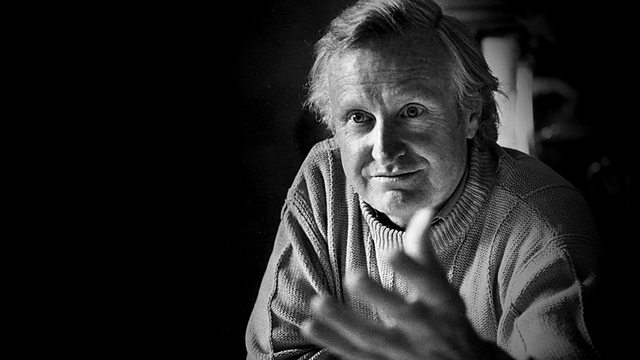

Writing an introduction for the films of John Boorman is to recite a canon of modern cinema classics. From Point Black to Hell in the Pacific through the monuments of Deliverance and Excalibur and the offbeat and beloved Zardoz and The Exorcist II: The Heretic, the filmmaker takes his audiences by the skull and pulls them directly into his extremely visualized film scenarios. Having just completed what he feels may be his last film, Queen and Country, a sequel to his five-time Oscar-nominated and Golden Globe-winning Hope and Glory, the eighty-two-year-old director is making the rounds for his latest picture with his producer Kieran Corrigan, their eighth project together. Mr. Boorman loves, lives, eats and breathes cinema, a passion that includes performances by his own children, and a feature documentary by his daughter Katrine on her father, Me and Me Dad. And now, let us meditate on this at second level. . . .

Shade Rupe: It’s wonderful seeing some of the characters from Hope and Glory again. You’ve indelibly created so many over the years. Every time I see one of your movies, no matter what the locale, it’s very, very easy to fall into the world that you’ve created.

John Boorman: Oh, that’s great. Good to hear.

Rupe: Point Blank basically takes place in our world yet is so fantastic in the way it’s presented. I just watched Deliverance again, and even there you take an audience who’s used to sitting in a city and bring them right into that wooded environment.

