The following interview took place at the Clift Hotel in San Francisco on May Day, 2007. Hal Hartley—who with his wife, Japanese dancer and actress Miho Nikaido, had recently relocated from longtime home New York City to Berlin—was in town to promote Fay Grim, the globetrotting sequel to his Henry Fool and, it turned out, the last feature-length film from the American indie auteur for the next five years.

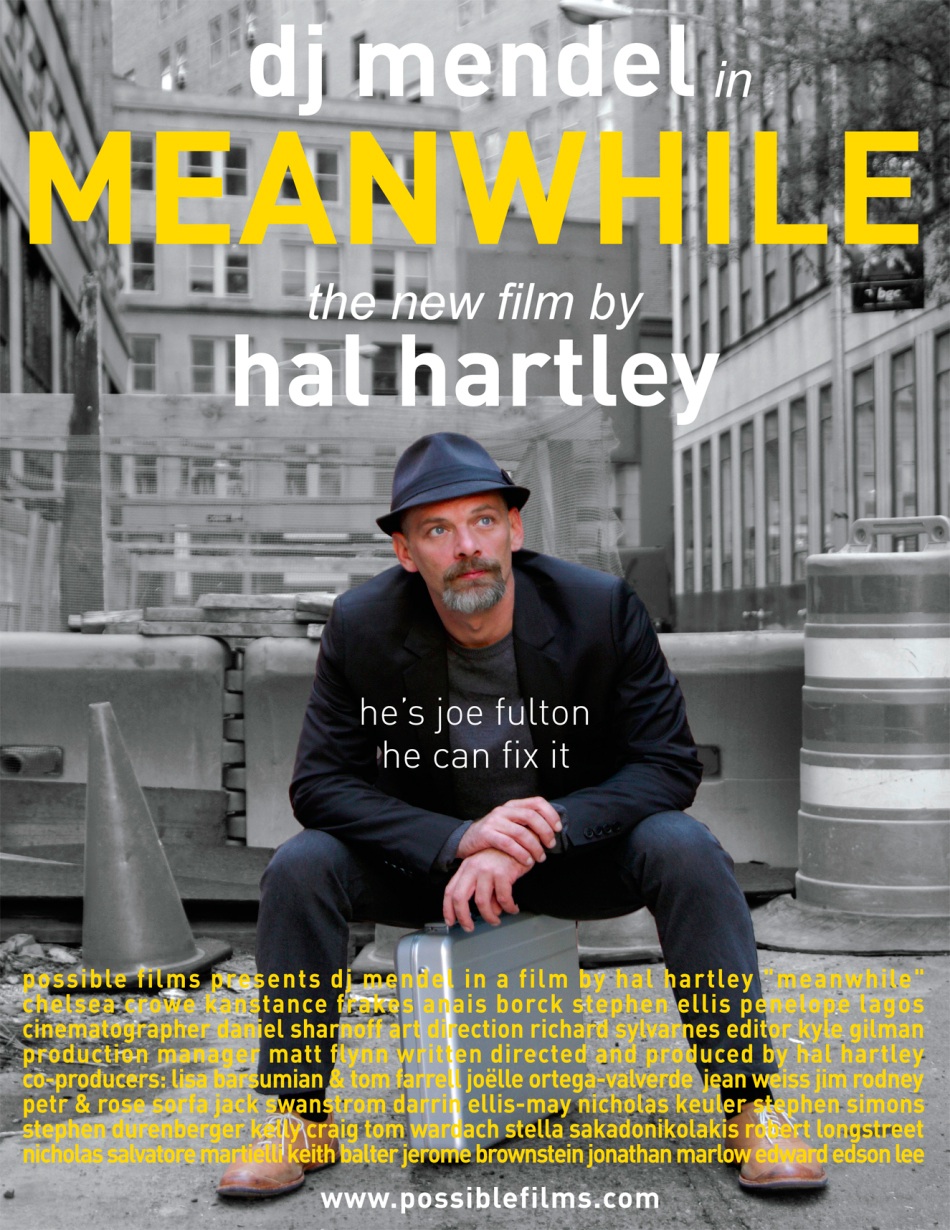

Meanwhile (which debuts on Fandor today and had its U.S. premiere in 2012) seems from its very title through its meandering plot to wink at the gap between features. Yet it’s not the case that Hartley was idle during that time. In addition to directing for the stage, pursuing various major projects like the still shelved Simone Weil biopic, writing a screenplay-patterned blog (“The Episodes”), writing and recording music (toward a 2012 CD, Our Lady of the Highway), and much more besides, Hartley put out five short-form videos in 2010. While only one was a documentary, all draw inspiration directly from the busy flow of life at that moment. Along with the real-life entries in “The Episodes,” they capture something of the unspooling quicksilver narrative of life; they capture and are life-as-film. But then, as Meanwhile too suggests, the two have never been really separated for Hartley—admittedly a strange condition for someone seemingly forever branded with the decade of the 1990s, but that’s another story.

