not a real national issue. Brazilians don’t really like to talk about their past traumas. Brazil, as a country, has a problem with doing so, and Brazilian cinema lacks in dealing with it.

The other day I was talking to André Gatti, who is a Brazilian film historian, and he was telling me about EmbraFilme, the former Brazilian state-funded body for film production. Embrafilme was created in 1969 by the dictatorship government, in conjunction with the cinema class of the period, dominated by the Cinema Novo filmmakers and in a way, supported by and supporting them. In Brazil the cultural elite, especially in Rio de Janeiro, made peace with the dictatorship midway through its reign. They didn’t keep fighting until the end, like in other dictatorship-ruled countries; there was a moment of reconciliation. Embrafilme then financed Brazilian films all throughout the 1970s. And when I thought about this, I understood that maybe this was a reason why Brazilian cinema has not historically held a directly oppositional stance in treating the dictatorship period. The filmmakers—not all of them, but the majority— reconciled with the regime, unlike Argentina, in Uruguay, and in Chile, where the opposition was persecuted and fought until the end. In films from those countries, the wounds of dictatorship are always present, even if they are not openly discussed. Brazilian cinema slips away more, treating the problem as something from the past, rather than as a permanent issue.

So Avanti Popolo is an effort to rewatch the memory of the trauma from the dictatorship, as well as the memory of Brazilian cinema’s relationship with the dictatorship. We have Carlos Reichenbach and André Gatti together in the film discussing memory as a way to represent those points.

Keyframe: Why Reichenbach?

Wahrmann: In 2010 I was at the Amiens Film Festival with my first short film, Grandmothers (2009). He was being honored, and I saw that he looked like André Gatti, who was the first actor that I had cast. Gatti was my teacher in film school, and an amazing character. Very anti-heroic. Cross-eyed. A very bitter and frustrated person. I wanted to bring Gatti’s frustration, his bitterness with Brazilian cinema to the film and to the character of the son returning home to a missing brother and to a father who doesn’t give him attention.

I didn’t want to work with a professional actor opposite him, but I needed someone who had something to do with cinema because it would make my life easier. Carlão was a very important anarchist filmmaker. He came from Cinema Marginal, whose political approach was opposite to Cinema Novo’s and which never formed a good relationship with Embrafilme. By contrast, André is a Communist researcher who admires Cinema Novo. So once I had cast them, the conversation about cinema and history expanded. The son and the father were also the researcher and his object.

Keyframe: Tell me about the house.

Wahrmann: We worked on preparing the location for about a week. We had some architectural and conceptual references to early Renaissance paintings. We were working with layers of history—the idea was to show that somebody left this house forty years ago, and that the house never changed afterwards. We wanted to show all the layers of dust and sub-objects left there. At the same time, the house contains a sort of holy room that no one touches before the film’s main character arrives. The relationship of André with this room is also his relationship with his father, and the father’s relationship with the past. The room reflects the dialogue that the film is opening by showing light getting in.

This room contains a window. What is the window into the film? Is it our point of view, which is frontal? Is it the son’s point of view, which is inside the Super-8 memory footage that invades this room? The whole film exists inside the room, and all the layers of the film are condensed within this consistent wide-angle picture. It reflects a sort of paralyzed time, which only changes when something changes inside it or when an intruder arrives.

Keyframe: How did you find the Super-8 footage?

Wahrmann: My first short, Grandmothers, was shot on Super-8. I was not a Super-8 filmmaker before then, and then suddenly I began going to lots of Super-8 film festivals. I met a great Brazilian filmmaker named Danilo Carvalho who made a short film called Supermemórias (2010) out of Super-8 footage that he collected in Fortaleza from people who gave him their home movies. (In fact, most of the material in Avanti Popolo comes from Danilo; other material comes from Marcos Bertoni, an actor in the film and a true Super-8 researcher, and some material we shot ourselves.) I was working on my screenplay, and when I saw those images I thought that I might be able to re-appropriate this footage within a fictional story.

When I use documentary Super-8 footage, I am creating a valley between someone’s family material and my own material as a viewer. It could be my stuff—I don’t know to whom this footage belongs. Maybe somebody in Fortaleza will see the film and say, ‘Oh, that’s my film.’ It’s his history, as well as ours. The Super-8 footage is a way to connect private stories to more national issues. It makes clear what we’re talking about. The images of happy families change throughout the film until we end up with a lonely brother in Russia. This footage tells the story of Brazil by reminding us of something that we have forgotten or still have in mind.

The Super-8 also functions formally as a way to stitch the film’s other scenes together. I didn’t want to cut the film, so this way I could stop sequences and then continue them later, and in between bring a bit of sentiment into a very cold and distant picture. The shooting format we chose is distant from the spectator, and sometimes a bit of nostalgic sentiment was needed to bring viewers closer.

Keyframe: Why that distance?