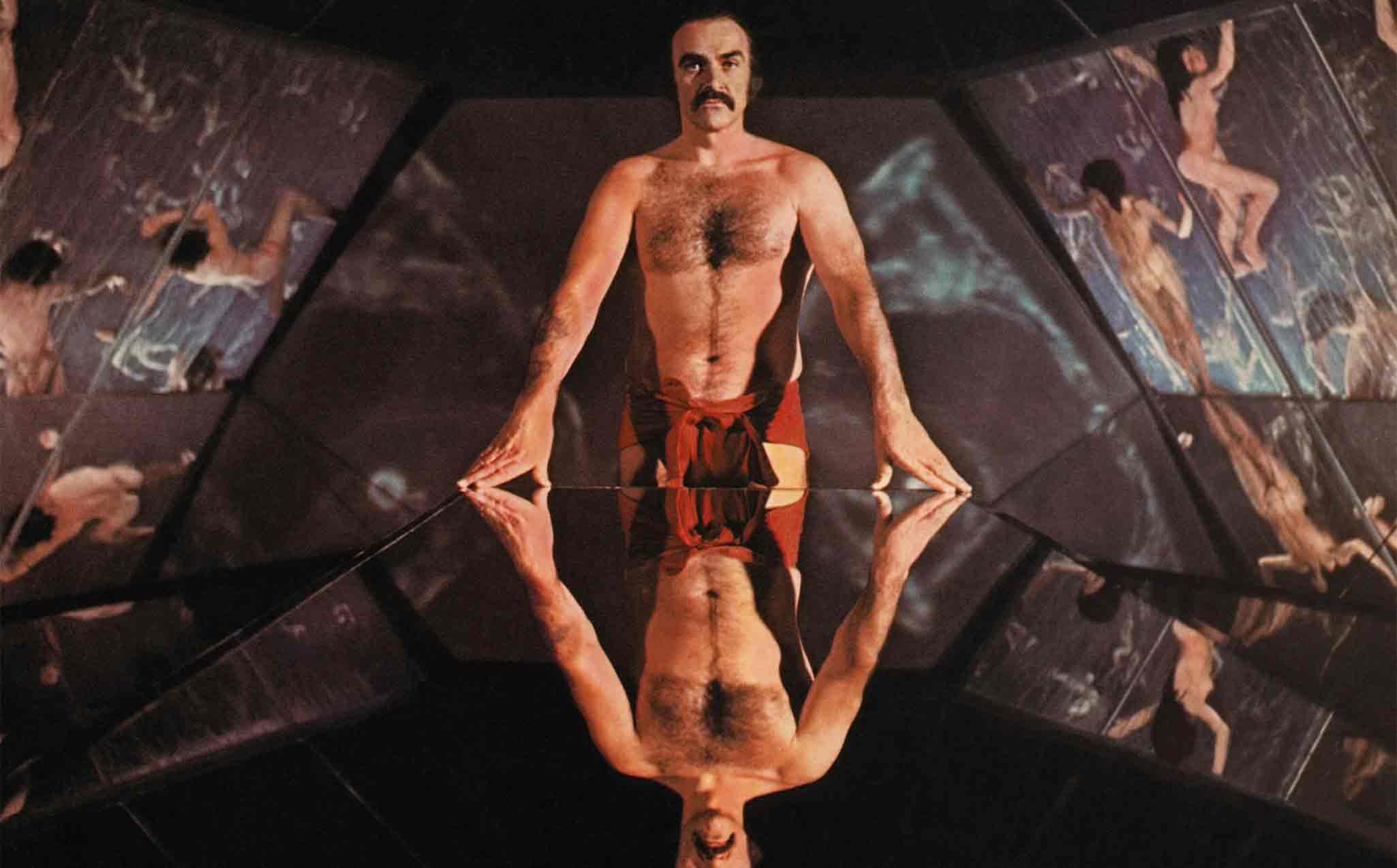

I find Zardoz equally as easy to fall into. It’s one of my favorite films and has been since the day I saw it on a double bill with The Man Who Fell to Earth.

Boorman: That’s good to hear because it’s a bit of an orphan but it has a very loyal band of followers.

Rupe: When you were making a film like Zardoz, which followed up a film like Deliverance, which is right here, on the planet, in the woods …. what was going on with you at the time that you made Zardoz? How were you expecting that film to be received?

Boorman: Well, I think that I was able to make it because of Deliverance‘s success, and I’d had it in mind for a while. Along with the notion that the rich were getting richer, the poor were getting poorer, and the rich were living longer than the poor in a worldwide sense. So, I just projected that forward in time, and then speculated on what might happen. I think I would not have been able to make it unless Deliverance had been such a success.

Rupe: Had you been pitching Zardoz for a while, or did you just keep it ready for when it would make sense to bring it to life?

Boorman: No, I didn’t try before. I had the idea for some time; and after Deliverance, I sat down and wrote it, and presented it first to Warners. They wouldn’t do it. Eventually, I did it with Fox.

It was based on you could say a political idea, a sociological idea. But then I then let my imagination roam over what might just come about. I just really pushed this trend into the future, and figured out what might happen. Of course, medicine has extended the lifespan of humans. And if you push that further still, you could get to a point where they would overcome death, so it’s possible to live forever, and what are the consequences of that? That was my thinking.

But I think, today, when you would do science fiction today, there’s always a danger of falling into the arms of CGI. And because of what CGI is, you can create almost anything, it becomes a trap, really, rather than a solution.

Rupe: People now rarely think about how can we convince the audience of this other world. How can we bring them into this other world by speaking directly to them? Instead, we’re just going to show them special effects. You don’t feel like you’re there because you’re not….You can turn up the volume on clinging swords, but in Excalibur, you can really imagine what it would be to wear a heavy piece of armor and go into a battle. Even the magic in that film is something you just fall right into. You can really feel Uther, his need for Ygraine is so strong. You, as the viewer, you’re watching the horse gallop on smoke. You don’t need a computer to do that. The actors did that. The actors let us know.

Boorman: That’s right. All the effects in that film were done in camera. Nothing was done at all in post, all done in camera. In the old traditional ways of doing effects there’s something that it gives you what you don’t get from CGI.

Rupe: Hope and Glory carries many of your memories and what you experienced as a kid. A war film will usually be focused on the frontlines or the soldiers in a battle and here’s one of the few times where we’re seeing the effects of war for people who are at home and not fighting. I love the sequence with the barrage balloon. It’s so unusual to imagine what it would be like to have something like this happening all around you but also that family in that film is so wonderful that you can almost imagine them as your own brothers and sisters, or father, you want to have your own dad teach you the googly.

Boorman: Yes. It was based wholly on what I remembered as a child in the London Blitz. It was very deeply felt, and it was also about my own family, so, I have a great affection for that film. And now, in Queen and Country, the boy gets a little bit older.