Hal Hartley’s The Unbelievable Truth helped jumpstart the independent film movement in the U.S. almost twenty years ago. Hartley followed Truth with eight more features in the next ten years. Since then, changes in geography—yes, the quintessential New York filmmaker doesn’t live in New York anymore—and work styles have put a little more distance between Hartley’s pieces and also given the director a chance to experiment with form, as he explains in this wide-ranging interview conducted during his visit to San Francisco for the San Francisco International Film Festival in 2007.

Robert Avila: This is the third film you’ve made outside the U.S. What opportunities does filming abroad afford you?

Hal Hartley: Earlier they’d been aesthetic reasons [for shooting abroad]; there was nothing economic about it. This one posed certain problems. I was already living in Berlin, and the script of course had been written for Queens, but also for Paris and Istanbul. It’s not a totally small film, but we didn’t have the money to travel to all these places and do all these things there. And we couldn’t base it out of New York either. It’s just become too expensive there. So then we just reread the script. One thing I discovered right off the bat is that like ninety percent of the movie is indoors, which is unusual. So we started thinking about sets, building sets that would match the first film. But we got lucky. It was mostly about Parker’s, Fay’s, home. At the eleventh hour we found a German prefab Bauhaus neighborhood that had these homes that could be Queens, or Brooklyn. We had to change a lot of the details but the layout could definitely be a home in Brooklyn. It was just a lot of work doing location scouting, finding the interior of the French Ministry. Those kinds of things were easier because European cities all have that monumental eighteenth-century [building] somewhere.

Avila: Did this slow you down at all?

Hartley: No, we shot as fast as I’ve usually had to shoot in the United States. It’s only twenty-eight days, I think—less, like twenty-six. No, certain things were harder to find, like the big set for Fay’s home. That took us a long time. This really good locations guy, Roland Gerhardt, at the eleventh hour found [it]. Because a lot of the page count—if it’s a 130-page script, seventy pages happen in Fay’s house. So we knew that if we shot for twenty-six days we were at that location for like six or seven. Other things were kind of easy.

Avila: You say you were living in Berlin at the time. I read you were a fellow at the American Academy of Berlin. What were you doing there exactly?

Hartley: Well, it’s a kind of colony, like the MacDowell Colony, so they give you a stipend for three months to work on something that ostensibly has something to do with American-German relations or history, or just about Germany. I’d been working on a script for a long time about the life of Simone Weil, the French social activist, and she had spent some time in Berlin before the war. That seemed to be enough.

Avila: Are you still working on that project?

Hartley: Yeah, but it’s a long way off.

Avila: She’s a fascinating figure. A deep thinker, but also a pacifist willing to join the French resistance and so on.

Hartley: She’s a much more representative person of the time and the place than people think.

Avila: So you were based there.

Hartley: And I liked it. My wife, Miho, and I decided that some changes needed to be made. It was getting difficult to be in New York. A lot of our friends had left after the Patriot Act and things came in. We just really didn’t feel like that was the center of our lives anymore.

Avila: So that’s where you’re based now?

Hartley: Berlin is where we’re based. We keep a small apartment in New York, because she’s designing fashion and that work is in New York.

Avila: Getting out of the U.S., I think it’s probably a widespread urge these days.

Hartley: It’s uncomfortable here. It’s subtle. You don’t realize; the devil is in the details. You only realize after a couple of years, these laws that seem so abstract when you read about them in the paper, how they really are affecting your life.

Avila: Do you feel very far away in Berlin?

Hartley: No, I feel really at home in Berlin. Even though I can’t speak the language, if you can believe it. Much more at home than I’ve ever felt in the United States outside New York. And I guess New York was simply because of the density of family and friends.

