In the rapid evolution of film style in the first twenty years of cinema, from the earliest shorts by the Lumieres, the Edison Studio and Méliès to the narrative storytelling of D.W. Griffith, editing is king. It is, we are told, the foundation of film grammar. It gives the filmmaker a tool to direct our attention, brings us from the general to the specific with cut-ins, provides point and counterpoint with cross-cutting, provides intimacy, slows the action down to let us absorb the emotional content of a scene or build suspense, and speeds it up to increase anxiety and tension in action sequences.

As Griffith created more sophisticated narratives with increasing reliance on editing and varying shot size, the old tableaux style of static cameras and scenes played out in full, with the frame akin to the proscenium arch of a theatrical stage, began to look old fashioned, like the primitive efforts of early cinema and the elephantine grandeur of the Italian epics of the early 1910s. But even as American and British cinema was developing its grammar of film editing, in Paris, Louis Feuillade was playing with the possibilities inherent in tableaux filmmaking.

Feuillade found his style making scores of short comedies, fantasies, and historical spectacles at a pace that would make even D.W. Griffith blink. While Griffith was slowing down his output to craft and shape his stories and develop his narrative film grammar, Feuillade was cranking out shorts, serials, and short features at a breakneck pace, setting up scenes and letting coherence and chaos battle it out in his mise-en-scène. He wasn’t behind the times. His distinctive approach to filmmaking simply followed a different path. Where Griffith drove action through editing and turned to cutting as a defining element of his pacing, Feuillade was exploring the possibilities of set design, elaborate staging in depth, character movement, and surprise revelations, directing the audience’s attention within the frame and setting the rhythm of the film through its internal movement. His scenes played out in single takes with unmoving cameras (apart from the rare pan), yet he packed his frames with energetic movement and his labyrinthine stories with the fantastic and the unpredictable. In the years 1913 through 1917, there is no more creatively energetic, playfully inventive and entertainingly surreal filmmaking than in his wild crime serials: Fantômas (France/1913-1914), Les Vampires (France/1915-1916), and Judex (1917).

Based on the pulp adventures written by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, Fantômas chronicles the adventures of the cinema’s first supervillain. The heroes of the five wicked short features that make up this cycle are Inspector Juve (Edmond Breon) and the journalist Fandor (Georges Melchior) but the star is Fantomas, a thief, assassin, escape artist and master of disguises played with calm, stylish command by Rene Navarre. The anti-hero is very much the center of attention in this crazed masterpiece of secret identities, violent conspiracies and cliffhanger twists.

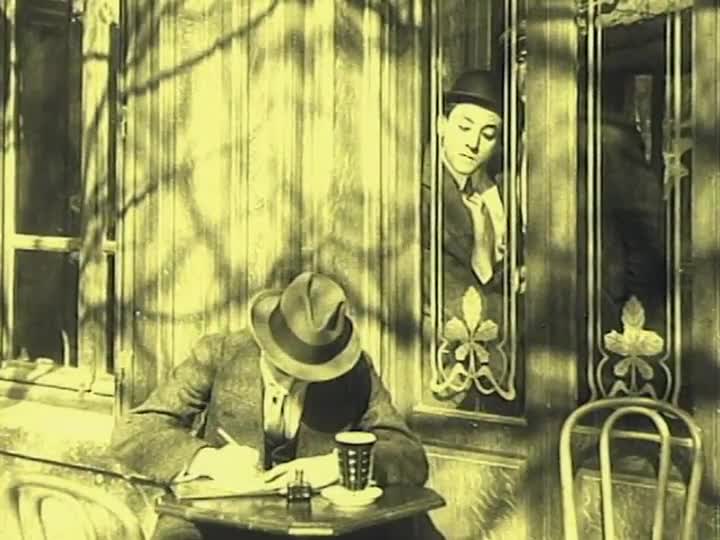

Embraced by audiences for its dime novel deliriousness and beloved by the surrealists for its mix of elaborate schemes and incoherent complications, it’s both archaic as well as strangely modern in style, pace, imagery and eruptions of the unexpected. Feuillade took his cameras to the Paris streets and shot at a breakneck pace. While other filmmakers tended toward the two dimensional, with action on a single plane and everything simply serving as evocative backdrop, Feuillade was playing with the interaction of foreground and background, or shifting the action from one side of the frame to another, drawing the audience around and through the image. Narrative coherence was of secondary concern to spectacle, surprises, and shocks, resulting in images and stories that are a combustible mix of visual control and narrative anarchy.

In Juve vs. Fantômas, the second chapter of the saga, Juve and Fandor follow the clues to waterfront, where wine barrels fill the beach. As they creep through the scene that could be a quaint landscape still life, it explodes into a surreal gang war as gunmen pop out of from behind barrels, firing at our heroes in the foreground and then setting fire to the scene. It’s a device that Feuillade uses throughout serials: letting the audience take in the stability and safety of a space and then tossing a narrative grenade into the middle of it. These films are festooned with secret passages and trap doors, allowing everything from the master criminal’s escape to a deadly snake attack on an unsuspecting victim to a booby trap wired to blow up any number of targets. Fantômas himself was ostensibly a master thief out for riches but as presented by Feuillade, he seemed far more interested in turning society upside down, flaunting his misdeeds in the face of the police, and acting as an agent of chaos simply for the sake of upsetting any notion of order. It’s easy to see why the surrealists embraced Feuillade.

