Jem Cohen, with his range of experimental documentary, short films and features blending fiction and documentary, defines the independent filmmaker. His alt-culture-interested films explore life in the margins, maverick places, lost souls and unwavering autonomy. Fittingly, he’s racked up an Independent Spirit Award, as well as the 2013 Persistence of Vision Award at the San Francisco International Film Festival, well deserved honors, the titles of which so accurately reflect the artistic voice and DIY approach that Cohen’s honed over the last thirty years. On the eve of the theatrical release of his latest feature, Museum Hours, Cohen took time to answer some questions about that film, and his approach to its making.

Keyframe: First of all, Museum Hours is a beautiful film. You nail a sense of dislocation and memory. You address how art can capture an essence of time and shift while calmly touching on big themes of mortality. How did the project begin?

Jem Cohen: Well, it all began with a childhood of being dragged to art museums, not that I always appreciated it then. More specifically, I spent a lot of time in Vienna in the last six years, mostly because one of my very favorite film festivals—the Viennale–is there and has screened my work and commissioned some projects. Frankly, it’s increasingly hard to find filmmaking support in the U.S. and a lot of my work has been overseas. Anyhow, I’d always go to the Kunsthistorisches Museum and revisit their Bruegel room and I increasingly felt that those 16th-century paintings somehow echoed my own experience as a filmmaker. This related primarily to shooting in a documentary mode on the street, where there’s a kind of democracy of action, with random events and details all coexisting. You have to respond on the fly and construct your own narratives out of the great disorder. And then there was a lot of personal life and death stuff that fed into the film as well. The movie was brewing for a long, long time.

Keyframe: There is an interesting balance between naturalism and scripting here. In your director’s statement, you mention an interest combining the immediacy and openness of documentary with characters and invented stories. That ambition is readily apparent, and makes the film compelling. It seems as carefully composed as the paintings that appear in the film, yet also so comfortably wandering. What was the process of writing the script? And how involved were the actors?

Cohen: If one takes it apart, it is indeed a curious hybrid, though most who’ve seen it would agree that it feels like one of the most accessible things I’ve done. I didn’t write a locked, traditional script—I didn’t want to hand one out; I wrote script pages and voiceovers, notes and ideas, and then the film became a combination of carefully written segments coupled with improvisation. So the actors came up with some invaluable and funny material. But it was guided improvisation, where I explained that certain things had to be addressed but allowed for other things to arise in the moment. The long scene with the docent was actually tightly scripted in advance. Ela Piplits did an amazing job with the delivery, but she doesn’t have a background in art history that I know of. Overall, my goal was to confuse the line between what might be actual and ongoing and what is constructed for the film—not in order to be clever or ‘meta’ about it, but just so it feels rough-hewn and spontaneous, like life.

Keyframe: As it seems to be so much about wandering and observation, how much did the film evolve along the way?

Cohen: We generally didn’t lock off locations, so the actors had to be ready to slip into the ‘real’ world at a moment’s notice, and people from the real world were also sliding in and out of the shoot. We had to be ready at any time to whip the camera away from the primary scene or subject if something interesting sprang up—light, weather, passersby, something peripheral that might actually become central to the film. Some of the script evolves out of footage rather than the other way around. It’s hard to describe—like many filmmakers I’m a control freak, but I combine that with its opposite, putting a lot of faith in what the world will drop on the doorstep. I shared the interior camera work with Peter Roehsler, but carried a Super 16mm film camera to wander with outside on my own. I’m used to doing that kind of observational searching all the time anyhow.

Keyframe: What was your relationship to Vienna prior to making this film? And how did you gain access to film in the museum?

Cohen: The Viennale has kindly shown a lot of my work over the years, and eventually commissioned a live music-plus-film show (Evening’s Civil Twilight in Empires of Tin) that we did with Vic Chesnutt and a big band in 2007. Bobby Sommer, the lead in Museum Hours, did readings from Joseph Roth novels in that piece, and the project led me to explore Vienna, not that I needed much encouragement. I always want to poke around. As for the museum, the Viennale helped get the first meeting but we essentially gained access by asking. I explained at length to the administrators that I wanted to make a movie about why certain grand old institutions like theirs were, or should be, entirely relevant to regular people’s lives, and they responded well. They opened their doors with great generosity, but then we did our own thing. They didn’t vet the script or the completed film. We did agree to keep the production stripped down so as not to interfere with their operation—we used natural, existing light and generally shot while the museum remained open. I’m really thankful to them.

