Lyda Kuth didn’t even know she was making a personal documentary. When she set out to make her first feature, Love and Other Anxieties (2011), she was interested in taking an honest and humorous look at love and marriage. But as she got deeper into the filmmaking process, her documentary revealed itself as a story about her own evolution as a person, a partner, a thinker and an artist. She started filming around the house, to the chagrin of her mild-mannered husband and teenage daughter. She dug out old photos from her childhood and started to think deeply about her mother’s own relationship to love, happiness and womanhood, and how she in turn influenced Lyda. And what started as a pet project, what was supposed to be a twenty-minute short, became a universally relatable feature film, a personal doc in the mold of Ross McElwee, Edward Pincus and Doug Block.

Kuth came to filmmaking later in life, having worked for many years on the philanthropic side of film. Being Executive Director of the LEF Foundation, an organization that supports documentary filmmakers throughout New England, she’d long felt the itch to create, and for this project she was able to draw on the knowledge of a great community artists that she’d befriended over the years, including Mary Jane Doherty, who here serves as DP and Co-Producer, and award-winning filmmaker Lucia Small (My Father, the Genius) who edited the film. She talked to me about giving cinematic form to her own life, letting art be a catalyst for that life, and learning to like being the center of things.

Keyframe: At the start of the film, you talk openly about how you’d always wanted to make a film, and that this is that film. Now, even if that was the spark, there’s a sense from the viewer of ‘maybe don’t tell people that.’ But it’s essential to say this, because what the film became is a reflection of who you are and what you became. At what point did you realize that such a slight provocation for making the film was actually a very significant one, and was worth including from the top?

Lyda Kuth: It’s really dicey when you say, ‘I want to make my first film.’ Who’s going to sit and watch the next fifty-nine minutes of that? [Laughs.] But just in terms of form, we debated long and hard about how to structure this film. We needed to make it a journey. And we didn’t find the beginning until we got to the end. The film became much more than about love—it became a midlife story. And it became about me coming out in a lot of ways. There are a couple of things you see consistently in personal docs, and I think one of the reasons you see them are because they’re part of the form, and a form has limitations. One of them is to make the filmmaking visible and audible. Ed Pincus does that—he fools with the camera, he makes it obvious. Ross McElwee shows himself in front of the camera, setting it up. I didn’t even know it was a trope until long after we used it. We thought about [my talking about wanting to make a film], because we didn’t want to make that an excuse, to give me a lot of latitude. But it belonged in the film because of what happened three quarters of the way through, which is that it turned out that film meant a lot more to me than I knew. Yes, I really did sit down with [DP and Co-Producer] Mary Jane Doherty and say, ‘I don’t have any ideas for a film. I just want to make a film.’ And I felt kind of like a loser for that reason. But I said, ‘I am reading this book On How Love Conquered Marriage. Isn’t that a great title?’ And she said, ‘Why do you think that? Let’s just make a short film about the absurdity about trying to make a film about love. About how nobody and everybody is an expert on love.’ And she understood that it had a sociological relevance. Which was that everything is in so much flux. Stephanie Coontz [the author of On How Love Conquered Marriage] says in the film that there’s been more change in the institution of marriage in thirty years than in 3,000 years. And it’s true. So I knew it was a moment. What we did is decide to take an ironic view, almost, in going out and interviewing people. It so happens that Mary Jane’s style of interviewing is not being behind the camera, but to be in it. So it wasn’t until the day that we were going to film Stephanie Coontz that MJ said you’re going to be in it. She’s a very spontaneous person and it happened that way. I was suddenly in the picture.

Keyframe: So it wasn’t going to be a film about you at first?

Kuth: Oh my God, no, that’s how it happened. Over a year’s time we shot filmmaker Josh Safdie and one or two other people. And then I actually put it away for about six to nine months. I had a fantasy that I would edit myself and it would be a short film, and I would have a reason to learn Final Cut Pro. But I realized that if I was ever going to do anything with the footage, I would have to invite an editor in. So I sat down with [Editor] Lucia Small and we watched what I had. Which was maybe twenty hours at the most. We laughed a couple of times, and she said I think there’s a film here. We were thinking [the film would be] twenty minutes or so. We started cutting a few scenes, and then showed it to a few people, and we knew we needed a through-line. That’s when it became clear that Lyda was in every shot. That Lyda is on a journey, and what she’s trying to answer is at the heart of it, and she’s got to dig at it. It was probably no mistake that it was Lucia [I brought in], because though I had no intention of making a personal film, on some level maybe I knew it was going to be a close-to-my-heart kind of film. So that’s when we shot interstitials, and that’s when I brought out photos of my family. That’s when it all happened, in the edit room.

Keyframe: Is that when you wrote the script as well?