Avila: I’ve found, living outside the country, it can be nice not to speak the language.

Hartley: In a way it’s very calming. I feel really calm walking around Berlin. It’s sort of an existential disconnect. Sometimes I used to hyperventilate, when I was first there. What happens if I get hurt? And I need to go to the hospital or I need help from my neighbors? Now I’ve accumulated a little bit more German. But there is that peace. When I leave my home, workshop, and I go down onto the street, I really feel free. I don’t have any obligations. It’s really quite nice to be an ex-pat. Also, the normal expectations of what one needs for one’s regular day is so different than in America. You see it with kids most obviously, with families. The poorest American I know who has a child has to have a separate room for all the child’s toys. Whereas in Germany and France it’s just not that way. We have such a weird insistence on giving them all that. They actually deal with the kids in a way. [Laughter.]

Avila: I’m wondering if being an artist in an environment where you don’t necessarily speak the language can help you focus.

Hartley: It lends a focus, that’s true. I guess certain people in my position might take a house in Spain, by the ocean, to really get away from everybody and work on something. Well, I’m a city person. I can’t go too far into the country. I don’t like to drive or anything. So Berlin is that place for me. I’m in the midst of the city. But one of the things I love about Berlin is that it’s got all the great things of a city but, also, it feels like being in the country really. There are so many trees; they have a big insistence on a kind of calmness, you know, the weekends are the weekends. I can be in my flat in Berlin for weeks at a time and not see anybody if I don’t want to. So I have been getting a lot done, preparing more work.

Avila: Do you find opportunities for creative mistranslation?

Hartley: A lot of my writing of course now has to do with this, an American being in Germany, or Europe generally, and miscommunications and discoveries that you only make in that manner.

Avila: Did you see Fay operating that way?

Hartley: No, I can’t say that those kinds of things affected that because Fay was written before. That was written in the years I was working at Harvard [2001 to 2004 ].

Avila: Did you always know you wanted to continue the story of Henry Fool?

Hartley: Using the word ‘continue’ is funny. It might be more accurate to say that I knew for a long time that I would like to make up a new story that utilized these same people. It’s the disjunction from one movie to another that will come to typify these films, I think.

Avila: Have people been commenting on how different they are as films?

Hartley: Most people just, rightly so, fixate on the characters. They ask, How was it to think what Fay would be like ten years later? How would she have grown from that girl? But in fact there’s lots of evidence in the first film. That’s where I went when I tried to figure out what I was going to make up to tell a new story with these people, I went back to the first film and made notes: Henry mentions South America; Henry mentions Paris. But for Fay’s character, towards the end, you could see that she’s not the same girl she was at the beginning. When she comes into the bar and takes her son out of the topless bar where he’s drinking with his father—she’s already gotten a little bit more responsible. And when she looks at the neighbor’s girl, Pearl, coming out of the house, which has to do with some bad shit going on with the stepfather. She started almost clueless but she’s learning.

Avila: Initially she’s just young, irresponsible, demanding…

Hartley: She just wants to get fucked. [Laughs.]

Avila: It must have been tempting to continue her development.

Hartley: It was. We just looked at what would be the most likely changes that would happen in a person, if they were raising a kid by themselves. And certain kinds of sadnesses have happened—her mother committing suicide in the bathroom, her husband going off somewhere because he killed the next-door neighbor, and her brother in prison. So there’s sadness and difficulty there that she’s got to bear up under. For the purposes of this movie, I really wanted her to be the representative American of a particular type that I hope exists somewhere out there. She’s perfectly well intentioned, but she’s uninformed, which I think you can say about a lot of the population here. But then, she’s actually quite smart and quite brave and deeply charitable. That’s the tragedy in this film. If she didn’t waste time trying to make sure that Bibi came along with them, she would have been reunited with Henry. So we’ll have to deal with that in part three.

Avila: It’s interesting, too, how Henry does and doesn’t develop. In terms of their relationship, specifically, he was always moving away from her in the first film…

Hartley: He didn’t want to be married. He was afraid of being tied down. But he was terrible drawn to her sexually.

Avila: It finally gets him to the alter.

Hartley: Yeah, he’s just a slob. [Laughs.] He’s just a child. But I believe him at the end of Henry Fool. He says, ‘I love you, Fay.’ And she kisses him and says, ‘Tough.’ [Laughs.] I’m just curious, in my writing now for what will eventually become part three I guess, I really want to understand more now about the nature of the attraction between them. I don’t really see this movie as being about this great romantic love and she’ll do anything to be with the man she loves. I think she’s over that. She’s trying to bring the family together.