Keyframe: Similarly, what was your relationship to Bruegel’s paintings?

Cohen: I get a big kick out of Bruegel. I’m not obsessed, but he’s amazing in many ways—his genuine interest in the actuality of peasant life, of street life in general, coupled with forays into the fantastic… Most of my work is grounded in the everyday, which can also be very strange, so I would hope we somehow share common ground. He decoupled landscape from being just the background for religious subjects, and compared with most of his contemporaries he pulled large-scale oil painting down to earth, into the world we all move through. I see him as a radical force, but also humble and funny. My relationship felt personal; I somehow felt he was a proto-documentary filmmaker.

Keyframe: Would you talk about your process of casting? I was unfamiliar with Mary Margaret O’Hara—though tickled to learn that she’s Catherine O’Hara’s sister! What was the process of working with her—you note a degree of trust or an idea that she would flourish as a character in a foreign environment, which seemed to really pay off.

Cohen: I first saw her perform as a singer almost twenty five years ago and I’ve admired her immensely ever since. And she has a brief but spot-on role in Robert Frank and Rudy Wurlitzer’s Candy Mountain. There’s a life force that she embodies—brilliant, funny, unrestrained and wide-ranging. We’ve been in touch for many years, off and on, and I always wanted to film her. Also, she and Vic Chesnutt were friends and mutual fans—both one of kind, so she understood that his spirit was vital to this film. She’s been a very understanding viewer of other films I’ve made, no matter how unusual, and even though she sees a lot more ‘normal’ comedies and things than I do, she and I share a deep love for certain movies like Pasolini’s Gospel According to St. Matthew. She’s not known for taking the more mainstream path, and that was vital to this film. She worked hard, but she’s also very funny so it’s quite special to be around her. Everyone enjoyed her.

Keyframe: The point of view tilts between her character and Bobby’s. Can you say more about how you found him, and what bands he worked with back in the day?

Cohen: He worked as a tour manager towards the end of disco, in the early days of punk/new wave; I don’t even know the exact bands, but the details didn’t really matter; it was one of a string of odd jobs. Some of his life went directly into the film, which helped the performance feel natural, but some of it was just good, restrained acting. When I met Bobby, he was a driver and waiter, but he also spends a lot of time in China, so there’s a whole other layer of his life that we didn’t touch on.

Keyframe: I love the line spoken by the docent regarding how Bruegel’s paintings are ‘not sentimental, nor do they judge.’ Clearly that is the approach you take with your work. Could you say something about sentimentality?

Cohen: ‘Sentimental’ can be synonymous with ‘saccharine’ and that’s where they got the artificial sweetener. Movies tend to rely on the stuff all too often, and it’s very easy to access via overbearing soundtrack music, predictable narrative structure, overacting. We all want to chew bubblegum every once in a while but don’t mistake it for real food. However, some things that people might associate with sentimentality can actually be more complicated. Frank Capra tapped into real darkness in It’s a Wonderful Life, which helps it transcend the sentimental. Personally, I do try to steer away from sentimentality but I’m no cynic either. In fact, leaning on sentimentality as a way of increasing profits is where real cynicism lies. This interview is about an essentially friendly film that celebrates people helping each other out in times of trouble. One can do that without sentimentality.

Keyframe: You have done so much work related to music and the nomadic lifestyle that accompanies it. (Great to see Patti Smith’s producing credit in this one.) As the film is dedicated to Vic Chesnutt, there is a subtext about music and mortality (and the sense of immortality of the recording). Can you elaborate on how this theme grew within the project? Is it in the way that Mary’s character works in a bar, Bobby a former roadie?

Cohen: To be honest, I didn’t cast Mary intending for her to sing in the movie. I loved her presence as a performer, but also just as a person. The singing unfolded naturally—if someone had to spend a lot of time alone in a hospital sitting by an old friend—they just might sing to them, like you’d sing a lullaby to a kid. She says in the film that she works part-time in a bar, but we weren’t thinking of rock ‘n roll. I do draw a lot of personal history and inspiration from music and musicians. I love what they can pull out of thin air. Vic was a close friend for many, many years. I produced his North Star Deserter album and took the picture of him in a museum that’s on the cover of At the Cut. We talked about art as a kind of daily sustenance. There are people for whom art is just there—it’s like water or air to them; not a game, a career move, or a market. It offers communication, mystery, and kicks—in the deepest sense. I put Patti in this category, too. The fact that they, and Guy Picciotto, are all musicians is interesting—but I’m not even sure how directly it connects to this movie. It’s more that they’ve done a lot of intensely personal work outside of the mainstream, and also that music has been a big part of my life.

