The action movie offers a consistent and under-acknowledged pleasure. If most of these films concern restoration of status quo, and they do, then there’s the thrill offered by the existence of the order itself, unperturbed as its own state of being, in addition to the obvious thrill of the choreographed chaos that ensues once said order is imperiled. Order has become a point of fetish in contemporary action cinema, perhaps to an unprecedented degree. A pivotal part of the action film’s appeal to audiences resides in the first act, in which we’re presented with its stylized version of the quotidian. It’s this first portion, which usually lasts twenty or thirty minutes, that establishes a fantasy that audiences are reluctant to abandon, and this reluctance fosters an empathy with the heroes, who’re scrambling to reinstate paradise after bad guys steal a plane or someone’s important daughter.

Because paradise is, indeed, what it is. The first act revels in the good guy’s awesomeness. If the protagonists are young, the first act revels in daredevilry, often bar and bed-hopping, that establishes, in the film’s moral schematic, a callowness that’s to be corrected before the end credits, not that anyone really believes or wants that. If the leads are older, say, in their fifties, at least, the first act is ordered around the assertions of the glory they’ve won for themselves in the past, presumably during that time when they triumphed over said callowness. The heroes are usually consultants or enforcers of some vague kind, and this information serves two purposes, one literal, one quietly, shrewdly metaphorical. Literally, “consultant” is often a euphemism for whatever profession, with which the hero once excelled, that involves a skill set necessary for killing bad guys, or that’s responsible for angering the bad guys to begin with, or, often the case, both (professions include assassin, military something or other, agent for CIA, FBI, or something else made up for the purposes of the film). Metaphorically, and more importantly, these guys appear to be retired, living a dream of walking a perpetual victory lap as reward for decades of devoted, and unseen, work.

It’s this metaphorical heft that explains the present currency of the aging-dude action film, and the fashion with which it has allowed Liam Neeson and Denzel Washington, the genre’s current undisputed all-stars, to flourish. The young-dude action film, with which Tom Cruise continues to specialize despite his age, and with which Chris Pine is attempting to specialize, is losing its luster. Audiences don’t want heroes to learn a lesson, however trivial and obviously de rigueur it may be. They want already actualized heroes to unwaveringly teach someone else a lesson. Audiences have grown less interested in the chaos of the action film (Mel Gibson’s cinema is impossible now); they want the stability of that first-act older-dude retirement package, which shows, first hand, the fruits of the self-actualization that so many movies (of any genre) imply to be ripe for the hero’s (read: our) picking at the end of a picture. The older-dude retirement movie allows us to enjoy that end, right at the beginning, and then return to it after a perfunctory endurance test has been passed in the form of thwarting a bad guy’s invasion.