Avila: It struck me that he’s still as restless and rambunctious as ever, but now it’s writ large in terms of geopolitics and international intrigue.

Hartley: The first one’s about the individual, Simon really, and the nature of influence. But to really simplify it: the first one’s about the creative act; the effect on the individual, the family, the community, culture. And then the second one is starting with the culture, but you’re seeing it through the prism of the experience of a certain family, a certain woman. So the third one, I think, will be different again. I’m feeling the rhythm of a conclusion happening. The third one will almost, I think, speak to the first one as much as the second.

Avila: How was it working with the same actors ten years later? Liam Aiken, as the now teenage Ned, for instance?

Hartley: That was his first role, when he was six years old. It’s his very first time in the movies. And he’s a good kid. He’s smart and he’s into it. I asked him already, I said, Look, this is definitely moving towards a number three, and that will definitely be about Ned. He’s a guitarist too, he’s got a band. So I asked him, Are you gonna stay an actor? Can I count on you for a third one? And he said yeah.

But it’s funny about Henry, Tom Ryan and I had this conversation about how he would be different. I remember Tom articulating it really well, saying, No, Henry doesn’t change. Henry is exactly the slob, the childish, self-involved but hilarious guy that he’s always been. The context changes but he’s like a rock at the center. I think there’s something in that. I think the third one could be really quite hard on him, without bashing him, but coming to the brutal truth about a character like that. I could definitely see the son saying, ‘You know, Mom’s in a Turkish prison.’ Or, think about it, if Fay is accused of treason by the United States—we’re the only country in the world that kills people for this. She could be executed. You can be executed. It could really come down hard on his father. This could definitely be a Luke Skywalker/Darth Vader type thing, like he’s going to kill the old man. But I could imagine him finally not doing it because he understands that this man is just a child. He’s a perpetual child. He doesn’t know what the implications are of everything that happens to him.

Avila: There’s also something mythical about him.

Hartley: Even before I wanted to make the second one, I wanted to make a contemporary American classic of the Faust type. And he was the Mephistopheles, and Simon is the Faust. Even when Goethe and Marlowe were doing their Fausts, Faust was already a stock, standard story. I think something about the perennialness of these characters means that I can work with them for a long, long time. We’ll have to see.

Avila: You’ve always scored your films yourself, and the music is invariably an integral element in them. How do you go about creating the music?

Hartley: Usually, it’s the old fashioned way. I cut the picture and the dialogue, and then they’re on cassette tapes—although I should be doing this on computer now. Anyway, so I have a TV and I’ll just play to it. Maybe while I’ve been making the film and editing it I’ll tinker around with piano trying to find themes. In this case, it was quite fun because this Henry Fool music already existed. So I listened a lot to the music I made in 1996-1997. It took me a long time to find that chord [hums main theme], which is a classic, carnival, gypsy-type thing. But I couldn’t remember the actual [chord]. I finally found it. I wrote it down. I think only once do you actually hear chords played that way—I think it’s on the CD but it’s not in the movie—but the rhythm is played as an arpeggio. That kind of opened up a whole world. I think the music here is very much more affected by music from No Such Thing and Girl from Monday. It’s less machine music than Girl from Monday. But Girl from Monday also, the kind of strategy there was mechanical music with acoustic instruments. There are lots of cellos, and clarinets—but also program drumming, banging, electric guitars and stuff. This one left that kind of stuff out, but it’s mostly an instrumentation that’s been evolving since No Such Thing.

Avila: Do you play with other musicians?

Hartley: In that sense, it’s all mechanical, it’s all done [by me] on keyboard.

Avila: Did you study music?

Hartley: No. I studied classical guitar when I was a teenager, and some sight-reading then. Actually, in the year before Henry Fool, my music partner for a long time, Jeff Taylor, moved back here to the West Coast to start another career. When we made all that music from Simple Men, Amateur, Flirt, I was always at the instruments and he was doing the thinking about harmony and theory, and would suggest things. I really grew dependent on him. When he was leaving I said, OK, we’re going to have to get serious about this. So I took a thirteen-week night course at the New School on sight-reading, which just reminded me of all that stuff I knew as a kid. And it gave me a lot of confidence. Without a doubt Henry Fool was the most confident music I had made myself. Jeff thought so too. He called me immediately when he saw the film and said very good work. So since then I’ve had a lot more confidence.