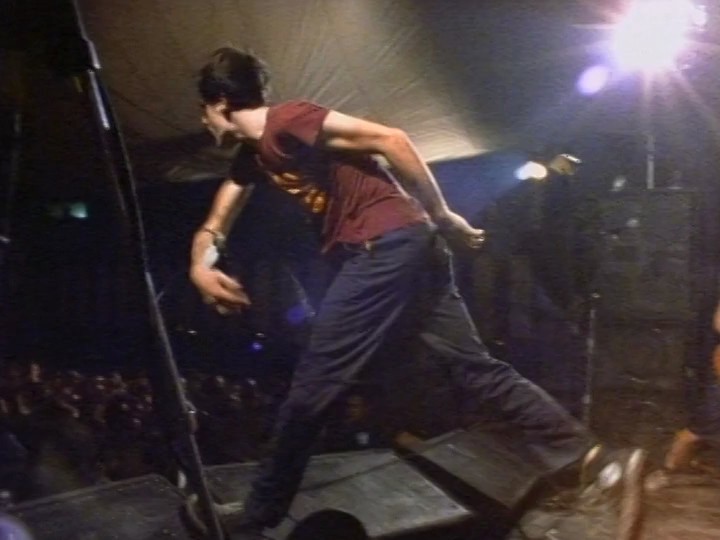

Keyframe: Instrument resonates with Museum Hours in its themes of landscape and uprooted-ness. Are you still in touch with Fugazi?

Cohen: I’m still friends with all of the members; Guy helped a lot with Museum Hours and we’ve collaborated on many other projects in the last years; Empires of Tin, We Have an Anchor, the Occupy Wall Street Newsreels, etc., but I’m also very close with Ian we go back over thirty years—and I’m good friends with Joe and Brendan. I’m doing a shooting gig for Brendan next week. Their lives have changed because they all have families and so are, by necessity, rooted. But they’re also still the hilarious fellows they always were; very unpretentious, politically concerned, and still making music in various bands and projects. I think we all share a deep curiosity and joy and horror in seeing how the world rolls forwards. And backwards.

Keyframe: Any thoughts about digital distribution venues?

Cohen: It depends what you mean, as digital distribution is taking many forms. At its worst, it can be pretty bleak—if the tech is bad, if people watch films at poor resolutions and wrong aspect ratios, or on a laptop or smart phone while simultaneously checking their email or Facebook, or if there are intrusive ads, or just in a brightly lit room…

It’s shocking how, overall, the experience of watching movies has in many ways degenerated in spite of (or because of) ‘technological progress.’ And I’m not thrilled about the bit-torrent bootlegging side of things, where people seem to feel entitled to be able to watch and ‘share’ everything instantly, whether or not the filmmaker has any say or will see any return that might help them keep making their work.

That said, sites oriented towards cinephiles can be pretty amazing—they’re making it possible to see rare and seminal films that may never be available in one’s town, and they could be instrumental in expanding a playing field that tends to get steamrolled by commercial mainstreaming. I do have to confess—I don’t watch a lot of digitally distributed feature films yet. I’m just too insanely busy trying to finish or archive my own work and trying to make a living, plus I still tend to want to see films big, in a darkened theater if I can. But I’m sure I’ll become much more involved, both as viewer and in terms of getting work out and around.

It is important to note that it shouldn’t be seen as a replacement for theatrical. Museum Hours has a distributor, Cinema Guild, and I think they’ve done incredible work in the past supporting unorthodox, important films and actually getting them into theaters. I am very happy to be working with them. And I’ve had great longterm relationships with small, primarily educational distributors like Video Data Bank, who’ve been in the trenches for years, arranging screenings at universities, media centers, micro-cinemas, etc. But they generally serve particular niches and aren’t there to aggregate the whole range and history of cinema. Digital distribution, like so many emergent aspects of Internet culture, is going to have to fight to keep its integrity in the face of many onslaughts, in particular the Internet model where ‘community’ and personal online interaction are really just tools for corporate, commercial gold-digging. Ideally, a digital distribution venue can and should be like a good museum—a place where the widest varieties of expression are cared for, curated, respectfully presented and discussed. So, for me, the main questions are: Can digital distribution maintain love of cinema as its core principle, and will it find fair ways to help truly independent filmmakers earn a living from their films so they can keep making them? I’d say the jury is out, but at least there are some promising signs.

