Laura Poitras’ latest film, Citizenfour, is not simply a story of Edward Snowden leaking National Security Agency (NSA) documents or a polemic on the validity of state surveillance. It is surely those things, but more basically it is a document of our times. It depicts the current processes, tactics and risks of a certain form of adversarial journalism, of the current powers of information and secrecy in our culture and of the personal stakes one must assume to confront state power. It is a thrilling and anxious portrait that presents mundane moments alongside the exhilarating, confounding and frustrating ones. Regardless of what one may think of the political positions of Snowden and Poitras or reporters Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill, it would be difficult to leave a screening of Citizenfour without understanding their motivations more fully and empathizing with the risks they endured. It is a fascinating work that will be interpreted in a number of ways and will be a flashpoint precisely because it strikes at the personal and emotional heart of many tensions and contradictions in our society—between liberty and security, law and secrecy, state and representative power.

By now you’ve surely read a few profiles on Poitras and learned that she is a filmmaker working in the tradition of cinéma vérité. That is, she captures events on site as they unfold in real-time and uses that as the primary footage to create her work. She is acclaimed in filmmaking and journalistic circles. She’s won a Peabody Award, is an Academy Award nominee and received a MacArthur Fellowship, also known as the “genius grant.” And note these accolades all came before she was contacted by Snowden in January, 2013. Following that, work she contributed to (in the Guardian and Washington Post) received the Pulitzer Prize. And, as was covered in a lengthy profile in the New York Times in 2013, she’s also controversially been accused of having foreknowledge of an ambush on U.S. troops and not warning anyone. For six years she was on a government watchlist and was stopped and detained at borders over forty times.

Citizenfour completes a trilogy that she has made about post-9/11 America. The first in the series, My Country My Country (2006) covers American-occupied Iraq during the lead-up to the January 2005 elections by focusing on a Sunni candidate, Dr. Riydah al-Adhadh. The second film The Oath (2010) investigates the human and political effects of Guantanamo Bay Prison primarily through the life of Osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard and former Guantanamo prisoner, Abu Jandal, as he tries to move ahead with his life in Yemen. The final film began as a documentary investigating surveillance. A short Poitras made titled The Program, posted as an Op-Doc on the New York Times’ website, gives a sense of where that film was originally headed.

But her contact with Snowden changed the entire direction of her work on the subject. She, along with reporters Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill, flew to Hong Kong to meet their anonymous contact and, in vérité style, Poitras captured the encounter. The vestiges of Poitras’ earlier work on surveillance survives and includes whistleblower William Binney and computer security expert and WikiLeaks member Jacob Applebaum at various moments. But a large part of Citizenfour takes place in a nondescript Hong Kong hotel room just as Snowden, Greenwald and MacAskill are about to publish secret NSA documents. And, that’s really the beauty of the movie. For a great deal of the film’s time, we are presented with a mixture of chillingly ordinary conversations with the implicit knowledge that those involved are about to make very powerful enemies.

I was able to sit down with Poitras, and I first asked her how she saw Citizenfour in the context of her post-9/11 trilogy.

Laura Poitras: I started this body of work in response to the occupation of Iraq. And, I think that the motivating force was an attempt to understand the human consequences of the war on terror and U.S. policy, post-9/11, and not to just step back and have political debates, but actually go to places where we can understand it from an on-the-ground perspective, and understand these big issues through the lives of individuals who have direct experience with them. I think that’s a valuable thing. It changes the kinds of information that we have on the so-called ‘war on terror.’

Before I went to Iraq, I would look at the front page of the New York Times and what I would see are ‘body counts.’ You know, ‘230 people killed in a car blast.’ Every day would have a body count. None of these bodies had names to go with them. I wanted to understand what these body counts actually mean from a perspective of ‘Who are these people?’ What I try with my filmmaking is to provide information that communicates on an emotional level. I’ve tried to do that by telling narratives through individual’s trajectories.

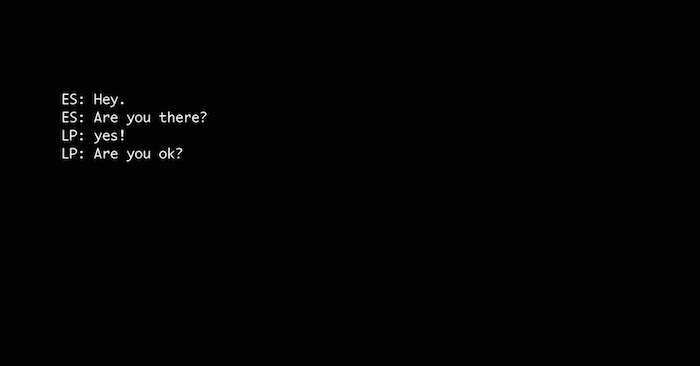

With My Country, My Country, I think I began with a somewhat naïve perspective thinking the pendulum is going to swing back. Then I saw, OK, Guantanamo is still open, so then I made that film [The Oath]. And in 2006, what I was documenting pulled me into things. I was put on a watchlist and I was being stopped at the border. And, that oddly leads to Citizenfour. Being stopped at the border led me to learn how to use tools of encryption which then prepared me for an anonymous person knocking at my door saying, ‘Hey do you have an encryption key?’

Sean Uyehara: This idea that the stops at the borders led you to learn about encryption, which, perhaps ironically, led you to being the person that Snowden contacts seems emblematic or metaphoric for one view of post-9/11 activity by the US government. It’s supposed to corral these outside forces, but instead it seems to have the reverse effect of galvanizing forces against us. At least, that’s how I read some of what you are saying.

