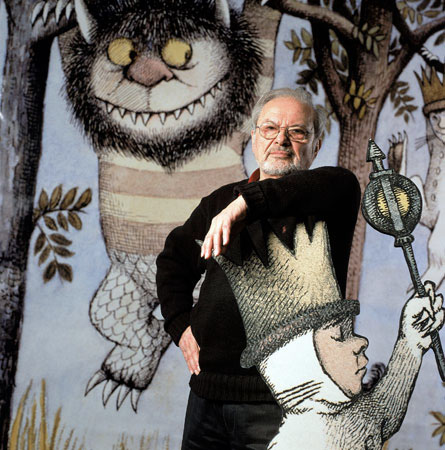

“Maurice Sendak, widely considered the most important children’s book artist of the 20th century, who wrenched the picture book out of the safe, sanitized world of the nursery and plunged it into the dark, terrifying and hauntingly beautiful recesses of the human psyche, died on Tuesday,” reports Margalit Fox in the New York Times. Sendak was 83. “Roundly praised, intermittently censored and occasionally eaten, Mr. Sendak’s books were essential ingredients of childhood for the generation born after 1960 or thereabouts, and in turn for their children. He was known in particular for more than a dozen picture books he wrote and illustrated himself, most famously Where the Wild Things Are, which was simultaneously genre-breaking and career-making when it was published by Harper & Row in 1963.”

Where the Wild Things Are became a film, of course, in 2009, with Spike Jonze directing from a screenplay by Sendak, Jonze and Dave Eggers. Reviews were generally positive but mixed—I spent a couple of weeks rounding them up at the time. The following year, Jonze interviewed Sendak for the HBO documentary Tell Them Anything You Want: A Portrait of Maurice Sendak.

Just last month, when Amos Vogel passed away, I noted that Sendak drew the illustrations for Vogel’s own children’s book, How Little Lori Visited Times Square.

“Mr. Sendak was shaped foremost by a sickly and homebound childhood in Depression-era Brooklyn, the deaths of family members in the Holocaust and vivid memories as a youngster reading about the kidnapping and murder of aviator Charles Lindbergh’s infant son,” writes Becky Krystal for the Washington Post. “An admitted obsession with ‘children and their survival’ and the ‘humongous heroism of children’ fueled a career of groundbreaking darkness in children’s literature. President Bill Clinton presented him with the National Medal of Arts in 1996, saying, ‘His books have helped children to explore and resolve their feelings of anger, boredom, fear, frustration and jealousy.'”

Here you can watch President Obama reading Where the Wild Things Are.

Updates: “While everyone in Sendak’s family told stories, remembered gruesome fairy tales and Jewish folklore, and drew pictures, his other childhood influence was the cinema – Busby Berkeley, Buster Keaton, Oliver Hardy, King Kong and Disney,” writes Stephanie Nettell in the Guardian. “Another great love was his sister, Natalie: he was a sickly child, constantly quarantined (‘I learned early on that it was a very chancy business, being alive’) and missing school, so Natalie, nine years older, was always having him ‘dumped on her,’ and he remembered both her great love and her demonic rages. Outside Over There (1981), the last of the trilogy that began with Where the Wild Things Are and continued with In the Night Kitchen, was his most personal book, and his favorite, a tribute to Natalie ‘who is Ida, very brave, very strong, very frightening, taking care of me’ (the ‘Baby’ of the story). He saw Ida as the favourite child he never had. Although he would have dearly liked to have children, he never married and never told his parents that he was gay: ‘All I wanted was to be straight so my parents could be happy,’ he said in a New York Times interview in 2008. ‘They never, never, never knew.'”

See also: Avi Steinberg‘s interview for the Paris Review last December; a visit with Art Spiegelman; Flavorwire‘s quotes and images, set together as a tribute; another excellent collection at Our God is Speed; Sendak’s 1993 New Yorker cover; and, via Ed Gonzalez at the House Next Door, Cynthia Zarin‘s 2006 profile of Sendak for the New Yorker.

Updates, 5/11: Dallas Clayton, Howard A. Rodman and Michael Tolkin remember Sendak in the Los Angeles Review of Books and, for the New Yorker, Sasha Weiss discusses Sendak with Art Spiegelman.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed.