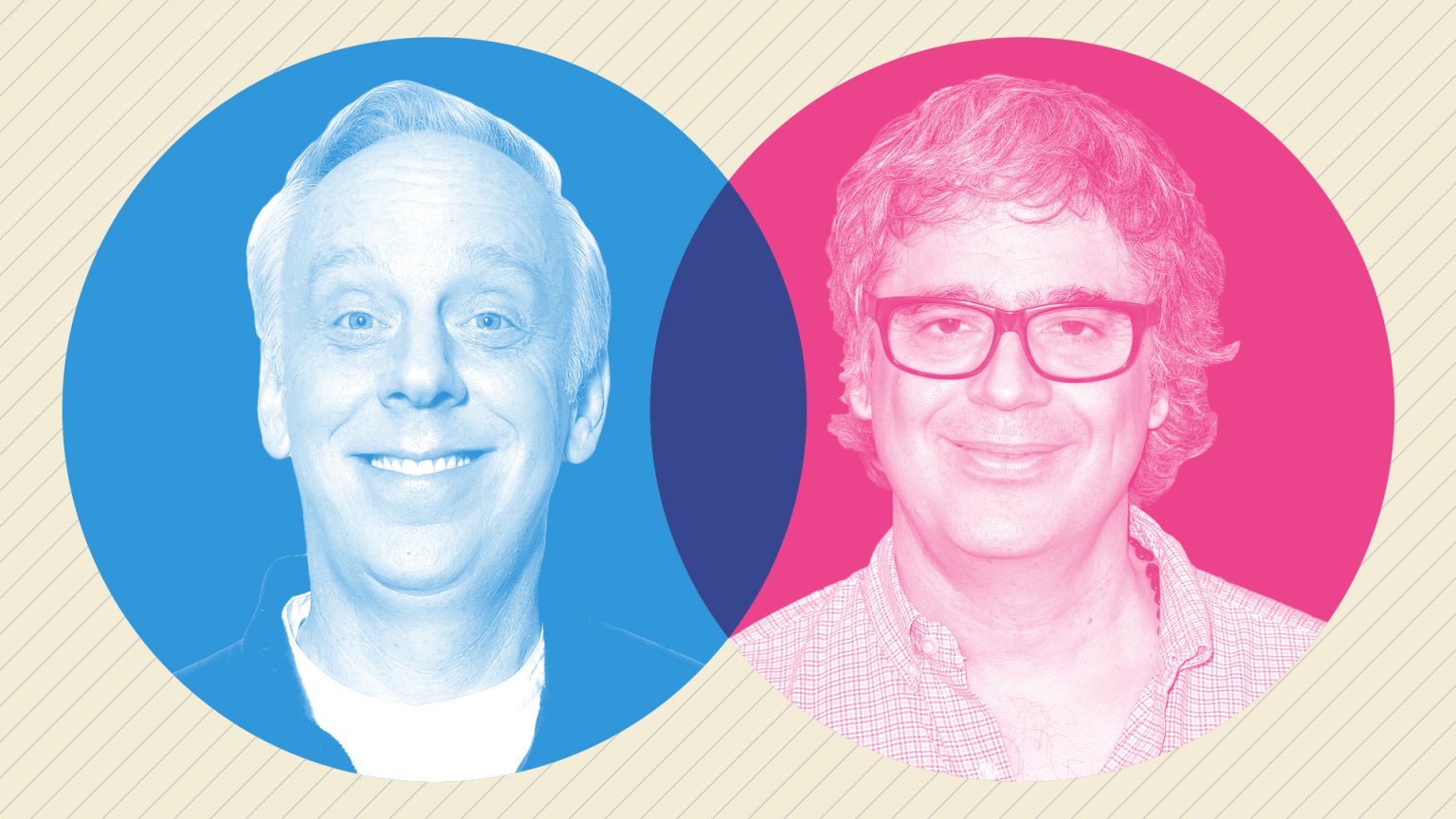

While Mike White and Miguel Arteta may not be a pairing as commonly referenced as bread and butter, coffee and cream, or Scorsese and Schrader, this screenwriter-director team has certainly proven worth keeping an eye on over the last two decades.

Their shared career hit the ground running at Sundance in 2000 with their first collaboration, Chuck & Buck, which follows Buck (also Mike White) after the death of his mother as he tries to rekindle a relationship with childhood friend Chuck (Chris Weitz). What begins as a seemingly straightforward, or even stereotypical, buddy comedy develops into a deeply moving character study—the film examines Buck’s stunted development and his inability to move past the intense relationship that he once shared with a friend who has seemingly outgrown him.