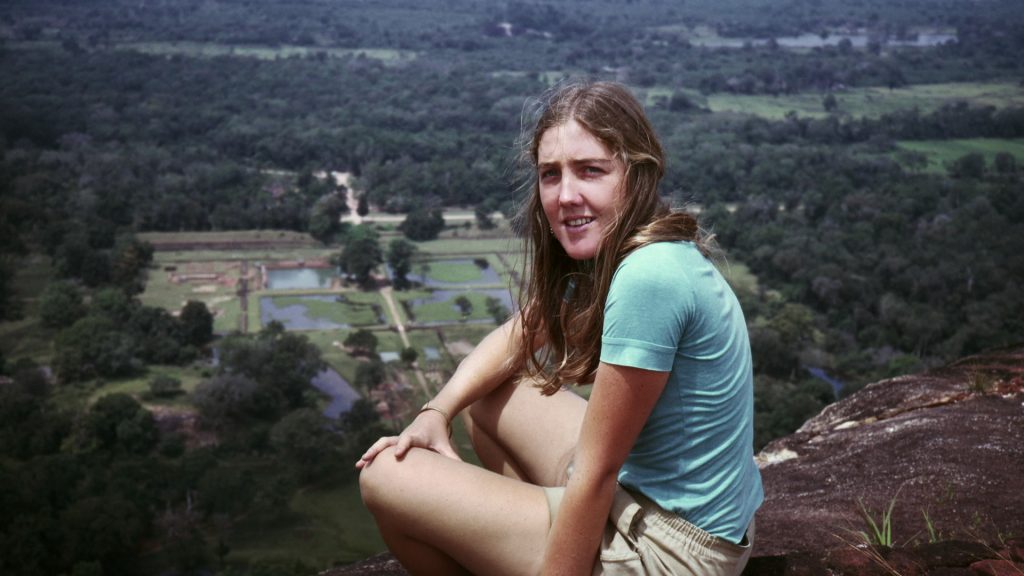

Kuth: Yes. The writing is why it took a year and a half to edit. We’d do some of the writing, say about what I would need to say about my mom, and then we’d go find images for it. We rewrote and recorded a lot. It was a lot of work. Lucia and I wrote it together, and that’s how we began to hang the scenes in the story. We’d ask the question: what do each of these scenes seem to convey? And then we’d understand how things found their way into the story.

Keyframe: You end the film with the notion that the film caused conflict for you—conflicts that didn’t exist previous to making the film. In that respect, was film a catalyst for you? Or was that just a convenient illusion for your art?

Kuth: No, it was definitely a catalyst. That’s almost the embarrassing part. I think every film a filmmaker makes, whether it’s about themselves or not, changes them. And so this film definitely was a catalyst in many areas—intellectually, thinking about the issues, emotionally, moving through some stuff, and just in my world. Me in the world changed once I made a film. It had a lot of ripples.

Keyframe: What about that translation to us? Because I think the film can also catalyze the viewer to reflection and self-identification. Since this is a personal film, and the language is about you throughout, how do you bridge the gap to make a film that others can relate to themselves?

Kuth: Well, you hope it happens.

Keyframe: But you’re also constructing it to happen, right?

Kuth: As best as you can. We were always wrestling with how much to expose, and how to create a film that doesn’t hit people as self-indulgent, or too much about you working out your own issues through the film. We thought we had a universal subject in terms of the context around these issues, which is so in flux for all these different age groups. But when I realized it was a midlife film, and that there could be a resonance for this kind of work. But what makes it universal in the end is how honest you are. And if you don’t appear to be honest you’re not going to catalyze anything. I had been wrestling with some deeply personal stuff, and I felt really exposed. So we talked to [filmmaker] Robb Moss on the phone, and he said you’ve got to go there yourself. You have to be really honest with yourself about what is this thing you’re touching on. And you have to really know it and own it. That doesn’t mean it has to be in the same way in your film—you may not bring the same level of exposure or self-confession. But unless you really own it, it won’t work. And that was really good advice.

Keyframe: You say at the beginning of the film that you don’t want to make a personal doc. Was that because of your shyness, or because you had a perception about personal docs that made you disinterested?

Kuth: I’ve always been a champion of personal docs, they’ve always resonated for me. I never imagined that I would make a personal doc because I couldn’t imagine exposing myself—to the film community, more than anything else. I already had this professional profile. But the fact that I ended up making what I think of as an essay film, which many personal docs are, is not surprising. Because I must feel on some level that something genuine [is happening] on camera is meaningful. I think it was more that I couldn’t imagine coming out like that. But as it turns out, I can withstand the camera. I’m shy and I’m not shy. Clearly, if I actually did this and put it out there and did Q&As, I can’t be that shy. And I think I’ve changed over the last seven years. People who knew me were like, but you’re such a private person, Lyda. They couldn’t believe I’d made this film. Then the people who really knew me said, nah, you should know her a little better.

Keyframe: You worked on it for how long?

