Though in theory the successive wonders of VHS, DVD, Blu-ray and streaming should have made everything in the world readily available for home viewing, the truth is that plenty of fascinating films and filmmakers still fall through the cracks. A fine case in point is Eagle Pennell, a Texas writer-director whose brief creative peak occurred at a time when regional and independent American cinema were barely a blip on the radar. Like many truly unique artists, he wouldn’t/couldn’t fit into any commercial box and proved his own worst enemy in other ways as well. But the few works he left behind, some now available after decades of obscurity, are as welcome as meeting a best friend you never knew you had.

A star high school athlete from multigenerational Texan cowboy and ranching stock, Pennell acted like he was hot shee-it from early on. Leaving Lubbock for college, he arrived in Austin just as it was turning into the Lone Star State’s certifiable Coolsville, thanks largely to both homegrown musicians and new arrivals like country star Willie Nelson. “Austin was always the oasis in the Texas cultural desert….It was where everyone came to get a drink of water” says one interviewee in The King of Texas, a feature documentary about Pennell made by his nephew René Pinnell.

Its subject changed his name back then to suit his new persona as filmmaker/wildman. “Eagle” smacks of hubris, but as various surviving former associates in The King point out, he was indeed one guy who actually went out and made movies while everyone else in the local scene was just yappin’ about doing so. After dropping out of school, making a short documentary, and launching Austin’s first-ever film festival in 1975, he made the half-hour A Hell of a Note (1977).

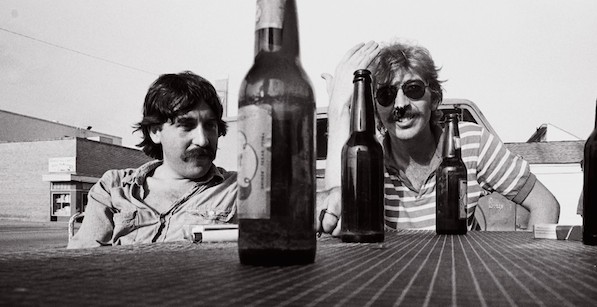

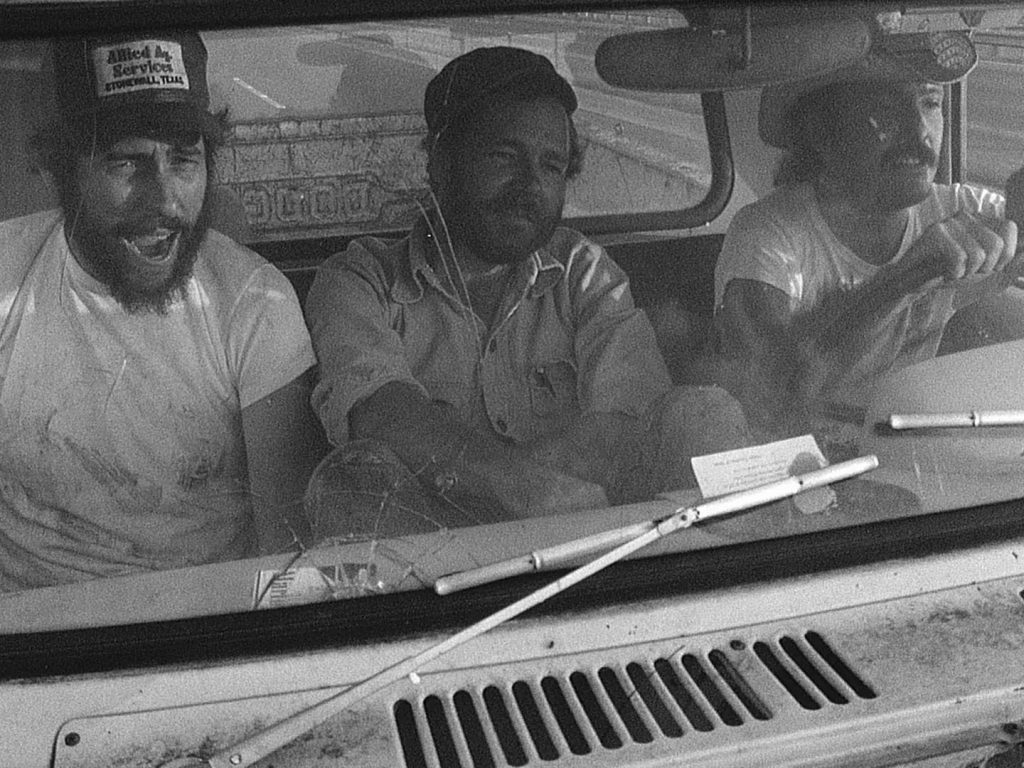

That cheerfully profane comedy—with a surprisingly sober conclusion—traced the antics of two good ol’ boys played by Sonny Davis and Lou Perryman. Early on, irked by their tyrannical construction foreman, they “done cussed themselves off another job,” and repair with a third coworker to a local watering hole to lick their wounds. Once that third party is dragged off by his irate spouse, the duo continue to party, eventually hitting another bar and hitting on some highly available young ladies. Unfortunately, one of them has a jealous ex—named Bubba, no less—who takes things in a surprising direction.