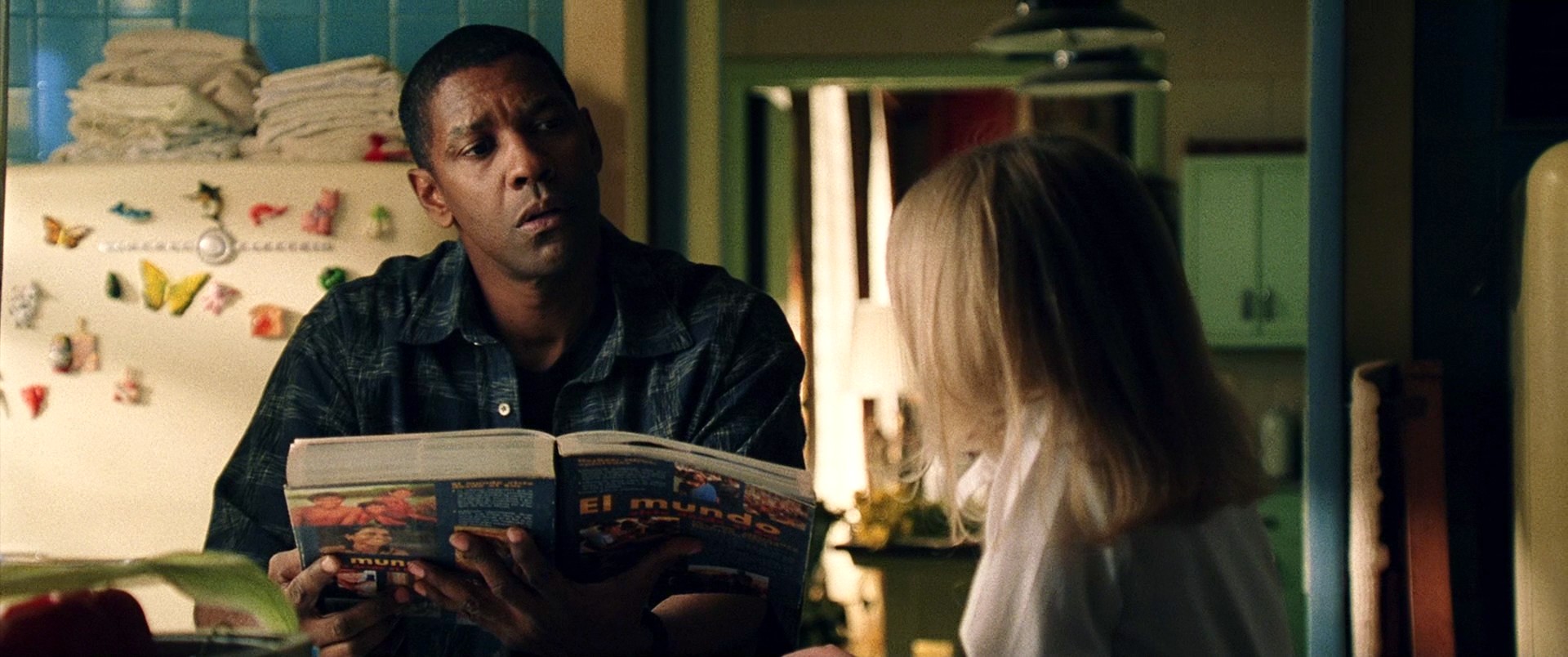

Neeson and Washington’s present run of films offer a vision of imperiled first-class comfort largely unknown, though desired, by paying audience members. In Taken, you respond less to the girl’s kidnapping than to the distress of knowing that Neeson will have to put the brakes, temporarily, on grilling out with his badass former ops buddies, or on body-guarding young worshipful female celebrities, or on trading moony glances with his gorgeous newly-moneyed ex, who is, unsurprisingly, not over him (tellingly, her replacement beau is played by Xander Berkeley, the Ralph Bellamy of modern action movies). In Man on Fire, you’re disappointed to witness the interruption of Denzel Washington’s bond with Dakota Fanning, though you might be truly disheartened to see the film move out of that rarefied estate where the former weathers the pregnant glances of many a woman, while referencing his past as a legendary whatchamacallit with maximum levels of appropriately melancholy movie-star machismo.

All major Neeson and Washington vehicles, going back to the cementing of their present personas (in 2008, for Neeson, with Taken, and in 2004, for Washington, with Man on Fire, respectively), feature prolonged first acts in this vein, which revel in women, adoring or resentful children (both kinds triggered by the hero’s career prowess, and thus, congratulatory either way), money (they might not have it, but they don’t need it either, as these are Spartan men of no debt, which is to say that they have both the masculine glamour of having money as well as the equally masculine, and artistic, glory of not having it), and, above all, appreciation, of which they experience in every possibly known facet. That’s what all these spoils ultimately yield, and what people pay to experience: vicarious adulation in a culture that frequently asserts their importance to them without ever proving it.

The characters these actors play are plagued by problems, even common problems, such as alcoholism, or divorce, or familial estrangement. But they suffer these problems with the heightened aura of a dime-store pulp hero: their stubble is perfectly imperfect, their whiskey eyes adorably pleading, their self-absorption but a symptom of their great gifts that must be wrestled to the fore to serve the greater good (ultimately themselves, the masses being but an abstraction). A Liam Neeson or Denzel Washington drunk is the kind of drunk that real drunks think, or hope, they resemble as they tumble further into the recesses of their internal darkness. Even more somber, superficially less escapism-driven vehicles, such as The Grey or Flight, feature plenty of that all-important first-act ego massage to assure us that, while these gods have fallen, they are gods nevertheless. (A tendency that’s particularly amusing in Flight, a vivid, well-acted drama that can’t always discern between an alcoholic’s reality and their self-flattering dreams of occupying the center of everyone’s universe.)