Rupe: At the end of Hope and Glory the kid exclaims ‘Thank you, Adolf!’ and we feel that the experience of World War II was over but in actuality continued with the Korean War for many British people. It’s not something that we were made aware of here in the States. Since Hope and Glory was your story that you were telling in 1987 of your youth, what made you needed to continue the story twenty-five years later of what happens with that family ten years later?

Boorman: After I made Hope and Glory, I had in mind to do two further films. One about my time in the army at eighteen, and another one about my mother, when she was younger, and her sisters when they also spent time on the River Thames at Shepperton. I never got around to doing those as other projects intervened but I always wanted to do something about my brief army career. And so, coming to the end of my filmmaking career, I thought I’d better do it now or I’ll never do it. And that’s how I got to the point to do it.

Rupe: What was Broken Dream? Caleb Landry Jones, who plays Percy Hapgood, was attached to that project at one point.

Boorman: That’s how I came [to be] in touch with him, because of that project. It’s a long cherished project I’ve had for years, and I’ve made several attempts to make it but without success. The reason is that people see it as an art film but it needs a bigger budget than an art film is able to get. So it always falls south of that problem. I’ve been close to production on it a couple of times, and then it fell because of the lack of money. If you’re working with independent films outside of the studio system, the money is always very fragile. Often, lot of independent movies collapse a week or two before shooting. And that happened to me with Broken Dream.

Rupe: How much of Queen and Country is autobiographical then?

Boorman: Oh, a great deal. For instance, the story of my first cigarette, a strawberry-flavored cigarette. That was exactly how it happened. Also, the character played by David Thewlis, Bradley, was exactly that character. In fact, every time David Thewlis came on the set in uniform, I get a little freeze of fear in my memory. He’s an extraordinary actor, David Thewlis, and he said that he just understood that character perfectly.

Rupe: And, how much of the character did you give him? Did you sit around and just tell stories of that character, or did you just give him enough or just give him the script and he just knew how to create it?

Boorman: Well, this character was I think very clearly defined in this person, when I gave it to him and he said to me, ‘You know, most films I do now, I have to work on the dialogue to make it work,’ and he said, ‘but I wouldn’t alter a comma of this. It’s so perfectly defined,’ and that’s what he did or didn’t do.

Rupe: And then with your two actors, Callum and Caleb, had they both seen Hope and Glory?

Boorman: Oh, yes, indeed. Absolutely, and studied it many times and we did a long rehearsal period with the two of them because it was so important to keep their relationship working. And you know Callum had very little experience but he has a lovely quality of shyness and truth about him which I was very attracted to.

Rupe: You’ve now made two directly autobiographical feature films, years apart, and your daughter Katrine has also made an autobiographical documentary with Me and Me Dad.

Boorman: That’s right. And I did another autobiographical film for the BBC. It was a television film called I Dreamt I Woke Up. John Hurt was in that too. He played my alter ego. It was a lot of fun, and it’s very autobiographical. It’s very much about place where I lived and the house that I lived in. It was just partly documentary and partly fantasy in a sense that some of the characters from my films, like Merlin, make an appearance, but it wasn’t Nicol Williamson because he had departed the earth by the time we made it, unfortunately.

Rupe: How did you meet Kieran Corrigan?

Boorman: Well, when I came to Ireland way back in 1970, Kieran was a brilliant young accountant and also a lawyer, a barrister. And so, we got together. He helped me on a lot of things, and little by little, our relationship developed. He is a really very bright guy. He gets involved in all kinds of things.

Rupe: Did he suggest I Dreamt I Woke Up or is that something you came up with together?

Boorman: No, it was suggested by a producer at the BBC who asked me and several other directors to make a film about our own environment, our own place. I made it and it was a lot of fun. It’s very nice to make a small film because there’s much less stress involved.

Rupe: You and Kieran have taken to each other very well as you have so many projects together including Queen and Country. Do you feel you have more stories of your life that people need to hear?

Boorman: Well, there was one other autobiographical story that I thought about, that I haven’t really written into a script yet or anything. When I met Lee Marvin, and how our relationship developed into Point Blank, was really quite extraordinary. I met him in London. He was making The Dirty Dozen, and someone had given us a script. We met and he said, ‘What do you think of this story?’ I said, ‘Well, I think it’s terrible work, really.’ He said, ‘Yeah, well, so do I. What are we talking about?’ I said, ‘Well, characters are interesting.’ We met a few times and gradually I came to realize that this character in Point Blank who is really killed at the beginning, shot at the beginning, and then somehow comes back to life looking for his money which is in a sense a search for his own soul, his own humanity. And, Lee’s war service brutalized him. And for him, acting was a way of trying to re-find his humanity.