Made with little expectation of being shown to anyone beyond friends and family, A Hell of a Note instead created a minor stir, getting invited to a Houston festival where its ad-libbing leads were pronounced a modern-day Hope and Crosby. (Although a beery rather than stoned Cheech and Chong was more like it.) That exposure encouraged Pennell to make his first feature on a total budget of $15,000. Shot (like Note) in 16mm black-and-white, The Whole Shootin’ Match brought back Davis and Perryman in nearly identical roles—hapless best pals perpetually under-employed and on the verge of having their possessions seized by the bank. This is particularly a problem for Frank (Davis), who’s got a fed-up wife and one very mouthy son to support. (There’s a particularly hilarious scene in which this family unit goes to the drive-in and delivers priceless opinions on the art of filmmaking.)

But that doesn’t stop Frank and Lloyd from traipsing through various adventures surely doomed to do neither of them, let alone any loved ones, much good. A classic deadpan anecdotal indie comedy released six years before Jim Jarmusch struck arthouse gold with 1984’s Stranger Than Paradise, Match is considerably less mannered, funnier, more ambitious and touching than that certified hipster classic. It’s a gem that’s been neglected since 1978—when high-profile film critic Arthur Knight championed its virtues after its Dallas premiere. More significantly, when local resident and audience member Robert Redford subsequently saw it at what was then Park City, Utah’s U.S. Film Festival, he was purportedly so struck he immediately moved to rededicate that festival toward showcasing regional and independent American features. Such was the Sundance festival born, or so the story goes.

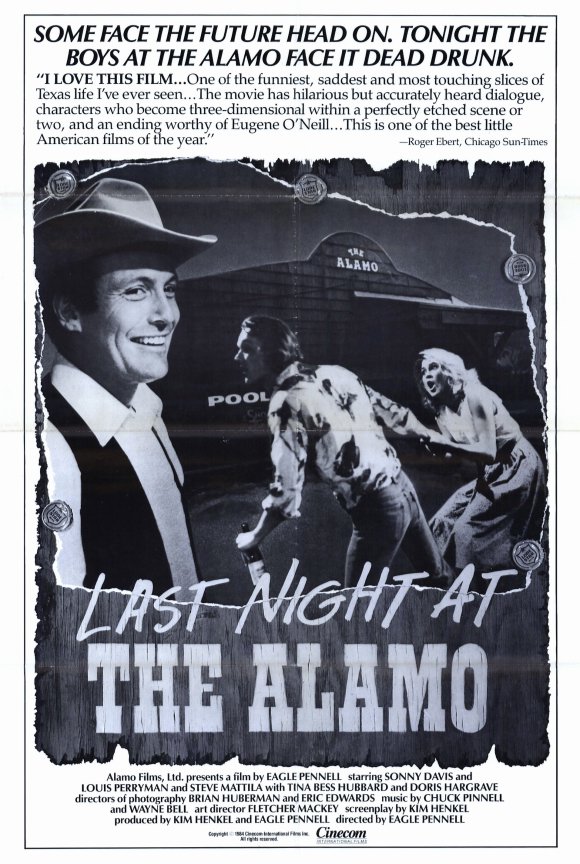

This attention got Pennell Hollywood offers. But being a rambunctious sort, he squandered his L.A. sojourn—and Universal Studios deal—on nonstop partying. By the time he returned to Texas to make Houston-shot Last Night at the Alamo, many former collaborators were already wary about working with him again. Yet despite whatever bridges had been burnt through ego and temperament, this 1983 feature about a beloved saloon on the verge of closure emerged as another salty delight that was praised nationally by the likes of Roger Ebert.

Still, it was another commercial non-starter. The later projects Pennell wanted to do could find no funders, and the ones he did complete were either for-hire assignments or microbudget films that apparently suffered from the absence of strong collaborators that had helped pull his relative successes into some sort of disciplined shape. (The Whole Shootin’ Match is credited as “a film by” both Pennell and co-writer/producer Lin Sutherland.)

As his opportunities degenerated, Pennell sank further into already well-in-progress alcohol and drug addictions. Once the last girlfriend attracted to his lanky bad-boy charms kicked him out, he was virtually homeless. Having said he never wanted to turn fifty, he indeed died—not a suicide, but simply from poor health—just days before he would have reached that personal milestone.

Maybe he was just naturally self-destructive, maybe no one could have “saved” him. But his early demise left Amerindie cinema short of one delightful pioneer.