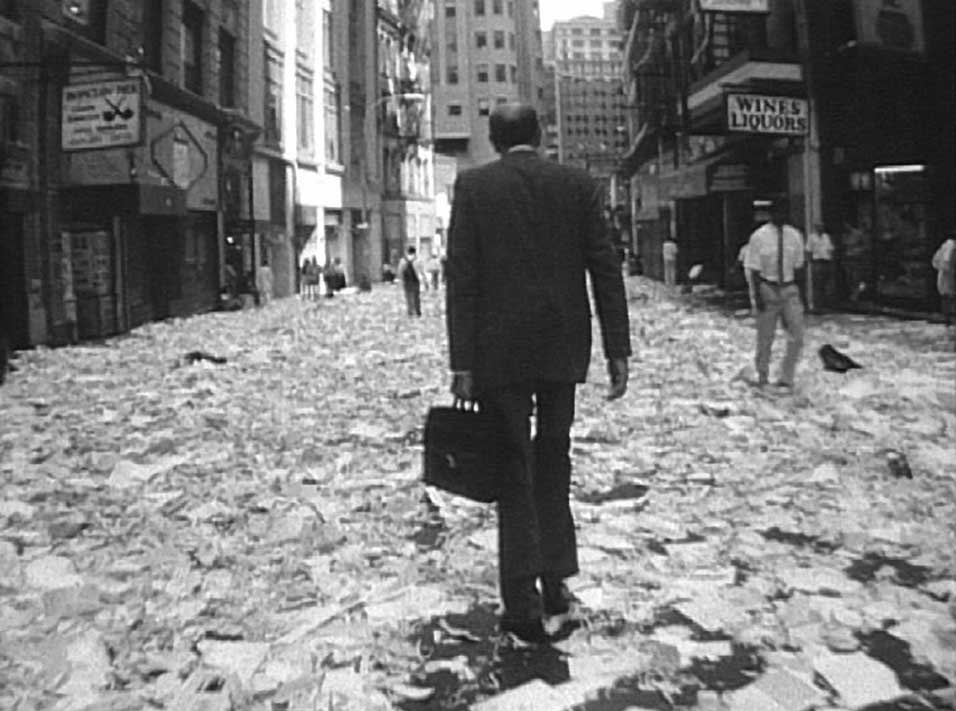

Keyframe: I was so taken with how Little Flags (2000) played in the September 11 exhibition at PS1. The prescience of the work is haunting. How do you feel your work plays in gallery contexts as opposed to screenings? The gallery is interesting to consider with Museum Hours which takes a more static, thoughtful approach to seeing objects and paintings than most films seem to.

Cohen: I’m interested in many different venues, as I damn well better be since most of my films have had to survive well outside of theaters and TV. I’m genuinely curious about different ways of presenting films, and different kinds of audiences. But I really want the tech to be good and for people to quiet down and concentrate so they at least have the chance to fully immerse. Venues need to respect the attention commitment inherently demanded for time-based work, and viewers need to allow work to unfold at its proper pace. I liked showing in that PS1/MoMA 9/11 exhibition because all kinds of reverberations were encouraged between many different forms of expression, and the film is short enough that it’s fine to show on a loop. I do like screening in museums, where the viewers tend to be more random than at galleries or movie theaters—you get locals, school groups, foreign tourists and, yes, guards.

Keyframe: Any upcoming projects?

Cohen: I’m always shooting, gathering, cutting. I have new shorts shot in the United Arab Emirates, Russia and Brooklyn. I’m making some films in response to the passing of Chris Marker. We Have an Anchor—a live music/film show is going up in New York as part of BAM’s Next Wave series. And I want to make more features, that’s for sure. There’s one I’ve been working on for twenty five years, about Times Square/42nd Street in the late eighties and early nineties. It’s the damn money/survival tar pit that makes it hard to get them done and out… but I’ll always have something coming down the pike.