White’s performance, and the overall tone of the film, are hard to pin down: In one moment, Buck seems to be a repressed child, awkwardly sucking on lollipops and making messy photo collages for his friend. In the next, he is a creepy stalker, following Chuck and his fiancée, Carlyn (Beth Colt) across Los Angeles. He even spies on them having sex, dreaming of the days when he and Chuck would sexually experiment with each other as eleven-year-old boys. Every scene takes on nature all its own.

While this might be a weakness in many other films, it is in fact a great strength for this one. Were it to be re-cut, Chuck & Buck could easily be made into a slasher film, an intense relationship drama, or even a dim-witted comedy. White and Arteta’s impressive ability to create films that are funny, touching, and heartbreaking all at the same time is on full display in their first feature, and has remained throughout their collaborative body of work.

White and Arteta went on to make 2002’s The Good Girl, in which Justine (Jennifer Aniston), a discount store clerk frustrated with her boring, suburban Texas life, has an affair with her younger, equally pessimistic co-worker, Holden (Jake Gyllenhaal). Like Fargo before it, The Good Girl satirizes the mundane lifestyle of small-town America, introducing a multitude of quirky characters in a boring place. Whether it be Justine, her husband, Phil (John C. Reilly), or Holden, the characters in the film almost always end their days watching television. They work their boring nine-to-five jobs during the day and then watch other people, in a world far away, live out the exciting lives that they can only dream about.

When Justine and Holden finally spice up their lives and begin sleeping together, everything goes wrong. Phil’s best friend, Bubba (Tim Blake Nelson) catches them and blackmails Justine into sleeping with him too. Justine then becomes pregnant, not knowing whose baby she is carrying. And that’s only the tip of the iceberg.

While there is comedy sprinkled throughout, the film ends on a bleak note, mirroring Justine’s dour worldview. When they are first getting to know each other, Justine says to Holden, “I saw in your eyes that you hate the world. I hate it, too.” By the end of the film, Justine has to question if it’s the world she hates, or herself. After all, the world has given her a husband who loves her enough to forgive her adultery, and a child she thought she was incapable of having. She asks herself, “If I died today, what would happen to me? A hateful girl… A selfish girl… An adulteress… A liar.” The film’s subtle introduction of serious themes amongst funny characters is a testament to White’s writing, and Arteta’s precise execution of tough tonal shifts and existential questions.

Most recently, White and Arteta returned to Sundance in 2017 for their latest collaboration, Beatriz at Dinner. While the film’s structure is rather simple, its message should be viewed in broad scope, especially in light of recent socio-political developments. It portrays a day in the life of Beatriz (Salma Hayek), a medical and spiritual healer, who attends a business dinner at a wealthy client’s home. As the evening progresses, a rivalry quickly develops between Beatriz and Doug (John Lithgow), a corrupt, inhumane real estate mogul.

In a nuanced performance—she moves us deeply with only her eyes—Hayek leads us through interactions and conversations that touch upon classism, racism, and corruption. The wealthy guests at the dinner party assume that Beatriz is a server strictly based on her appearance, and they ask her to refill their drinks. Even the white servers pay her no credence, talking over her to present the menu, but loathe to interrupt the wealthy, white business moguls and attorneys.

The tension between Doug and Beatriz comes to a head when she sings a song about times gone by that can never be had again. Doug calls her out for her contempt of him, and Beatriz explains that the two of them may have been brought together by fate—for her to enact revenge on all the people he has wronged. Doug explains that there are many people just like him, and Beatriz agrees, telling him that it is all those people who have created the world’s suffering. “All tears flow from the same source,” she tells him. “You can break something in two seconds but it can take forever to fix it,” she continues. Beatriz warns the other guests that the earth is dying, and eventually, even the rich will be affected by it.

While some may find the film to be too heavy-handed in its approach, that’s the point the filmmakers are making: It is absolutely necessary that problems be addressed in such a direct manner, otherwise they will continue to fester. We cannot be passive like the other guests at the dinner party—we must be more like Beatriz, unafraid to address evils in an attempt to make the world a better place.

The common thread that connects these three movies is a powerful, even dangerous idealism and desire. Buck wishes that his relationship with Chuck could go back to what it used to be. Justine dreams of a more fulfilling romance with another man in another place. Beatriz longs to rid the world of its evils so that we may all live as one. The source of their dissatisfaction differs, the cause of their troubles varies, and the end results are drastically different for each film, yet Mike White and Miguel Arteta’s body of work continually reminds us to do one thing—be the best version of ourselves.

Watch Now: White and Arteta’s auspicious first feature, Chuck & Buck, now streaming for a limited time on Fandor.