And so, as I developed it, this story became the story of Lee Marvin in his quest to recover his spirit, his soul, his humanity. That’s what gave the film its power, in part. I’ve often thought about doing a film, not about making Point Blank, but what led up to it. But I don’t think I’ll ever be able to do it. I mean, I’m eighty-two years old now. I know that Manoel de Oliveira just completed another one but. . . .

Rupe: Clint Eastwood just directed American Sniper.

Boorman: That’s right. He’s older than me.

Rupe: Nicol Williamson’s Merlin is so singular on the screen. His cadence, his delivery is incredible. Did he create those strange ways of speaking those lines? Did you create that together or was that completely Nicol?

Boorman: I saw Nicol’s Hamlet, and he had those cadences in Hamlet. And that’s why I wanted to cast him because of that way of handling the cadences of dialogue. I made it for Orion, and they had made several films with Nicol Williamson, all of which had bombed. So, when I wanted to cast him, they said, ‘Look, cast anyone in the world you want but not Nicol Williamson.’ I tried to think of someone else in that role and I kept coming back to Nicol and I said to the Orion company, ‘I don’t care what you say, I’m casting Nicol.’…. He had this wonderful eccentricity. It’s so easy for the character Merlin to sound really conventional and old. He revitalized the character brilliantly.

Rupe: How did you come up with the Charm of Making?

Boorman: That’s interesting because actually it’s old Irish. What it’s saying is it’s summoning the dragon’s breath and it’s expressed in old Irish which is not the Irish that is spoken today but it has the same equivalence as ancient Greek does to modern Greek. And so, it was sufficiently obscure to work for the picture.

Rupe: Everything that came from that film is so strong. Where did the idea for Merlin’s helmet, his headwear, come from?

Boorman: Originally, I wanted Nicol to shave his head, and he agreed to do so. And then, at the last minute, he said that he didn’t want to shave his head, he was afraid his hair wouldn’t grow back. And so, this guy, Terry English, who was doing the armor, he came up with this skull cap made of metal and he made it so it fitted to Nicol’s head and that’s how we came to it. And it’s probably rather better than my original solution, because he was very distinctive. I’ll tell you what, the limitations of film often give birth to some of its best ideas.

When I edited, with Walter Donohue, the series called Projections, in one of the editions I sent out a questionnaire to directors all over the world, and I asked, ‘What film would you make if you have unlimited time and money?’ Most of them were horrified at the thought. We spend our lives trying to get the money to make a film, and then given unlimited resources, most of them threw up their arms in horror because it is the limitation that often defined the film.

Rupe: If you want your vision to come across, and you have that need and desire, you will figure it out if it’s strong enough. Bringing the audience into that world again, that’s something that you just have this magic wand built into your fingers of doing. You used to meet a filmmaker and go, ‘Oh, how’s your new film going?’ And you talked about your ideas and how you and your actors and crew brought them to life. Today, everyone says, ‘What did you shoot it on?’ ‘Oh, I shot it on the Red.’ ‘Oh, really. Well, I used …’ And they’re talking about the technology rather than the film.

Boorman: When I’m pulled into that controversy, I will say, ‘What matters is what you put in front of the camera and not what the camera is.’

Rupe: Yes, and what is behind it. I don’t think Nicol would have created that on his own. He needed John Boorman to make that happen. There’s this synergy that happens on the set and I think it’s actually better not to think about, ‘Oh, I have to put this plug in here and flick the switch.’ It’s more like, ‘Hmm, how were the shadows creating this view here?’… As far as budget goes and releasing patterns goes with Hope and Glory, how closely did that come to what you wanted it to be? And with Queen and Country, how closely has that come to what you wanted that film to be?

Boorman: Well, Hope and Glory had quite a decent budget because we had to build that street and then evoke that whole period of wartime. And I think that Queen and Country probably has the lowest budget of any film I’ve made. I would say, as you get older, it should get easier and you can spend longer shooting them, but it doesn’t change the work in my case.

Rupe: Well, how many clocks did you have to make when you were throwing them out the window? Hopefully, the budget didn’t go there.

Boorman: [Laughing.] Well, no, I had someone catching the clock.