Poitras: Those are two separate things. One, yes, there is an ironic narrative that one of the unintended consequences of being put on a watchlist for years is that I became pretty good at using technology that helps me to protect the sources that I work with. And, then there’s the other question, and I do believe that in the name of security, of making us safer, that we’ve made a whole lot of people more angry with us than they were before. With things like Iraq, Guantanamo and drone strikes, I think that the global reaction is more anti-American sentiment, not less. And, I don’t think it leads to more security; I think it leads to less. And, I think that what we’re seeing that, for instance, what’s happening in the Middle East now is partly due to the unintended consequences of the failed Iraq war.

Uyehara: What impact do you want your film to have? Do you just want people to have the knowledge it contains? Do you want them to act on it? What’s your ideal scenario?

Poitras: I spend a lot of time making these films, and I take a lot of risks. I don’t make them as a means to an end or to elicit any particular action. I want to express something about the human condition in the particular history we find ourselves in in a way that has meaning amongst current audiences and hopefully into the future. Novelists don’t write novels because they want their readers to boycott…whatever. It’s the same with filmmaking. Yes, documentary filmmaking engages with real issues. And, I do think that this kind of surveillance poses a threat. There are many people who say that eloquently in the film. But, in the end, I think I am documenting the fact that somebody, a young person, would take a risk, because he felt that these programs and capabilities pose a threat and this should be something that the public debates, that this should not be happening in secret.

Uyehara: Picking up on this idea of the contemporary ‘human condition,’ I was struck by the monumentality of the moment, trying to decide what to do next. It feels like there is this precipice that you are looking over. I read somewhere, I think it was your collaborator Katy Scoggin who said that when she was looking at the footage in the hotel room that it was as if she was looking at someone who was ready to commit suicide. And I wonder is that part of the current human condition—that if you want to confront any of these powers then you have to prepare for your life to be irreparably altered?

Poitras: I think the quote was from Mathilde Bonnefoy, who is my editor, not from Katy. I wouldn’t describe it as suicidal rather it’s more about one’s willingness to accept whatever consequences. Snowden felt that the importance for the public to know what the government’s capabilities are was worth the risks. He articulates that very well when he says that he remembers how the Internet once was as a force for good and not a force for surveillance.

But it was an extraordinary moment. Because he made the decision that he wasn’t going to conceal his identity, it allowed me to film someone who had basically reached the point of no return. He had crossed over a line and didn’t know what the consequences would be. And, there was a sense for all of us that there were real dangers and that we would be angering very powerful people.

Uyehara: I guess what I am getting at is that from my perspective, I feel like you are in a different world than me. To say it out loud sounds incorrect or surreal, but you’ve decided to confront this power, so you’re on that other side and I feel like there’s an inertia or inevitability that people like me feel when they face such powers, ‘Well, what can I really do?’ It seems massive. And, I feel like that is in the film as well—that you are taking on not only the U.S. government but governments in general and corporations as well. It’s overwhelming.

Poitras: I think a different way to put it is that actually very ordinary people can challenge such forces. Clearly, Edward Snowden took enormous personal risks. And, I’m not saying that there aren’t dangers that I’ve felt doing this reporting or that Glenn has faced. We’re very aware of those risks. You know we were just doing what we think is right. One of the powerful things that has come out of this is that we have been able to make an impact. People’s consciousness about state surveillance has shifted. We’ve put on the table a moment where people can decide which direction to move in. Working on this definitely felt more risky and dangerous than working in Iraq. I feel like the forces are more powerful even though there aren’t bombs going off. They are more abstract, they are harder to know where they lie. It hasn’t been without a certain amount of trepidation and fear.

Uyehara: You talk about putting information on the table, giving people the information they need to make an informed decision, and, I’m thinking about things like polls that are taken that show that a majority of Americans are for drone strikes. What would you do if people are given all of the information out there about surveillance if they then said, ‘It’s OK. I don’t mind being surveilled.’ If it were truly open and the people decided, ‘I want surveillance,’ then, is that OK?

Poitras: Actually not, because we have a Constitution which protects our privacy. We have a Fourth Amendment. So, whether or not someone wants to relinquish their rights tomorrow, their rights are enshrined. And they are enshrined for the people living today and for the next generation. If we want to change our laws then we have to go through a legal process. It’s not just about public opinion to determine what our government does.

Uyehara: I know so many people, and you’ve heard this, who say, ‘Well, I don’t have anything to hide and I still want to use the Internet, so well….’ and they just throw up their hands.

Poitras: What if it was announced tomorrow that the government just wants to turn on all cellphone and laptop camera—just turn them on all the time, you know, because you’ll be safer? I think most people would not be OK with that. (Laughs.)

Uyehara: Well, I dunno. I think we’d have to take a poll…. What question do you wish that you were asked more often?

Poitras: There haven’t been many questions about Glenn and I working together. There’s been a lot of questions about Snowden, but working with Glenn has been really powerful. We were colleagues before, but we didn’t know what would happen working together. It was completely untested.

Uyehara: Are you talking about The Intercept [the online publication founded by Poitras, Greeenwald and Jeremy Scahill] right now?

Poitras: Not so much the Intercept, but on this story in Hong Kong, how we worked together and how our strengths complemented each other. We were friends and colleagues and shared some similar views, but to be thrust into such an intense situation with people who you’ve never worked—both with Glenn and Ewen MacAskill, it was actually quite extraordinary to witness that. To see the reporting they did and their openness in allowing me to film. How Glenn managed to fend off huge attack after attack from the very beginning. His ability to articulate in powerful terms why these issues matter. It was really a unique kind of collaborative experience.