Fred Gwynne made himself semi-famous lampooning Frankenstein’s beloved monster in TV’s The Munsters. His legacy portraying that literary character adds some poignancy to his role as “Charles Dickens” in Any Friend of Nicholas Nickleby Is a Friend of Mine. Filmed as an episode of TV’s American Playhouse, Any Friend is a Ray Bradbury story the writer himself endorsed with a bit of narration. “Dickens” lands in a nondescript part of Rockwellian America and Ralph is sensitive enough to feel the winds of change he rides (Amtrak). Ralph hopes to be a writer someday and knows just enough for Gwynne to be the real thing to him—the true and great Charles Dickens, creator of Oliver Twist and so many other emotionally intimate stories of resilient children. The adults around him are leery, but this story takes place before every public school had a school psychologist so it’s good Ralph’s grandfather has a whimsical spirit (instead of a suspicious mind). Does it have to be true to be good? Love is the in the prose, even if “Charlie” didn’t write it himself, and Bradbury is always supremely interested in the developing young writer—as an institution. If the intention is good, how could anyone do wrong?

But “Everyone is double, triple or quadruple,” which, if you’re untrusting, casts doubt on the nature of…well everyone. One can be both a social invention and a secret to others; you choose if you see that as falsehood. Charles Dickens (the man, not the reverent poseur played by Gwynne) had a secret second love, one he left his family for in the early winter of his life. Despite the way this history casts shadows on his virtue, it also implies he has a boundless and magical inner life. Beneath most stories of thrilling and dynamic writers (as in the recently released The Invisible Woman), is a lie that exists to bolster them: a necessary personal fiction that acts as a load-bearing beam in their intimate architecture. Films about writers delight in revealing the “lie that tells the truth.”

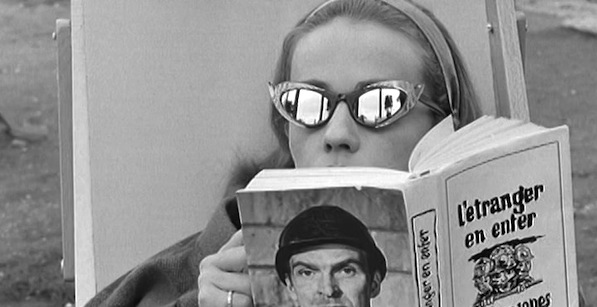

Writer of O

The writer of O relied on her pseudonym. She wouldn’t reveal her identity as a respected editor at France’s Gallimard press until 1994, four decades after publishing her elegant erotic novel. Beyond dickering about obscenity, the biggest argument The Story of O inspired was “who wrote it?” No one believed it could be a woman because the romance seemed designed for the pleasure of men. Dominique Aury (aka Pauline Reage) was in her forties when she wrote O, and in love with a philandering gentleman twenty years her senior. Intimately she scribbled the book in bed, a love letter to the man she worried she didn’t offer enough to: “ I wasn’t young, not that pretty.” In the book women chat about the sex appeal of fifty-year-old menfolk and what sense it is they love thirty-year-old women. These dialogues punctuate episodes of sexual bondage, domination and the most literal depiction of power dynamics fit to print. As France believed the writer a man, Aury only revealed her secret to the lover who’d receive O as a valentine, the intent of which was its own power play, a bond made of bondage tales and compulsory silence.

The Getting of Wisdom

The Australians prefer defiance and so adore Laura Tweedle Rambotham, heroine of young adult novel The Getting of Wisdom. Indeed the book by Henry Handel Richardson (reportedly a pseudonym for a female novelist) has remained consistently in print since the book’s first press in 1910. Before the Academy nominated him for Tender Mercies and Driving Miss Daisy Bruce Beresford directed this icon of feminine larrikinism, and his direction feels like it’s trying to live up to the honor. Susannah Fowle plays the cheeky young Laura, toughing-out the cruelties of fickle peers as she finds ways to also earn their respect. Her provincial mother toils to put her obviously gifted girl through the best education and the best education is indeed a hunting ground, so outfitting her with garish dresses becomes another way she inadvertently paints a bulls-eye on her kid. But Laura is cunning, and she captures the imagination of her class with an affair she fabricates with the young married minister. Comically it seems there’s no way to talk about the man that isn’t a lie. It’s tough from every angle and everyone (teachers included) strives to make it harder, which only throws into relief what makes this Aussie defiance so inspiring: to buck a system made of fire and brimstone they can only fight back with handfuls of their own sparkling ash.

Hunger

Norwegians apparently see the struggles of storytellers less romantically. Henning Carlsen’s adaptation of Hunger (based on the book by Knut Hamsun) depicts the lies of its protagonist as a conspiracy of one man against himself. The writer is starving and often destitute (during winter, naturally), but is so desperately prideful he lies about his every gesture. “Be careful wrapping that, it’s got expensive vases inside.” This he says to a shopkeeper wrapping his bedspread now that he’s been turned out. A friend asks about the bundle and “It’s cloth, a man’s got to keep his appearance.” He sells an article of clothing to give change to an out-of-work shoemaker, and convince himself his airs aren’t put on; despite the fact they both sleep on the street tonight. Indeed it’s hardly hunger that’s driven him slowly, socially, mad, but sometimes the symptom appears greater than the disease.

Eva

Joe Losey’s Eva portrays sadness as a sign and glamour as the cause. Besot with ennui, an unreasonably successful Welsh novelist (Stanley Baker) has obtained all that means success to the creative class-cum-glitterati. Now what? His dolce vita is such a cross to bear. Imprisoned by his own hipness he gets to be a sympathetic figure in addition to looking like a winner and the girls love a winner. Based on the book by James Bradley Chase, the writer is jaded by the excesses of the in-crowd and now nothing has value. Yet, Jeanne Moreau out-mopes him (she’s an Olympian at that sport). She enters the writer’s orbit blithely, and proves his existential crutch was acquired on the cheap and nurtured into reality. Hers, my dear, she was born with.

Genet

Genet begins his 1981 interview with Antoine Bourseiller with an admission he expects to die soon. Genet famously eroticized the dark and masculine prisons of France before falling in love with the idea of the Middle East and settling in Greece—a place he felt so erotically charged he transferred his attraction to prison into one for a land he says pokes fun at itself and its gods. Self-awareness is such strange liberation. The patron saint of gay lit seemed to make a case his technically illegal private life was never meant for secreting. Only you may call your life “private” if you want to.

Destroy All Rational Thought

The Beats famously went to “The Dark Continent” to screw with impunity. Morrocco was a sexual/spiritual haven, a place built on mores their WASPy, capitalist nation couldn’t abide. Made with the help of surviving Beats Destroy All Rational Though homages the movement and records an Irish art show of North African inspired Beat art. Glorious black-and-white footage of Burroughs, Balch and Brion Gysin, feels like a shot in the arm in the middle of a mucky video of musicians and paintings of Tangier. I’m crazy for the beats, a group of writers, artists and musicians who hunted for some rhythm to string through everything, whether it was naturally occurring or not. Despite finding myself totally sucked into their mojo, I hate most everyone else’s expressions of love for them. Hilariously, I believe this is a shared experience. Case in point: the prized Morrocan painter the curators coddle like a prince has little patience even for Ira Cohen’s poetry reading. Who said they inspired each other? Excessive Joujouka “Magic” (read Morrocan wind music edited into cacophony) will send you into trances or make you hit fast-forward, which is pretty in tune with the works that inspired it: borne of restless disobedience, but not for all tastes.