Wahrmann: There is something about films that makes me nervous—when stories have heroes, and when I identify with the heroes but not with their stories. The moment that I can empathize too much with a character, I forget my own history. I forget about the big story and focus on the little man. That’s why this film is always frontal and distant—because my point of view as a spectator and as a director are the same. It’s not a sentimental point of view, but rather one for analysis and for criticism. I let you observe the story without letting you get inside it, which hopefully lets you think about what I am trying to tell you. Because the moment you get involved too much, you don’t think anymore. You love, and love makes you blind.

So I didn’t want the film to become a particular story, but a general story, a bit like what happens in Aki Kaurismäki’s films. You don’t get involved emotionally in those cases, which is also related to humor. Aki Kaurismäki walks parody. In my case, all of my films are funny. People ask me, “What kind of film is Avanti Popolo?” to which I say, “Oh, it’s a musical parody about the Brazilian dictatorship.” (Which is not far from the truth.) I met this French producer who said, “Well, there are no gods in the film. You kill them all. The Communists, the little dogs, the old people, the young people.” I think that Aki Kaurismäki does something very similar with his characters. He likes them, he is close to them, but he doesn’t make them heroes. There are no sacred characters in his films—everybody has something twisted about them. You cannot love his characters. You can understand them, you can get close to them, but you can’t feel bad for them. You feel bad because of the story, but not for the people in it.

David Perlov is another important filmmaker to me in this regard. Similarly, with Perlov’s films, you don’t get involved emotionally. He opens his Diary (1973-1983) saying, “Professional cinema does not interest me anymore.” Then he puts the camera in the window of his building and shoots an epic that is also intimate. This relationship between epic and intimate, achieved while using the minimum that you need to tell a story, interests me. I made two short films called Oma (2011) and Grandmothers, which are both very autobiographical, very intimate, and made with very low resources. Avanti Popolo contains thirty-two shots filmed over six days. It tells a simple, intimate story. But it’s also an epic story. David Perlov joins his own personal story with his nation’s history, and they come to remark ironically on each other. That’s what I like in cinema. You are constantly analyzing the image and the speech, and you don’t forget yourself. It’s not an escape—it’s a confrontation.

Keyframe: How did you find your film’s title?

Wahrmann: Like many things in the film, the title has some layers of representation. But it begins with a very simple issue, which is: I like the way it sounds. Avanti Popolo! That’s a great name for a film. It’s inspirational, it’s a moving title, it’s action! And it’s the total opposite of what’s onscreen.

Avanti Popolo in Italian means Go Forward People. And in my film, nobody goes forward. We meet two lonely men who are stuck in history and don’t go anywhere. The key for the film is the abyss between the past and the future of history and of the characters. This title is the name of a revolutionary anthem that represents long-gone ideals. It represents a movement that is defeated and lonely, like the characters of the film. The radio broadcaster sings this anthem alone while we see a ruined cinema theatre. This broadcaster, we later find out, is also the director of the film—me.

There is also another film named Avanti Popolo, an Israeli film from 1986 directed by Rafi Bukai. The broadcaster in my Avanti Popolo mentions the earlier film. I love this other Avanti Popolo and think that the name in both films comes for similar reasons. Bukai’s Avanti dialogues with my teenage world as a political activist in Israel. (My teenage dreams were to be a politician, to make a revolution, to join a guerrilla group, and then I got frustrated, gave up, and ended up making films.) It was a great inspiration back then, a film that actually made people move and think about revolutions. It was a hard poem about war and the Israel-Palestine conflict. It’s still a punch in the stomach that hurts and defeats you. But at the same time, it’s a film that gives you hope. It believes in human kindness. My Avanti doesn’t have this way out. It’s not a humanist film like Bukai’s. And in a way, this difference creates a dialogue between the Avantis. It’s an homage to my childhood heroes, but with a pessimistic look at them. My Avanti is not hopeful like Bukai’s Avanti. It’s a post-mortem film.

Keyframe: In Uruguay there was also a dictatorship. What are the major differences that you see between the way that Uruguay has dealt with its legacy and the way that Brazil has?

Wahrmann: Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile all deal obsessively with traumatic memories, as does Israel. I have discussed these traumas many times with people when I have been in Uruguay and in Israel. My two short films even deal with the Holocaust. But I don’t see these national obsessions as problems. On the other hand, in Brazil the discussion about traumatic memories is not very developed—the dictatorship is from the past, we talked about it, we solved it, and we should go on. But things are actually not solved. In Uruguay and in Argentina a Truth Commission formed much earlier than in Brazil. Generals were tried and placed in jail earlier in those countries than they were in Brazil. In Brazil, when the current President Dilma Rousseff [a guerrilla fighter during the dictatorship] was running for office, a congressman accused her of lying to the police during the dictatorship while she was in prison being tortured. He said that he could not vote for her as a result. This was an acceptable public attitude, and the lack of memory in this bothers me.

