[Editor’s note: This is one in a series of articles highlighting new features hitting Fandor from the Criterion Collection via Hulu Plus. This feature focuses on films from the “Island Life” theme.]

Near the beginning of It’s the Earth Not the Moon (2011), Gonçalo Tocha’s delightful documentary essay on Corvo, the northernmost and least populated island of the Azores, the director proposes to film “every corner of the island,” “every face, every house…every tree, every rock, every bird”—a quixotic fantasy sustained by the island’s radical enclosure. One might conceivably know everything on an island, just as the island has a way of laying bare one’s interiority. It’s no surprise that Roberto Rossellini set his sights on volcanic Stromboli as he began to steer neorealism towards subjective experience; certain locations simply demand psychological reckoning.

Stromboli (1950) is the first of three films Rossellini made with his paramour, Ingrid Bergman. Here she plays a Lithuanian refugee who marries out of a POW camp only to find herself bitterly alienated living on the cloistered island. Looked down upon by the villagers and eventually locked in her own house by her well-meaning fisherman husband, Karin comes to seem a perpetual captive (Italian audiences would have been aware that, as Rossellini noted in a letter to Bergman, “the Lipari islands…earned a sad fame during fascism, because it is there that the enemies of the Fascist government were confined”). Stromboli is very much a film about what happens after the war, with Karin’s unrelenting suffering making for a bleak omen of the peace.

Karin brings some of this woe upon herself, though Bergman’s keening performance suggests that many of her character’s complaints—that her husband doesn’t make enough money to support an European lifestyle, for instance—represent failed attempts at naming a deeper angst. Essentially dissatisfied, Bergman’s heroine is something new in movies. Her character’s social exclusion is mirrored by the glaring contrast between Bergman the movie star and the non-actors playing the villagers—a disparity that splinters Rossellini’s vaunted neorealism. In one memorable sequence, we watch gigantic tunas being netted and hauled up onto slender boats. It’s a typical bit of neorealist ethnography, but the writhing fish cannot help but read differently in light of Karin’s torment. Trailing after her movements through the mazelike town, Rossellini’s camera is thoroughly infused by her wayward spirit.

Karin finally wishes only to escape, an impasse that leads Rossellini to grace. Determined to reach the other side of the island, she ascends the spewing volcano. The compositions begin to break down in swirling black smoke and the stark inclines. Karin collapses, seemingly forsaken, and then a moment later awakens on the freshly becalmed ashen surface. She cries out for God, birds flying overhead (Rossellini likens Karin to St. Francis in his letter to Bergman, though this saint’s life is definitely colored by earthly desire—compare Bergman’s full-frame prostrations with Falconetti’s shoulders-up martyrdom in The Passion of Joan of Arc). In her despair, she is exalted; this is where the picture ends.

