It’s disconcertingly easy for a film to “fall through the cracks,” failing to get a successful release initially then never quite getting “rediscovered” in later years. It’s also easy for a filmmaker’s entire body of work to go pretty much the same way, one near-miss following another until suddenly he or she is more or less done, without having ever properly “started” in terms of acclaim, monetary reward, or the guarantee of a next job.

Movies like Four in the Morning and Black Joy are good illustrations of that scenario, as is their director Anthony Simmons—not that you’d ever guess the same person had directed both, their being wildly different in almost every way. Both are distinctive products of their time that were also ill-timed in various ways, and now many decades later (nearly a half-century for Morning) might well finally get their due.

Simmons, now ninety years old (and who directed a couple shorts as recently as 2010), has worked in the U.K. film and TV industries for over six decades—yet over that span he’s remained a marginal enough figure that in 2008 the Journal of British Cinema and Television titled a long interview with him “The Outsider.” Originally expecting to be a lawyer who wrote fiction on the side, he decided instead to become a director because “if I wrote films it was more immediate….You haven’t got to spell out the words. You just make the image and tell the story.”

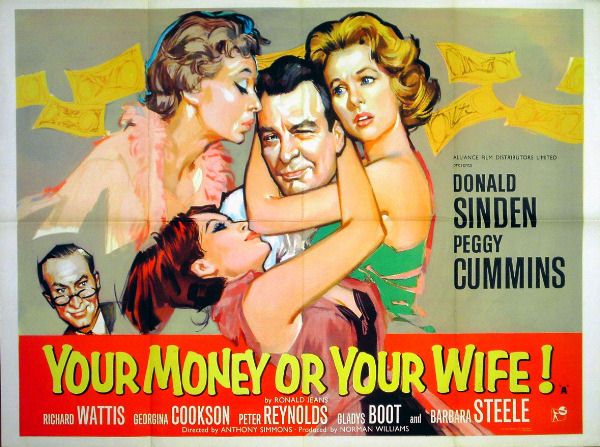

He started with a bang, winning the Grand Prix at Venice for 1951’s Sunday by the Sea, a fond, frisky non-fiction miniature capturing Londoners at play on the weekend. That and several subsequent short documentaries honed his skills while he angled toward breaking into features. At first he produced a couple directed by others (notably 1957’s Time Without Pity, one of the earlier British films made by Joseph Losey after his Hollywood blacklisting), then made his official debut with a featherweight 1960 comedy, Your Money or Your Wife.

Five years later he got off the ground a project doubtless considerably closer to his heart, this time as both writer and director. Partly developed via cast improvisation, Four in the Morning cut between three simultaneously unfolding stories, two of them involving troubled couples: First a wife at wit’s end (Judi Dench) being left alone with her squalling baby greets the husband (Norman Rodway) who’s finally crawled home in the wee hours, drunkenly dragging along his best mate (Joe Melia). A more quietly argumentative duo are Ann Lynn as a nightclub employee and Brian Phelan as the suitor she seems at first reluctant to meet with, then confesses “I think I love you.” (It’s deliberately kept ambiguous just how long, or well, they’ve known each other.) Finally, we see police taking charge of a woman’s body that’s washed ashore from the Thames—perhaps a suicide, perhaps a murder or accident victim, but surely one more person consumed by everyday despair.

Larry Pizer’s black-and-white photography captures a London well off the tourist maps, one of dingy walk-up apartments and bleak industrial landscapes. Love and happiness seem remote possibilities—these characters are all trapped in their separate ways. The most heartrending case is Dench’s wife, who begs her spouse to understand that she, too, needs to have a life outside their claustrophobic flat; but he sees staying home with the baby as “your part of the bargain.” (One expects this woman is going to seize feminism with a vengeance in a few years.)

Now of course a world-famous Oscar known most widely known for playing James Bond’s boss “M,” the future Dame was then a rising stage and TV actress whose first film brought her a British Academy Film Award for Best Newcomer. Yet Morning failed to secure a regular commercial release. It was, perhaps, too much in the bleak working-class-realism vein of earlier “Angry Young Man” films at a moment when Darling heralded the arrival of “Swinging London” onscreen. (If the characters in Simmons’ film were to do any swinging, it would by the neck, at the end of a rope.)

Similarly thwarted from finding a larger audience was Black Joy twelve years later. This very different London character study—set in a percolating Brixton culture of Afro-Caribbean emigres—was adapted from a play (by Jamal Ali), though there’s nothing stagy about the resulting film. Ben (Trevor Thomas) is a naif fresh off the boat from Guyana who quickly proves prey to various streetwise thieves and hustlers, notably slick-talking con artist Dave (Norman Beaton). But the “country boy” learns fast, turning the tables on those who’ve taken advantage of him.

Cheerfully profane, Black Joy may seem somewhat stereotypical now in its over-the-top characterizations, but “Britain’s first blaxploitation movie” (as it was rather dubiously labeled) is still infectious in its boisterous energy and warmth. It has a fantastic soundtrack of raggae, dub, soul, disco and even Burundi drumming, which apparently raced to the top of the U.K. charts. The movie, too, looked to be a big hit—until a legal dispute over music rights yanked it from cinemas soon after opening.

Simmons’ other features were also dogged by bad luck. The Optimists (1973), based on his own novel and starring Peter Sellars as a street busker, won fine reviews but was poorly handled by its distributor. 1989’s Little Sweetheart, an offbeat thriller about a criminal couple who meet their match in a bloody-minded nine-year-old girl, didn’t get distributed theatrically at all—its mix of escapist and disturbing elements deemed too commercially risky. He was hired to direct 1981’s Green Ice, a South American caper with Ryan O’Neal, but wound up cut loose in the crossfire between the stars and producers.

In the long run, he’s perhaps been most successful in television: Directing episodes of popular British series like Inspector Morse, plus the occasional TV movie. Among the latter, there was the outstanding 1979 “Play of the Week” On Giant’s Shoulders, a rigorously unsentimental fact-based drama about a poor couple who adopted a limbless boy whose birth defects were the result of disastrous morning-sickess drug thalidomide. (The boy, Terry Wiles, played himself.) It reunited Simmons with Dench—who got more BAFTA attention as another working-class wife, this one with a good heart buried well under a fingernails-on-chalkboard, battle-ax personality.

As of this writing, On Giant’s Shoulders was available in its entirety on YouTube. Not so, alas, The Day After the Fair, a 1986 BBC film that some consider one of the best Thomas Hardy adaptations ever made. Perhaps, like Black Joy and Four in the Morning, it will also slip back into public view some day, giving us another angle from which to appreciate Anthony Simmons’ oft-thwarted but stubbornly long-lasting career.