But even though I am concerned about preserving memory, I did not want Avanti Popolo to be a film of mystification. It’s not about those heroes from the dictatorship. It demystifies the whole utopian revolutionary thing. It’s critical of utopias. In Uruguay and in Argentina, the film has been well-accepted for being ambiguous. I’m curious to see how Brazilians will accept it.

Keyframe: What do you think of Brazil’s recent protests? How do you believe that they relate to Avanti Popolo?

Wahrmann: Avanti Popolo is a film about endings: The ends of ideologies, of utopias, of cinema, of hope. These endings relate to beginnings: The post-Cold War world, the Internet era, the rise of brutal liberal, capitalist markets, and life in which the ideals to which I’ve referred have already lost their struggles. Even the new socialist governments around the world, which might have represented a last hope, have mostly disappointed with the ways in which they do and don’t balance their own power with attention to social issues. (Although in their way, they are still a last hope.)

We can see this very clearly through Brazil’s recent protests. I am in favor of popular protest, and I believe that popular opposition is always a blessing for any country and for democracy in general. But I have the feeling that it’s all empty in this case. There is no real alternative program. The goals of these protests seem to be more virtual than real. We want better health!—Yes, of course, everybody wants that. We want better transportation!—Yes, naturally, I don’t know anybody who likes being stuck on old, crowded buses during traffic. We are against all politicians! They are all corrupt!—This thought is the basis for dictatorship. When you’re fed up with politicians, you need one strong man to clean up their mess. Popular protests that lack a strong ideological basis are dangerous. Throughout history, they have led to authoritarian governments, or to ineffectual liberal groups like Brazil’s Green Party, which counts on our empty ideological decade (I mean, who is really against clean air and water?) to disguise how it is backed by industry as much as any other political party is.

After several weeks of demonstrations, we have gotten some issues resolved. The price of bus fare will not rise for the moment. The government has declared that it will be more committed to health and to education. We were given a popular plebiscite for political reform that it seems like most people (including me) don’t really understand, but which we should nonetheless believe is a victory for democracy. My sense is that the wrong issues are being discussed while the real ones are ignored. For instance, the Brazilian minimum wage was not discussed much publicly during the protests. This wage is around $300 U.S.; a Big Mac in Brazil costs about $6 U.S. (which makes it one of the most expensive Big Macs in the world). This issue is the basis of transportation, health, and education problems, but it’s not being talked about. There is a famous Brazilian song that says, “The favela is not a marginal stronghold, the favela is a social problem.” The way that the favela is mostly treated in recent Brazilian cinema and society is similar to how the most important social issues were treated in the protests. They were ignored.

What actually united the protests to begin with was police brutality. Where does that come from? Don’t tell me that this attitude has nothing to do with Brazilian history. But why should we talk about the past? After all, it’s the past, right?

So I see lots of facades with very little substance, a bit like the slogans in George Orwell’s book 1984—’War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.”’The most significant achievement of the past few weeks, which I don’t think was at all the intent of the protests, had been a loss of support for Dilma, Lula, and the Worker’s Party. Brazil might be moving towards a right-wing government, and while democracy legitimizes such a scary proposition, I much prefer what we have now. Fernando Collar, the former Brazilian President who lost his office due to impeachment, recently published an article in which he ironically said: ‘In 1992, they asked for the dismissal of the President. Now the demands are numerous, generic, and diffuse.’ I agree with him, and I feel that when the demands are so generic and diffuse, the wrong people can take advantage of them. This scares me. Avanti Popolo reflects my fear, as well as my sense of hopelessness with the current situation. Like my characters, I feel blind. I see no ideals left to hang onto. We need to restart.

Keyframe: How do you see Avanti Popolo as evolving from your earlier work?

Wahrmann: Formally, Avanti Popolo is the opposite of my earlier films. My first shorts were made on Handi-Cam, with lots of fast cuts. They were very shaky. And this film is filled with steady long shots. I wanted to try the other formal extreme. But at essence they are the same film. In Grandmothers a child cannot change his socks and underwear because his grandparents were in Auschwitz. In Oma, my grandmother speaks in German all the time, even though she’s living in Uruguay. In Avanti Popolo, the main character sleeps on the sofa because his brother disappeared. The films all deal with historical traumas by relating to very little things. Their immediate situations are always very small. None of the people in the three films are seen with admiration, and their memories are always treated with criticism and conflict. The child in Grandmothers challenges his grandparents’ memories, as I do in Oma with my grandmother’s memories and as Gatti in Avanti Popolo questions his father’s.

At the same time, the films see those memories as necessary. I’m not sure whether remembering or forgetting is the right approach. There is something very healthy in just leaving traumas behind and going on. There is also something very unhealthy in doing that. The Israeli writer Amos Oz said in an interview, ‘We must forget, but without forgetting the forgotten.’ This strange, ambiguous sentence is important for all my films. My goal is not to make films—cinema is just a tool to talk about the things that bother me. So yes, we have to forget and move on with our lives, but how can we?