Avila: Do you enjoy playing music generally? Is it a daily activity?

Hartley: No, it’s really dictated by movies. I almost never—this is a typical circumstance: in eight weeks, nine weeks while we’re doing the sound editing on Fay Grim in one room, I’m in another room where I spend most of the day making music and recording it. When I feel I have a bunch for one part of the movie I’ll go over into the next room and I’ll put it into the computer. That’s all pretty exciting. I generate an enormous amount of music that way. Then we do the mix of the film and I’m away from the music for another month. Then when everything chills out, and the movie’s done and it’s delivered and my time is my own again, I usually go back and start listening to all the recordings again, thinking to put together a CD. So I’m looking for the best and the most representative. And that leads to me redoing them—because music in movies needs to be less than it is if you’re just listening to it in a room. Trying to redo it as a listening experience solely, that’s great. I love that. That’s the only time I’m just being a musician every day. Then I’m finished and I probably won’t take the sheet off the keyboard until the next time.

Avila: Do you follow music in Berlin?

Hartley: I see a lot of classical, jazz, and contemporary orchestral stuff. I like to go to bed too early to keep up with the rock scene. I have lots of rocker friends who I just can’t—I never see them rock.

Avila: Your re-approach to the filmmaking process, technically and aesthetically, in Girl from Monday, with the digital cameras, smaller crews, etc.: how did it feed the production of Fay Grim?

Hartley: It’s the smaller movies, the things that I’ve been shooting in conventional DV Cam, that led to me to start doing all the Dutch angles, for instance, playing around with that kind of stylistic [approach]. But also those three films that preceded it were all conceived around the same time. It was part of a larger project (I’m talking about The Book of Life, No Such Thing, and Girl from Monday) to treat a certain big subject—faith and the body, or our spiritual life and the body—from different angles, all using genres. So I did a lot of studying of genres. With No Such Thing, watching monster movies of every variety. Asking, what do all of these movies have in common? There are always funny things. In so many of the Japanese Mothra movies, and Godzilla, it’s a female journalist who has to go out and investigate—those common things I wanted to draw on. I think I was quite studied in that kind of research. So when I knew that Fay Grim would have to start as a kind of espionage thriller satire I knew exactly what to do. Get the newspapers, get real things out of the international section; and reading spy novels, watching spy movies.

Avila: So you immersed yourself in those kinds of sources?

Hartley: And became sharper at saying, This is something that happens in every spy movie, whether it’s James Bond or it’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, there’s always that moment when there’s a flip, when the person she trusts turns out to be lying, not who he was. It’s good. Sometimes making use of a genre can allow you to treat quite serious stuff in a light manner. You can be in fact more poetic about it. In a way a little bit more ridiculous about it and still maintain a little sincerity.

Avila: So it frees you.

Hartley: It can, yeah. Giving yourself to a form, or to a genre as we say it in storytelling. You hear musicians talking about this. They say, I have all these ideas but I don’t know if it should be a fugue or some other form. They feel it, they hear it, but they haven’t discovered yet what’s the best form for it.

Avila: Prior to this you hadn’t concerned yourself consciously with genre?

Hartley: Only with Amateur. And that was very early on. I didn’t do quite as much of that research. Back then I didn’t try to look for those typical things. I just remembered detective shows from television in the seventies and was kind of working off of what I remembered.

Avila: I was looking over that interview you conducted with Godard back in 1994. There was a question you asked him about new technologies, the possibilities concerning new modes and networks of distribution and so on. He was a little dismissive or pessimistic about it, but you seemed enthusiastic.

Hartley: That’s what everyone was talking about in my group. He talks poetically, so it’s hard to sort it out, but I don’t think he’s quite as pessimistic as it sounds brutally right there on the page. In a way, he’s just admitting that times are changing. But it’s like the political economy of filmmaking, he sees ridiculous things, like it’s clearly moving toward smaller screens. Doesn’t he say something like that?

Avila: He does.

Hartley: ‘The apartments are getting smaller so why should the screens get bigger?’ I think he’s nostalgic for the old big communal experience. But I’m certain that at that time that was not how he experienced films anymore. It’s not like he went out to the movie theater. He had like Tom Luddy sending him DVDs of everything.