It’s interesting to watch Neeson and Washington, two talented, almost ludicrously powerful actors, navigate similar material in entirely opposing fashions. Their power over audiences, their primordial maleness, is similar, but they handle a key and tricky element of the perfect aging man icon differently. Action men, whether they’re John Wayne, or Charles Bronson, or Arnold Schwarzenegger, or Neeson, or Washington, are only as good as their ability to project audience-endearing humility as necessary counterpoint to the prevailing entitlement of the films’ vigilante restoration narratives. Wayne, with the exception of Rio Bravo, wasn’t very good at projecting this particular emotional register, and his best films often traded on that insincerity. Bronson was exceptional at it, and Schwarzenegger makes for about as poor a modest hero as any the genre has produced, but Neeson and Washington are virtually unparalleled in selling their audiences characters who’re contrite for past acts that everyone knows are probably disreputably impressive, and that have got them to where they presently are (which is, lest you need reminding, a stable realm of unchecked admiration and financial certainty that’s eventually obligatorily endangered by a baddie).

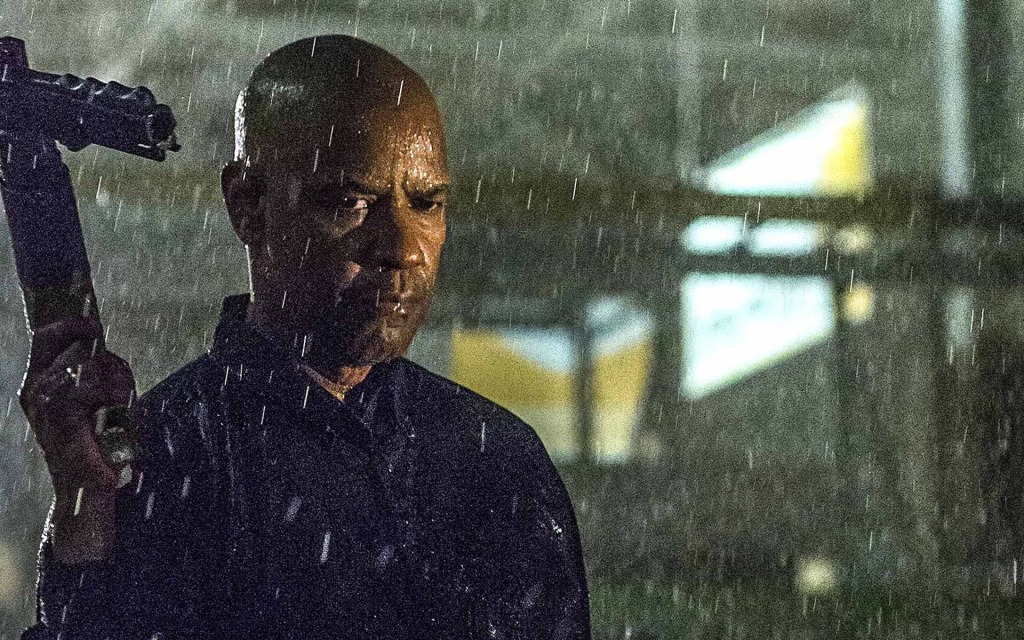

Neeson projects sincere longing and heartbreak, which particularly fits his current film, A Walk Among the Tombstones, as it’s haunted by a legitimately awful, unglamorous trauma. Washington presents holier-than-thou sanctimony with so little sense of sentiment, particularly in the current The Equalizer, that you are fascinated and repelled, rather than moved, by him. Neeson earns your respect directly and conventionally; Washington accesses it through the back door, after taking the long way home, so to speak. Neeson’s power as a performer is laced with pathos; Washington’s power is a study in unchecked ego that often eclipses the films’ usually otherwise modest intentions. Neeson bolsters his films, as their strongest element; Washington operates as a self-encased atom that exacerbates his films’ creepiness, causing you to wonder how much of their implied fascism is accidental / incidental.

The commonality, though, is the solicitation of iron-clad dignity for these characters; however the actors go about earning it. They represent terra firma, a root in unquestioned, unmoving past-ness, in a culture increasingly marked by signs of erosion, instability and even evolution, embodying an attainment of comfort that, perhaps, will not be available to Generation Y and the Millennials at a similar point in their lives. And, maybe, that’s really why these first-act pleasure cruises are so satisfying to audiences, maybe more than ever: because they don’t quite take that stability for the given that they might have twenty or thirty years earlier. These actors launder our insecurities, funneling them back to us, cleansed, as theoretically unsullied fulfillment.