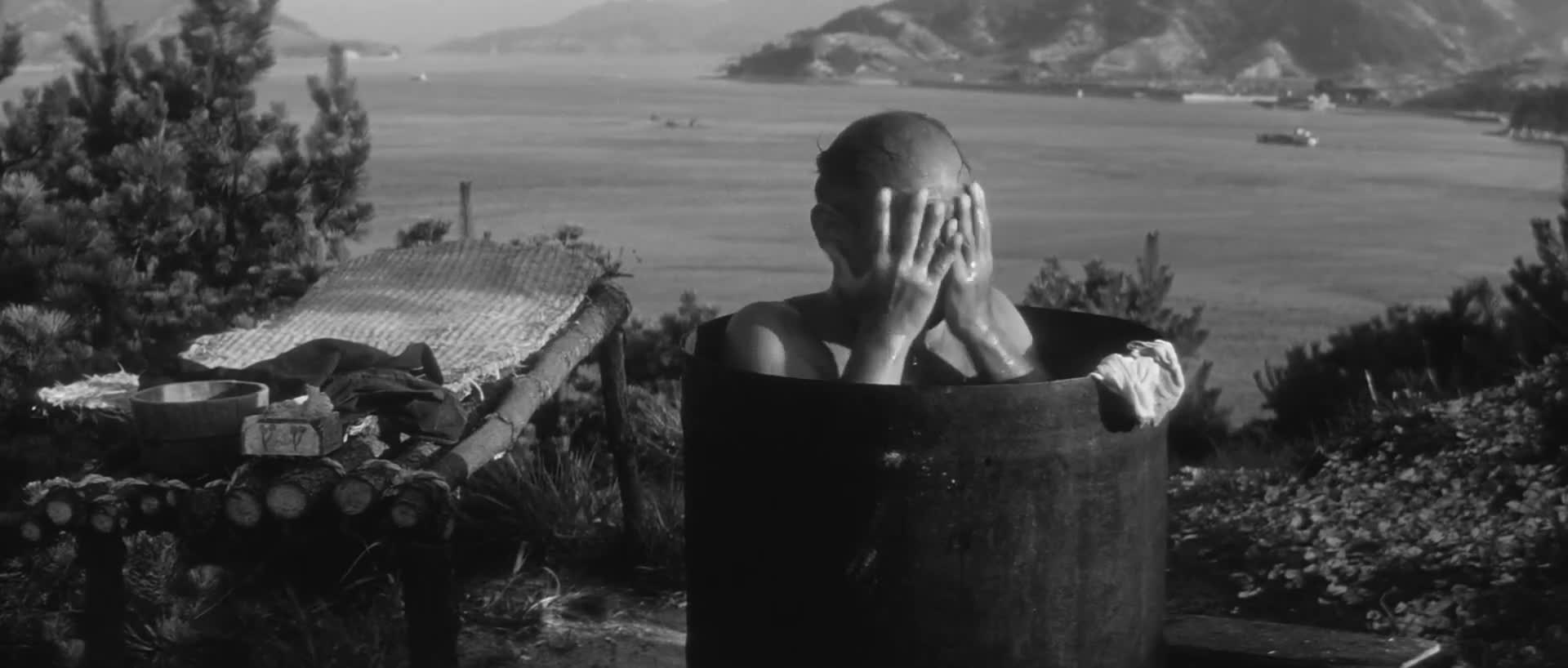

Audiences have long argued over the validity of Karin’s redemption, but it seems clear that the miraculous conclusions of Rossellini’s Bergman trilogy served as a provocation for later filmmakers who saw little reason to hope for the best. The island setting’s tangible existentialism made it a key figure for the burgeoning art cinema movement of the early 1960s: Through a Glass Darkly (1961), the first of many Ingmar Bergman films set on Fårö; Naked Island (1960), Kaneto Shindô’s lyrical depiction of a farming family’s hardships; Peter Brook’s adaptation of Lord of the Flies (1963); and Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’avventura (1960). Contra Rossellini, these are all films that marshal considerable aesthetic resources to suggest man’s estrangement from God. Most influentially, Antonioni allows his narrative to unspool when a society woman disappears during a pleasure cruise through the same rocky Aeolian Islands.

As this premise suggests, Antonioni is especially alive to the twinned aspects of idyll and isolation clinging to the island imagination. The long sequence of the yachting party’s search for missing Anna (Lea Massari) stands as one of modernity’s ur-images of alienation, with Antonioni taking advantage of the literally uneven terrain to create a psychologically inflected landscape that’s at once mercilessly exposed and full of blind spots. Jutting rocks conceal entrances and exits, and Antonioni further emphasizes the distance between figures in deep focus compositions in which the characters appear either stiflingly near or at a far remove. Time itself drags to a standstill in the open-ended shots. A few members of the party, including Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti), Anna’s lover, and Claudia (Monica Vitti), her friend, spend the night at a fisherman’s shack—a character hearkening back to Rossellini’s neorealism, but the perspective of this film is too winnowed to see him in his ordinary working life. As Vitti opens the shack’s door to a glorious sunset, the beauty of the scene seems only to taunt her diminished existence. Here are characters who ordinarily feel that they could be anywhere—here or there, it makes no difference. The island allows for no such detachment. You know exactly where was you are on the island, and that is exactly what makes it so disorienting for a modern person. L’avventura conveys this paradox as no film before or since.

The image of the island continues to haunt Claudia and Sandro’s drifting through hotel rooms and abandoned towns on the mainland, their misplaced love affair spiraling into oblivion. The indelible tracking shot of Vitti navigating a village of leering men recalls Bergman’s similarly sexualized ostracism in Stromboli, but of course Karin is literally a displaced person whereas Claudia’s estrangement remains abstract. L’avventura is justly celebrated as a quintessentially modern film, but fifty years later later one might easily argue that Rossellini’s refugee is the more resonant figure than Antonioni’s disaffected bourgeoisie. Whatever it is that ails us, the island is sure to give it a form.