Les Vampires is even crazier, a strange and wonderful masterpiece of criminal conspiracies spiced with wild twists and unexpected humor. The Vampires of the title are bloodsuckers only in the metaphorical sense. Think of it as a Masonic master criminal organization in black robes, a network as vast as anything Fritz Lang would concoct on the 1920s, that robs, kidnaps and murders their way through Parisian society while our ostensible hero, the intrepid reporter Philip Gueraude (Édouard Mathé), chases leads to expose the conspiracy.

The pulp plots of this episodic adventure are less mystery than chaotic thriller where nothing is as it seems and anything goes. When Philip discover and opens the hidden compartment above his bed, his pride turns to shock when he finds a severed head inside. And that’s just the beginning of this heady mix of secret passages, poison pen letters (with real poison pens!), disappearing bodies, and disguises galore. Major characters die suddenly and capriciously, victims are lassoed from windows and yanked into waiting sacks, society patrons find themselves suddenly walled in their mansion banquet hall and gassed by thieves so brazen they rob the place during a party!

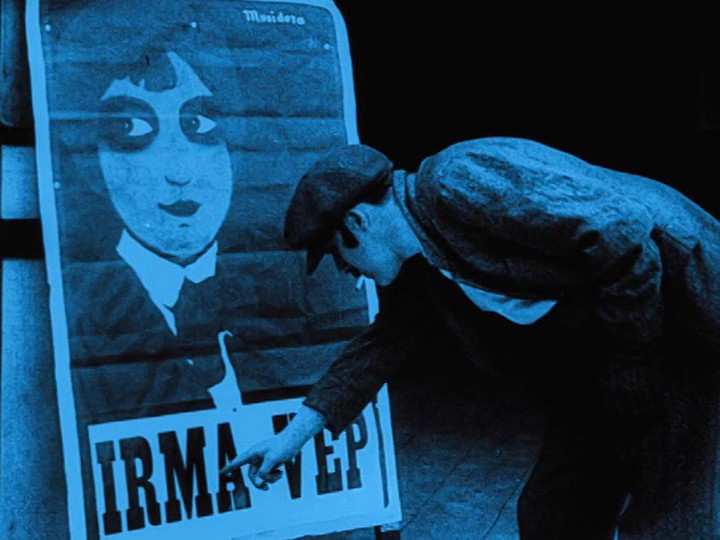

Shot on the run and often improvised in the volatile conditions of World War I France, this is less like a traditional American serial than a loose series of short films defined by the sheer unpredictability of its storyline. Feuillade wasn’t necessarily making it all up as he went along, but he was rewriting on the fly to take advantage of possibilities or accommodate an actor’s sudden unavailability, such as when the first Vampire leader was called up for service in the war. Feuillade simply had the character killed offscreen and replaced with a new Grand Vampire, but it also gave him the opportunity to turn slinky, sinister Irma Vep (French icon Musidora in a body stocking and black mask), the memorable chief henchwoman of the Vampires, into the grand dame of all silent movie femmes fatales.

And when a minor character named Mazamette (Marcel Levesque), who opens the film as Philip’s assistant and reappears in as a sad sack Vampire underling who repays Philip for a kindness, proved to be a hit, Feuillade brought him back as a sidekick, gave him a son (Rene Poyen, a star in his own right as Bout de Zan in a series of popular comedy shorts) and a small fortune, and promoted them into stars in their own right for a couple of chapters as a private detective team. Philip’s ultimate claim to heroism is that he survives it all. Given the body count of this production, that’s no small feat.

Les Vampires follows a dream logic that creates its own crazy, magnificent fantasy world. The lethal Vampires seem all the more deadly for their unpredictable killings and obscure intentions. It’s no coincidence that Feuillade names the series after the villains.

In contrast to those wild serials, Feuillade’s legendary Judex is almost classical in construction—it was scripted in collaboration with novelist Arthur Bernede and Feuillade kept to the script this time—and the story merges the roles of hero and villain into an ominous black-caped figure (a grim Rene Creste) on a mission of vengeance that borders on psychotic. Operating from a secret underground lair beneath a ruined castle, he punishes a corrupt banker by driving him virtually insane, and then dedicates his life to saving the banker’s virtuous daughter (Yvette Andréyor) from the machinations of a scheming femme fatale (Musidora, back for more femme fatale-ism). Also back from Les Vampires are Marcel Levesque as a private detective and Bout de Zan as a Parisian waif who becomes the plucky protector of the eternally-in-peril heroine’s young son.

Though not as surreal or as madcap as Les Vampires, this dreamy, moody twelve-part serial (thirteen if you count the prologue) is like an American adventure serial seen through a veil of opium. Motivations are purely emotional and impulsive and heroes can be as ruthless as villains. Feuillade’s imagery is also more controlled and carefully constructed as befitting such a deliberate mastermind as Judex, a man who plots and executes his vengeance with precision. At least until his love of the banker’s daughter soften his heart and his oath. You may miss the narrative bends and visual shocks of the earlier films, but in their place are more dimensional characters, vivid motivations, and a Gothic grace to the cliffhanger tales of dark heroes, anarchic villains, and innocents under attack.