Avila: Although he wasn’t far off, seeing as everybody watches movies on their computers, and my apartment, anyway, keeps shrinking.

Hartley: He wasn’t, no.

Avila: More than ten years later, what do you see, with the realization of these new networks? The SF International Film Festival, for example, has a pilot project this year to send films out over the Internet rather than bringing films and people exclusively into the physical festival grounds per the old paradigm. Do you see yourself in these new distribution networks?

Hartley: Yeah, of course. I think at that time, in 1994, I probably believed these things would be a choice for us. And now I understand, this is not a choice. Movies are a commercial art and commerce will determine how people enjoy them. It’s always been that way, from Nickelodeons on. So I don’t sweat it anymore. A film like Fay Grim, it’s made with new technology, but it in fact is doing what movies were doing seventy, eighty years ago. But, yeah, the manner of getting it out to people is different. And there are people who know more about that than I do. I’m not really going to sweat it so much.

Avila: You’re still doing basically what you’ve always done?

Hartley: In some ways. When I was here [in San Francisco] with Girl from Monday, that was probably the most radical thing I’ve ever done, to think, Well, we’ve made this movie in such a different, alternative manner, what would happen if we just amplified that a little bit more and just considered distribution as part of the production process? You know, I don’t regret doing it but it was way, way too much work.

Avila: To do it yourself?

Hartley: Yeah, to take it around the country… But that would be considered terribly old-fashioned now.

Avila: Do you see a lot of Hollywood movies? I was curious what you were reading and seeing these days.

Hartley: In Berlin I go to a rental place. It’s just amazing how people all over the world watch American movies, mainstream movies. So it gives me an opportunity to catch up on things—movies that I probably would not go to a movie theater to see. They’re not that special to me, I don’t have that much anticipation, but I do want to know what’s going on.

Avila: What have you seen lately?

Hartley: I saw, oh, they call it High School Confidential over there. It’s the one about Evan Rachel Wood in high school. Oh god, what’s it called here? It’s a satire, real dark, these high school girls who fake a sexual harassment thing on a teacher. Pretty Persuasion! I thought that was pretty good. The writing was pretty good. And this girl, who was very young, who had been Rachel Wood [Kimberly Joyce], was really interesting. I actually see at least seven or eight films a week on DVD, and I do write them down but my book is in Berlin. To tell you the truth most of them go in and right out again. But the past couple years I’ve watched Terrence Malick’s Thin Red Line at least once every two months. And The New World, which I just think is just extraordinary. I bought a DVD of that about a year ago. That’s like a once-a-month thing.

Avila: They’re great films, poetic films, but what in particular draws you to them?

Hartley: It’s of course the kind of filmmaking that I don’t do at all, so it’s not about that. But I learn from them. He’s really great at telling the big old human reality stories, in epic size. He gets great performances. He spends a lot of time looking at people’s real characteristics and weaving them in. That’s why they’re very expensive films; they’re certainly not sell-out things. I think they’re the best example of what big American filmmaking can be. And they’re deep, and they’re beautiful. His love of language and how he uses it is really quite great. I mean, that scene between Elias Koteas and Nick Nolte in Thin Red Line, when Koteas decides not to carry out the attacks the way Nolte wants him to, is just classic.

Avila: I saw Days of Heaven again recently. They are like cinema’s version of the novel…

Hartley: And he translates it into images, really good ones. A lot of the times, you think of a Malick film you’re not thinking about words. You’re not thinking about dialogue, you’re thinking about nature, you know there’s this whole thing in every single one. You watch all four of those films, just the shots of the moon, the grass, human blood. Man in Nature. Man is natural, but Nature is against him. He’s got a real serious thing he’s working on. It’s probably in his blood. And it’s something I always forget but how powerfully influenced I was right at the very beginning by Days of Heaven and Badlands in the seventies. I saw Badlands on TV late one night, in like 1975, 1976, and I was like [makes gesture of amazement]. I think probably my first group of Super 8 films through art school and into film school were very much like that—but without any understanding. [Laughter.]

Avila: Were they narratives?

Hartley: They became narratives as I began to understand that there was such a thing as narrative. I had to have some older people, teachers, point that out.

Avila: Are you conscious of how your approach to narrative has evolved over time?

Hartl