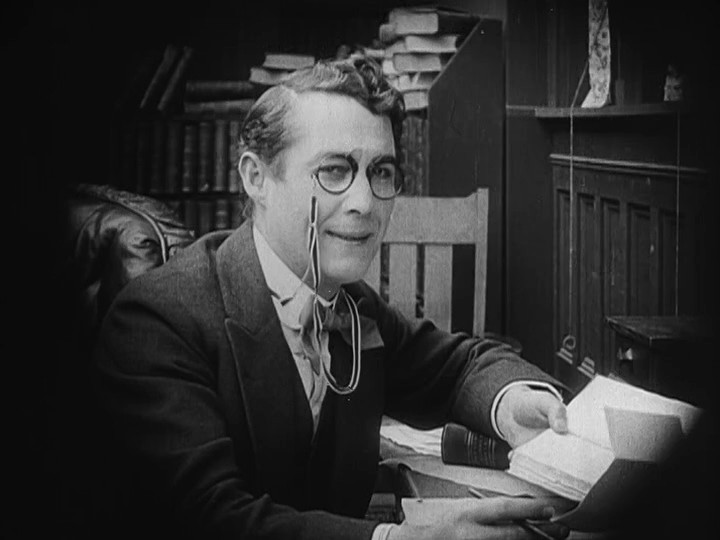

The Avenging Conscience

It’s hard to describe D.W. Griffith’s homage to Edgar Allan Poe as an adaptation…it’s more of a mash-up of basic conflicts—a laundered, Sparks Notes version of inky dread. Oh, Poe was popular enough, and doesn’t require tidying-up before further publicity, but Griffith’s The Avenging Conscience (aka Thou Shalt Not Kill) dry-cleans him anyway, justifying his characters’ guilt with Christian morality. To my tastes, what provokes about “The Telltale Heart” is how the murderer’s crime, and his realization of power, is a poison that eats him from inside. God is not his catalyst for guilt. But Griffith’s Victorian sensibility is what jives most with Poe, so the adaptation of his literary inventions are most interested in plot points. Avenging Conscience mashes Annabel Lee, Pit and the Pendulum, even a bit of Black Cat but all those references can’t recreate the feeling—then, perhaps they aren’t trying to.

Wind in Our Hair

Experimental filmmaker Lynne Sachs adapts a spirit in Wind in Our Hair. By stringing together tiny moments of tween girls playing alongside radio reports of a farmer’s strike, she suggests the girls’ motions match the union demands. “We don’t need a master, we need a leader to govern” plays over the radio and moments later we learn the weakest girl has a malady and can’t do chores; she participates in playtime by bossing—rather, managing—the others. Inspired by the work of Argentine writer and short story superhero Julio Cortazar, Sachs is aiming first to create the feeling of small, semi-inscribed moments that could, if you wanted, be viewed interchangeably. That “create your own adventure” style of novel was among Cortazar’s greatest inventions (for example: see his “counter-novel” Hopscotch), but of all the writers of his generation, and even all those he’s influenced, he may be the only one to inspire so many New Wave films (Godard’s Week-End and Antonioni’s Blow Up).

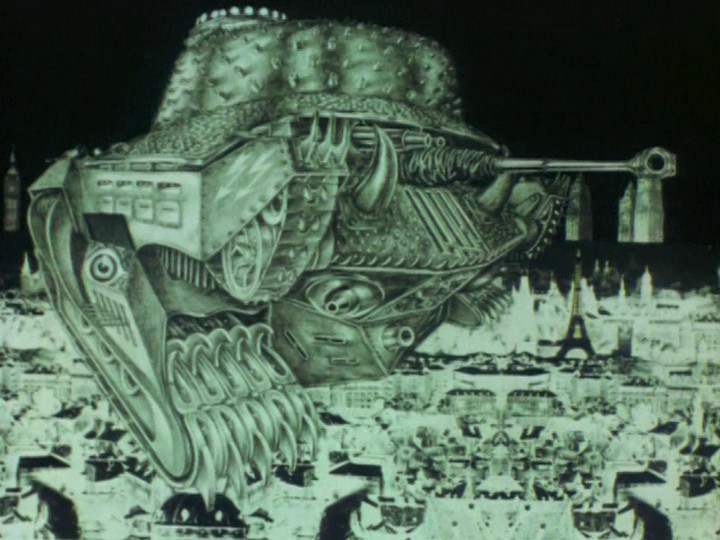

Forward March, Time!

Soviet poet/playwright Vladimir Mayakovsky was a patriotic futurist and, like Dickens, had a secret romantic life…or, rather, a romantic life that kept a secret briefly from him. On a tour of the states, Mayakovsky met Elli Jones and, years later the couple had a quiet reunion in France. This is where Elli revealed she’d produced Vladimir a daughter. He was ignorant of his half-America child while he was professing his love to another woman, publishing valentines to her that called her by name (see: A Letter to Tatiana Yakovleva). He did his own PR for that public romance. Filmmaker/animator Vladimir Tarasov animated a bombastically seventies visioning of Mayakovsky’s writing, a Cabaret—colored, funkadelic futurism full of references to his politics, and proof he may live on in memory as time marches forward: Forward March, Time!”