Kuth: Five years, with intermittent editing.

Keyframe: Were you watching other films during that time? Or were you trying not to?

Kuth: Truthfully, I feel that I have a lot of films still to see. You always feel that. I had seen the seminal ones along the way, Ross McElwee’s films, some of which LEF had supported. I knew Robb Moss’s films and Ed Pincus’s films. The earlier stuff, like Miriam Weinstein’s films, I had not tracked down. And no, there was no formal intellectual information gathering of any kind. Just in the room making the film, unconscious, quite frankly, of the kinds of tropes I stumbled into. Such as in order to be a trusted guide, you have to expose your foibles. If you’re not going to make fun of yourself, they’re not going to trust you. That’s why Lucia was so pleased with the hairdressing scene coming early. Because how could I look worse than that? Ross does that really early on in his films, and really well. And also this idea of revealing the filmmaking process.

Keyframe: Yet you were intuitive about that, it wasn’t premeditated.

Kuth: Totally intuitive. Even though Lucia knows the form, we never sat down and talked back about how it should happen. With documentary, I don’t think there’s a million ways to go with form. Every form has its dimension, and you work within that form. What evolved out of Ed’s and even Ross’s work, there’s stuff you can take further, but you really start to see how it’s not hugely different.

Keyframe: Maybe that’s why when the form is stretched it can feel more significant.

Kuth: And that is important. The same way that Montaigne’s essay was a new literary form—something significant happened and then it was a form we all could use.

Keyframe: There’s always the chance that a viewer of a personal doc is going to think, ‘Why should I care about your life?’ Did you have conversations with yourself to negotiate that inevitability?

Kuth: Oh yeah. We started every morning with that. Lucia would go, ‘why would someone care about this?’ That question is constantly there for personal docs. I think it’s interesting how people are harsher with films as opposed to a [written] personal essay. Everyone knows that with a personal essay you’re taking your own experience and expanding it out. The heart of what I was trying to do was say, here’s my experience, here’s what it’s like to have ambivalence about love, this thing that people don’t like to talk about. Going back to Montaigne—you test it, you taste it, you try it, you’re not trying to preclude anything, you’re just putting it out there. With a personal doc, you’re not telling anyone how they should do something, you’re just revealing how things happen, as honestly as you can. But then people will yell at the filmmakers for doing this, like, ‘Who do you think you are, and why would we listen to you?’ I find that interesting, that there’s a bit of that prejudice, and I’m trying to understand a little more about why. What’s it about a filmmaker and film that can cause that?

Keyframe: Are you sacrificing yourself to the process in some way, knowing that we might skewer or claw at you? Are you constantly conceding that?

Kuth: By the time you’ve accepted you’re putting this out to the world, you have to. There were pretty big moments of reveal for me, but by the time I showed it to my husband and daughter, I had already dealt with my fear around it. I had dealt with it by getting it out, saying it in the editing room, working with it, refusing and accepting it. So by the time you put it on the piece of paper, your sense of exposure is over.

Keyframe: If the exposure has already happened along the way, what does the film become when you show it to others? You called yourself Lyda earlier—do you become just a character?

Kuth: This may be too Pollyanna-ish, but it’s a little like I’ve really become a touchstone for other people’s experiences and reactions. People tell me their stories. Somehow you have a certain freedom after you’ve revealed yourself. I can talk about these issues in a more lighthearted and compassionate way.

Keyframe: The assumption might be that you have the hugest ego about yourself to make a film like this, but it actually shows a lot of courage and generosity to present yourself this way.

Kuth: It really is something other than ego. And for me it came out of a desire to connect. My desire to connect with other people, and ultimately with an audience.

Keyframe: Which is interesting, considering where you started and where you got to. From just wanting to make a movie to then having it seen by many people, who can interact with it and you. And yet, what’s the point if you’re not going to communicate in the end?

Kuth: Exactly, what’s the point if you’re not going to connect? When I detect a real genuine desire on the part of the filmmaker to communicate and set a relationship up with their audience, whether it’s subject based or a work of advocacy or a personal doc [that’s when I connect with it]. It’s probably why I have a little less patience for avant garde stuff. And it makes sense that I would make something very different from that. It’s a standard value for me. It’s about makers connecting with their viewers.

Keyframe: I gather you weren’t shooting for a certain endpoint, but came to it organically.

Kuth: We created our chronology by my journey. Figuring out what points we wanted to have. Someone described it as feeling like you’re with somebody and the talk gets deeper. Even on an intuitive level that’s what we began to understand. Like most filmmakers, there are certain pieces [of the film] that I don’t think were totally, absolutely cooked. I feel that way about the end, that it’s a quiet and maybe abrupt end. But it really captured the nature of how I felt about [life and love]. That it’s iterative. My understanding is that disruptions are OK in order to grow, and that’s what I wanted to leave the audience with.